The first telegraph sent across the Atlantic, on 16 August, 1858, read: “Glory to God in the highest; on earth, peace and good will toward men.”

The contents of the first transatlantic telephone call, placed by AT&T President Walter S. Gifford on 7 January, 1927, were more mundane: a report the next day in The Manchester Guardian noted that the weather and the time difference were the main topics of conversation, and that “a more pleasantly futile dialogue could hardly have taken place over a suburban party-wall in Dulwich or Chorlton-cum-Hardy.”

IMAGE: Walter S. Gifford places the first commercial trans-Atlantic telephone call. Photograph: AP via The Guardian.

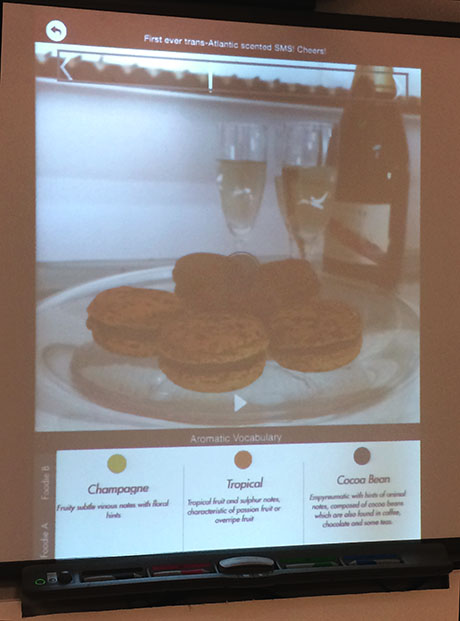

Yesterday, at the transmission of the first transatlantic smell message, perfumer Christophe Laudamiel sent an olfactory snapshot from Paris to New York City, and a small but eager audience at the American Museum of Natural History were treated to the scent of champagne and macarons.

“Nibbled in Paris, tasted in New York!” Laudamiel said, as he hit send.

IMAGE: The first transatlantic smell message, projected for the audience at the American Museum of Natural History. Photograph: Nicola Twilley.

IMAGE: The oPhone was designed to resemble an abstract, minimalist flower planter in order to help users feel comfortable smelling it, according to Vapor Communication’s co-founder, Rachel Field. Photograph: Nicola Twilley.

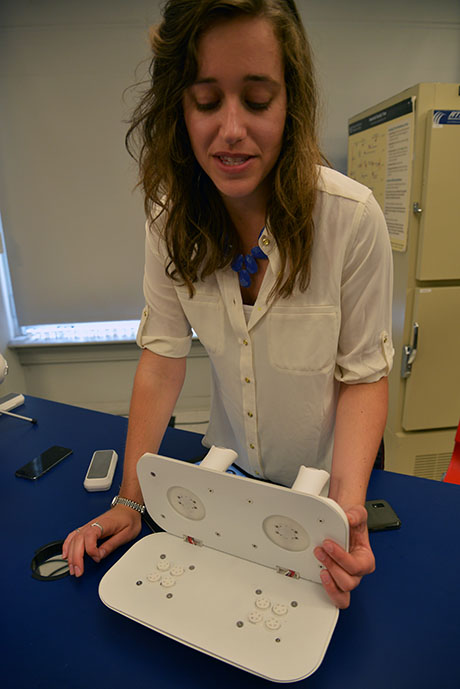

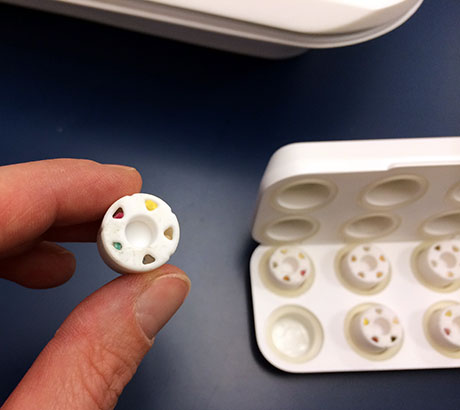

The event was a launch of sorts for Vapor Communications’ first product, the oPhone Duo, a small, brick-shaped device mounted with two smell delivery tubes. The oPhone is required to “play” a smell message: it reads the tagged scents beamed from the message recipient’s iPhone using Bluetooth, swivels the correct odour cartridge slots into place, and then blows a ten-second burst of air through the chunks of solid perfume, up to your nose.

