IMAGE: A unintentional theme from the Headspace: Scent As Design conference – at least three different speakers used this random archival photo in their presentations.

In his book The Emperor of Scent, Chandler Burr describes the case of Janet Rippard, “a former nurse living in rather a remote part of Scotland.” Rippard was suffering from cacosmia, an olfactory disorder that causes sufferers to find all smells – even those of flowers, fresly-baked bread, or their favourite fragrance – utterly disgusting. She first noticed the disease’s onset while eating ginger biscuits with a friend:

I remember saying to my friend indignantly, “They’ve changed the recipe for these ginger biscuits! They taste like black treacle.” But they hadn’t changed the recipe. What was changing was me.

For the next five years, Rippard was tormented by the disgusting smells that surrounded her. A walk along the beach seemed more like a stroll through a sewage treatment plant, and everybody – including herself – stank. Smell is responsible for as much as ninety percent of a food’s flavour, so Rippard could hardly bear to eat. She lived, explains Burr, “on a diet of wholemeal bread, all-bran cereal, and boiled bleached rice.”

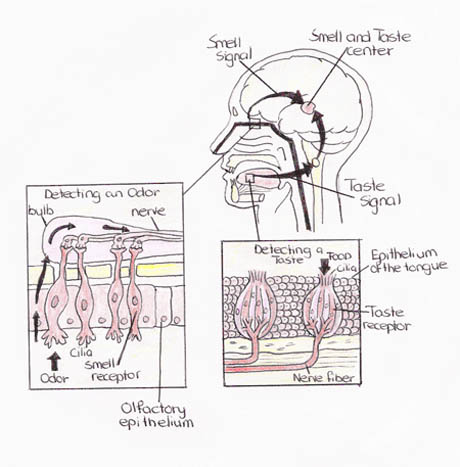

IMAGE: Anatomical sketch of human smell and flavour receptors, via. Amazingly, no one actually knows how human olfaction works.

Rippard was about to undergo surgery to sever her olfactory nerves altogether when she met Luca Turin, the hero of Burr’s book and the leading proponent of the vibrational theory of smell. To make a long story short, he cured her, and her sense of smell returned to normal. Incredibly, though, Rippard’s dramatic shift in scent perception was accompanied by a subtle recalibration in her experience of space. Burr describes the moment thus:

On a Saturday evening, December 16, Mrs. Rippard was sitting on her sofa when she suddenly wondered if there was something different about the room she was in. She would have sworn the actual dimensions of the walls were changing ever so slightly, an alteration in the geometry of the space around her, the objects in it, and their relationship to one another. Then she realised, with a jolt, that she was smelling normally.

I heard Burr re-tell this story on Friday, at Headspace, a day-long conference at The New School’s egg-shaped Tischman Auditorium. The conference’s premise was that scent is an under-used, but potentially revolutionary, design tool, and Burr’s anecdote served to illustrate that smell does indeed shape spatial perception at least as powerfully as light or sound, producing both form and atmosphere.

IMAGE: Fragrances from CB I Hate Perfume include the Scent of New Fallen Snow, In The Library, as well as At The Beach 1966.

The day was structured around a series of “Accidental Perfumer” sessions put together by the conference organisers (MoMA‘s Paola Antonelli; Seed CEO Adam Bly; Jamer Hunt, Director of the Transdisciplinary Design MFA at Parsons; Véronique Ferval of International Flavors and Fragrances, Inc.; Laetitia Wolff; Jane Nisselson; and Burr himself). These scent design experiments paired professional perfumers with product, furniture, and food designers, as well as an architect, with mixed but fascinating results that included grass-flavoured yoghurt and an anti-gravity fragrance.

The most ambitious “Accidental Perfumer” experiment, however, was L’Eau Vert du Bronx du Sur, the co-creation of Majora Carter, urban design and environmental justice activist, and Pascal Gaurin, creator of Tom Ford Black Violet and Vera Wang for Men.

IMAGE: Map of the South Bronx Greenway, a project spearheaded by Majora Carter to create bike & pedestrian paths around the Hunts Point and Port Morris waterfronts.

Carter began by framing the current smell of the South Bronx in terms of its environmental and economic challenges: the area handles forty percent of New York City’s waste, for example, and an estimated 3000 diesel lorries drive through the Hunt’s Point peninsula every day. Meanwhile, Guarin confessed that in French slang, “C’est le Bronx” means “It’s a mess.” Never one to think small, Carter asked Gaurin to create a new smell for the neighbourhood: something green and fresh, like the smell of the air after a big rain storm; something that would give everyone who smelled it a momentary lift.

IMAGE: The FEAR of smell – the SMELL of fear, by artist Sissel Tolaas, who used micro-encapsulation technology to embed cold sweat from the armpits of eight frightened men into paint, which was then applied to an art gallery wall, where it could be experienced by scratching and sniffing.

Gaurin confessed that the brief was difficult: normally, a perfumer aims to create something with broad, cross-demographic appeal that works on the scale of a human body. Carter was asking him to create something that would have an impact on an entire urban community, but was micro-locally specific in terms of its target audience. Still, he mixed orange flower extract and cis-3-Hexenol and a whole laundry list of other chemicals to arrive something leafy, green, and uplifting enough to satisfy Carter.

