The year I moved to New York, Sockerbit, a Scandinavian pick-and-mix sweet shop, opened in the West Village. I went once, and never again in the six years I lived in the city. The problem was not that I did not enjoy the fragrant, soft pink Smultronmatta (rippled squares of wild strawberry licorice) or the refreshingly tart Rabarberbitar (cylindrical rhubarb gummis with a lemon-flavoured filling); the problem was that I could not trust myself to exert any degree of self-control once across Sockerbit’s threshold.

IMAGE: Some of Sockerbit’s chewy delights, including Dansk Skalle, Rosa Kubik, Smultronmatta, Rabarberbitar, Super Sura Banana, Elefantskumfotter, and Rambo Twists.

As it turns out, this is a problem that the Swedish authorities, in all their benevolent wisdom, had anticipated. In her review of Bon Bon, a newly opened Swedish sweetshop on the Lower East side, Hannah Goldfield introduces the delightful concept of lördagsgodis, or Saturday Sweeties: a day of the week set aside for unbridled candy consumption, on the understanding that the other six will be gummi-free.

Speaking as my former self—a child who used to receive my pocket money on a Saturday morning, and hit the pick-and-mix aisle of Woolworth’s shortly thereafter—I can understand how this might work. Saturday Sweeties was the inadvertent outcome of the fact that I spent my money all at once and the sweets didn’t last much longer. But, Goldfield writes, in Sweden, this Saturday candyfest extends well into adulthood—indeed, it has been the official public health recommendation of the Swedish government since the 1950s.

The problem began in the 1900s, when sugar became affordable enough for manufactured candies to be mass-produced and widely available. By the 1930s, as sweet-makers introduced foam and jelly-textured offerings, the overwhelming majority of the Swedish population had cavities. Indeed, only one in a thousand military conscripts didn’t have tooth decay. In response, following the Second World War, the Swedish Parliament introduced a public dental service, but also commissioned a study, to be performed by the country’s only dental institute, in order to establish “what measures should be taken to decrease the frequency of the most common dental diseases in Sweden.”

At the time, scientists assumed that there was a link between diet and dental caries, but they were divided on whether tooth decay should be thought of holistically, as a symptom of deficiencies in overall nutrition, or locally, as the direct result of consuming sugar. It was quickly decided that the study should be carried out at the Vipeholm Institute, a state hospital “for individuals with mental handicaps,” situated just outside Lund. In an era before institutional review boards, the inability of the subjects to provide informed consent was, apparently, not an obstacle. The trial was also, controversially, supported in part by the country’s sugar industry and sweet and chocolate manufacturers.

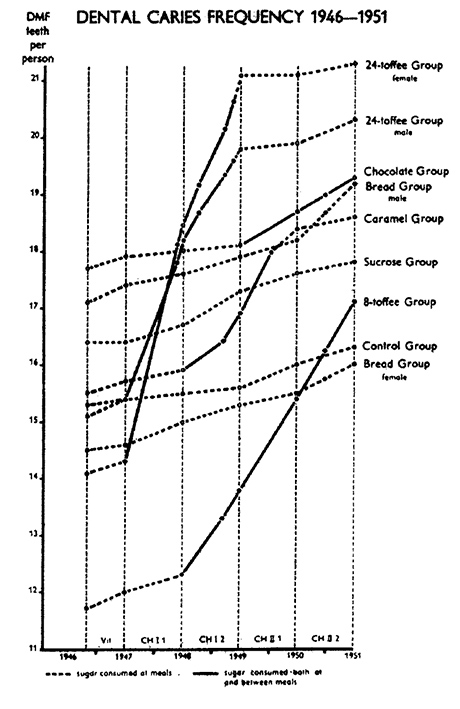

During the first part of the study, dentists studied the impact of vitamin supplementation on dental caries, and found no effect. In the next phase, they administered sugar in both sticky and unsticky forms. At mealtimes, patients might receive either a sucrose drink “with only a light retention tendency,” or “new bread”—a sticky, sugar-fortified bun. In between meals, they were served up to 24 pieces of “Vipeholmstoffee”—”very popular caramels,” specially formulated to last longer and be stickier than normal toffee.

The results were striking. Consuming the caramels between meals was associated with a significantly increased occurrence of tooth decay. The Swedish authorities promptly launched a campaign to limit sweet-eating occasions, suggesting that children should save their candy to eat while listening to a popular radio programme on Saturday evenings. The accompanying public health message translates as: “All the candy you want, but only once a week.”

IMAGE: Chart from “The Vipeholm Dental Caries Study: Recollections and Reflections 50 Years Later,” Bo Krasse, Journal of Dental Research, 2001.

Today, Goldfield reports, Swedes eat more candy per year per capita than the citizens of any other country, at more than 30 pounds each—but the rate of dental caries among twelve-year-old Swedish children, is, according to World Health Organisation data, “very low.” Sweden does not fluoridate its tap water or salt, but its youth still have a lower rate of decayed, missing, or filled teeth than those, say, in the United States. Of course, whether lördagsgodis, the provision of public dental care, or some other factor is behind that improvement is still to be determined.

According to a 2001 paper by Bo Krasse, one of the dentists involved, the Vipeholm Study had other, potentially more important outcomes. “We as dentists did not see any ethical problems with the study itself,” he writes, noting that most of the symptoms were only “early enamel lesions,” which re-mineralised when the toffee was withdrawn. Meanwhile, over the course of the six-year-study, the hospital’s chief physician concluded that “both the general and the mental health of the patients improved markedly.” Still, in 1953, when the study’s results were published, the resulting outcry prompted the Swedish government to forbid the future use of Vipeholm patients as research subjects. The study is still cited in medical ethics debates today, although Krasse seems unrepentant. “My reflection now,” Krasse concludes, “is that the Vipeholm Study illustrates two well-known sayings: (1) The end sometimes justifies the means, and (2) it is easy to be wise after the event.”