The experience is a considerable improvement on earlier Smell-o-vision experiments in that the scents are delivered to a single recipient, in a short burst, with no more than three different smells in combination per tube. The reasoning behind this is that it takes humans about three to four seconds after exposure to detect a scent, and about ten seconds after that to reach saturation, or olfactory fatigue — the point at which the epithelium is overwhelmed enough to be temporarily unable to distinguish new aroma molecules.

Meanwhile, researchers have also found that ordinary, untrained humans can typically pick out only three or four different notes within a smell — more than that, and the brain lumps them all together as a single smell.

“In a way,” says David Edwards, the Harvard professor who co-founded Vapor Communications with his former student, Rachel Field, “the nose was made for olfactory tweets.”

IMAGE: David Edwards holds an odour cartridge, or oChip. Photograph: Nicola Twilley.

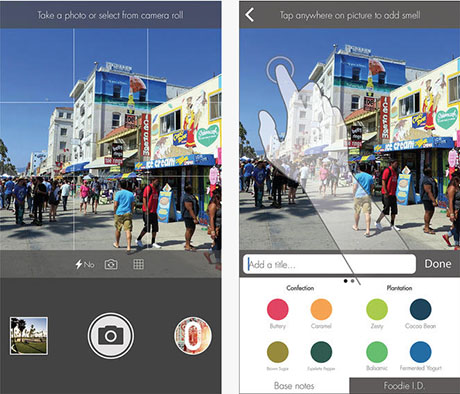

For now, anyone with an iPhone and a Facebook account (which counts me out, disappointingly) can compose and send a smell message: you simply download the free oSnap app, take a photograph, and tag it with up to two sets of up to four smell tags each.

IMAGE: Screenshots from the oSnap app.

These are chosen from a pre-existing range of thirty-two food-related aromas organised into five palettes, from “Paris Afternoon” (“tomatoey,” “meaty,” “onionish,” and “red wine.”) to “Confections” (“buttery,” “caramel,” “brown sugar,” and “espelette pepper”).

IMAGE: The system currently offers thirty-two food-related aromas organised into five palettes. According to Rachel Field, “tomatoey” was the trickiest smell to get right, as it was much more potent at a lower concentration than the other odours in its group.

The resulting smell is an abstraction of an abstraction: a croissant and coffee might become a jet of “buttery” “grilled toast” accompanied by a “zesty” “cacao plume.” If the sender is equipped with an oPhone themselves, they can test and tweak their smell message before sending it, adding “bitter cocoa bean” or “yeasty brioche” notes as necessary to match their real-world aroma experience as closely as possible.

Imagining a generation of oSnap users repeatedly trying to distill their own aroma experience in terms of these pre-assembled scent “phonemes” raises the interesting question of how this new, albeit limited, olfactory language, complete with associated colours, might end up re-shaping odour and flavour perception.

In studies, the descriptors used on menus or food labels have been shown to exert a huge influence on what flavours consumers subsequently report experiencing. It’s easily to imagine a similar effect by which an oSnapper will perceive croissants as more buttery and toast-like, and less floury, say, or sweet, than someone who is not trying to summarise the aroma using Vapor Communications’ limited palette.

It’s even possible that the oSnap app might even induce a new synaesthesia, in which chocolate is associated with purple and onions “taste” turquoise.

IMAGE: Rachel Field allows members of the audience to experience the first transatlantic smell message on the oPhone. Photograph: Nicola Twilley.

Of course, as Edwards speculated, it’s entirely possible that in the future the app could use image-matching technology to mine a database for aromas associated with the thing you’ve just taken a picture of, so that the user doesn’t have to rely on their own perception (this, of course, risks reduction to an olfactory average: all glasses of red wine will smell the same in scent message form).