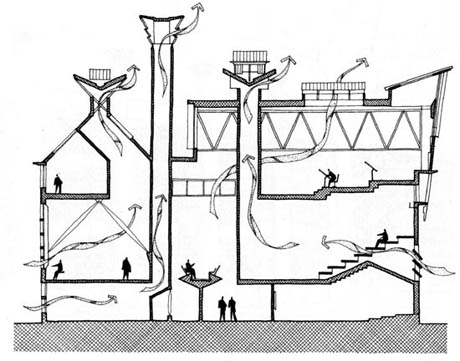

Carter and Gaurin then played with the idea of micro-encapsulating their scent in the pavement, where it would be released through footfall as a subtle encouragement towards physical activity. When the technical challenges proved insurmountable, they decided to use the perfume to scent an entire building in the South Bronx, by releasing it through the ventilation system.

IMAGE: Ventilation section, via.

Finally, in a process so surreal that, if I hadn’t seen the video footage, I’m not sure I would have believed it happened, Gaurin and Carter worked with the building’s janitor to release four or five different scents into the HVAC ducts, and get feedback from the residents.

The winning fragrance, L’Eau Vert du Bronx du Sur, was, according to Carter, “bright and light – the opposite of all the other smells in the neighbourhood,” while Gaurin described it as “the olfactory equivalent of a green roof.” On the other hand, Chandler Burr, as the discussion moderator, detested it, complaining that the orange flower made the scent smell like plastic and offering to come up to the Bronx with Carter and Gaurin in order to refine the fragrance before its further release.

IMAGE: Planting a green roof in the South Bronx, via.

The organisers had arranged to have Carter and Gaurin’s scent diffused through the auditorium during their conversation, which provided a visceral understanding of the problems entailed in scenting an entire building or district: many conference attendees muttered or tweeted that they felt sick or were getting a headache as the scent quickly became overwhelming in the stale air.

Still, the experiment drew attention to the idea that smell is a neglected aspect of urban design – a powerful tool for shaping spatial perception that is rarely factored into the planning and decision-making process.

The current smell of the South Bronx, as Majora Carter pointed out, is clearly a human artefact, from the zoning laws that permit waste handling stations to the freeways that encircle Hunt’s Point. The problem is that those urban planning decisions were made without consideration for the olfactory environment they were indirectly creating. In a way, then, the city agencies of 1970s New York were the real “Accidental Perfumers,” with Carter and Gaurin demonstrating, despite their project’s flaws, what a more intentional approach to urban smell design might look like.

IMAGE: Deodorant guns, via.

Meanwhile, in case L’Eau Vert du Bronx du Sur strikes you as a thought-provoking but ultimately entirely speculative and whimsical project, the very next day, The Guardian ran this headline: “Beijing to sweeten stench of rubbish crisis with giant deodorant guns.”

In the article, journalist Jonathan Watts reported that in response to complaints about the smell of Asuwei landfill site from local residents, Beijing officials are installing hundreds of “high-pressure scent guns, which can spray dozens of litres of fragrance per minute over a distance of up to 50m.” Incredibly, Watts adds that the deodorant guns are already in use at several other Chinese landfill sites, “as a temporary fix.” The rest of the article is well worth a read for an overview of China’s growing waste problem, but sadly offers no clues as to what sort of scent is used to mask the odour of the festering rubbish.

With New Delhi also currently installing a giant air freshener, Majora Carter and Pascal Gaurin’s South Bronx perfume suddenly seems to point the way towards the future of urban scent design research. The possibilities are endless – scent remediation, scent preservation, even scent augmentation – but the consequences are unknown – and, given our current state of olfactive illiteracy, are all but unimaginable.

[Thanks to Tim Maly (Quiet Babylon/@doingitwrong) for the deodorant gun link.]Discover more from Edible Geography

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

6 Comments

Hi Nicola,

Great blog! I love it! My colleague Kat and I are researchers in a UK business school investigating smell at work and have just finished a small study on employee experiences of smell in the workplace which we’ll publish the findings of on our blog later this summer.

Your review of the Headspace conference has given me lots of new leads an info, so thanks very much!

Sam

Landfills in the US have used deodorizers to mask unpleasant smells for decades- not a new strategy…

Splendid article, and lots of interesting links as well.

This reminds me of Alain Corbin’s wonderful book “The Foul and The Fragrant”, which links the history of odor and disgust to urban planning in 19th century Paris. (Patrick Süskind admittedly used much of the material for his Perfume novel.)

Which is to say that while scent may often be neglected in urban design, it has never been wholly absent. What’s obviously new here is the conscious & scaleable production of urban scents (instead of just avoiding or distributing the existing ones).

and btw to Georgia – Majora’s scent is not meant mask the bad smells, but motivate people in their homes to think bigger and go out to enjoy many of the new parks and trees that they may not be aware of or feel like getting out to because of an otherwise oppressive environemnt

actually, Majora outed the French for using “Le Bronx” to describe a “mess” – she said she learned this on her honeymoon trip to Paris. But it was all good – nice article.

Fascinating — you attend the most interesting events. Would like to smell L’Eau Vert du Bronx du Sur.

Am not sure that masking malodorous places is an environmentally progressive strategy…