Vapor Communications is also developing an oPhone “Uno,” which will attach directly to your phone, trading portability for a reduced palette of aromas. Edwards also mentioned discussions with car companies, to deliver coffee aromas to sleepy drivers.

For right now, however, eager early adopters can reserve their own oPhone Duo as part of an Indiegogo campaign, but will have to wait to experience their smell messages (or oNotes, as the company calls them) at a handful of public oPhone “hot spots” (the American Museum of Natural History will host one, starting in July).

The slow roll-out has a silver lining — Edwards and his colleagues are using it to understand how people actually use scent messaging in the wild. Thus far, for example, they’ve been surprised to see more non-food than food-related oNotes. In the forty-eight hours the app has been live, users have already created “Lady Gaga,” “My Room,” and “Smoky Beach” — a hint that Vapor should probably move beyond what they call “foodie adventures” in future oPhone cartridges.

(For those who are worried about being pranked by unkind friends sending fart smell messages: it’s possible but not easy. Rachel Field told me that the team has developed a “barf” cartridge, filled with four particularly disgusting odours, but that those aromas are not yet publicly available through the oNote system. And, because the receiver would have to intentionally load their oPhone with the barf cartridge, anyone who was subjected to a fart message would have had to have set themselves up for it ahead of time: no nasty surprises here.)

IMAGE: Rachel displays the interior of the oPhone Duo, including the cartridge slots. Photograph: Nicola Twilley.

IMAGE: Edwards and Field worked with perfumers and flavorists to encapsulate custom-blended aromas in solid matter to fill the cartridges. Field estimated that the odours in a cartridge would last a month in regular use. Photograph: Nicola Twilley.

With only thirty-two base aromas, yielding a maximum of 300,000 combinations, the oPhone/oSnap/oNote olfactory ecosystem is still frustratingly limited and awkward to use right now. And, frankly, I’d have been more excited if Edwards and Field had chosen to use individual aroma molecules over pre-made analogues — Isoamyl acetate rather than banana, for example, or cis-3-Hexenal instead of freshly cut grass — so that users could start to understand real-world smells as the sum of their chemical constituents.

Still, I’ve ordered my oPhone Duo. And when I’m old and grey, and the sending and receiving of long-distance sniff-o-grams is just a normal part of everyday life, I’m sure I’ll tell everyone who will listen that I was there to smell the first transatlantic scent message in the world…

Thanks to the inimitable Paola Antonelli for alerting me to the event.

Discover more from Edible Geography

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

4 Comments

As someone who is hypersensitive to scents, I greet this news with horror. I already get a vicious headache from a wide range of perfumes & such. Depending on the ingredients in the scent cartridge, this could be very cool … or incredibly, hot-poker-through-my-temple painful.

The second message sent by the trans-Atlantic telegraph was “Go to Chicago.” This was the first paid message, and it cost $5 to send. The sender, interestingly, was John Cash of J & J Cash, a ribbon maker who later developed the first printed name labels, like the ones in kids’ clothing at summer camps. The receiver was his New York sales rep.

The scents transmission idea sounds like a fun novelty, but not something I’d be interested in. I’m a big champagne fan, and Piper Heidsieck does not smell like Charles Heidsieck which does not smell like Jacques Chaput. I’d love to be able to use my iPhone to record odors, replay them and even transmit them, but they’d have to be the kinds of odors I’m interested in. If I’m working my way through the House of Caron, I’d want to send the appropriate scents, not approximations.

OH MY GOODNESS!!’ This is absolutely the first I’m hearing about this! And you’re right, it is a little crude but this is absolutely going to be a normal part of life in a few decades. I wasn’t going to comment before but none of my friends get why this is so cool and awesome. I needed somewhere to express my excitement Loll

Fascinating post, Nicola. And I’m happy that you addressed the very real concerns of receiving fart smells over one’s o-phone. Looks like Frat Foodies will have to resort to more traditional methods of pranking their bros.