IMAGE: Graf Zeppelin, USC Digital Archive, California Historical Society: TICOR/Pierce, CHS-8436.

While researching Zeppelins — the enormous hydrogen-filled airships invented in Germany at the end of the nineteenth century and used to bomb Britain during the First World War — Cambridge University engineer Dr. Hugh Hunt stumbled across their little-known culinary implications. As The Guardian puts it:

With the guts from more than 250,000 cows needed to produce the bags that held the hydrogen gas in each Zeppelin, the German war machine had to choose between long-range bombing and wurst. It chose the former.

The result was a ban on sausage-making in Germany and German-occupied territories. A report on balloon fabrics, prepared by Captain L. Chollet for the U.S. National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics in 1992, described the collection of cow guts during the war as “very systematic.”

Each butcher was required to deliver the ones from the animals he killed. Agents exercised strict control in Austria, Poland and northern France, where it was forbidden to make sausages.

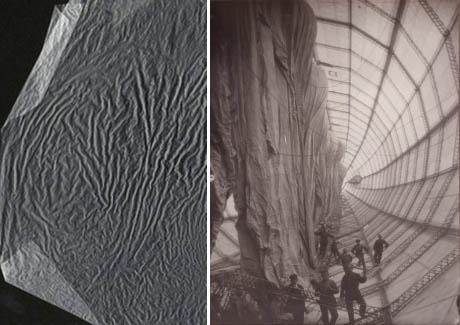

IMAGE: Beef casings, via.

Instead of encasing seasoned pork, the cow’s intestines were carefully separated out, washed, and the outer membrane peeled away. A contemporary book conservator attempting to recreate the process today noted the olfactory unpleasantness of the job, warning that he “would recommend to anyone wanting to duplicate this work, that they lay in a supply of clove oil or Lysol spray disinfectant as well as a good tight-fitting mask with fresh filters.”

After being washed in alkaline solution and stretched dry, the resulting parchment-like material is called “goldbeater’s skin,” because it was traditionally used to sandwich a sheet of gold in order to beat it down to gold leaf, just 1 micron thin.

IMAGE: (left) Goldbeaters’ skin. Image courtesy of Talas bookbinders’ and conservation supplies, New York, via the V&A online journal. (right) From the building of the airship “Bodensee” in 1919. The empty gas bags are hanging from the frame in the hull of the airship. Photo: Archiv der Luftschiff-bau Zeppelin GmbH. Via Post & Tele Museum.

Although the German government experimented with fashioning airship gasbags from rubberised materials, they could not make the seal between sheets tight enough to contain hydrogen atoms (the lightest element in the world, with only one particle).

Meanwhile, sheets of goldbeater’s skin, if overlaid and wetted, fuse together as they dry. The resulting fabric is all but impermeable: Chollet’s technical report claims that the German goldbeater gasbags, had, “for a weight of 130 to 150 g per sq. m, a tightness permitting the loss of only a few litres of hydrogen per sq. m in 24 hours, under a pressure of 30 mm of water.”

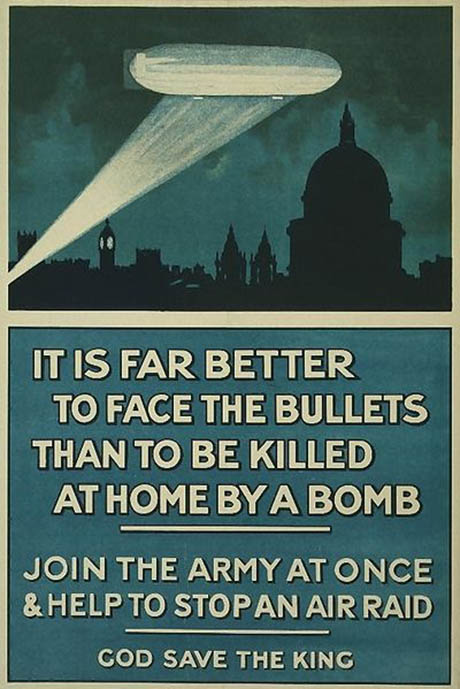

IMAGE: World War I recruitment poster showing a Zeppelin above London, via the Library of Congress.

Each silvery ship floating through the air represented up to 33 million potential sausage casings, sacrificed to the Kaiser’s nationalist cause. And thus the dawn of aerial bombardment — and, with it, the contemporary model of total war — was dependent on a sausage-free civilian diet, in one of the more unusual examples of the militarisation of food.

Earlier on Edible Geography, “War on Truffles.”Discover more from Edible Geography

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

4 Comments

If sausages were banned in Germany during WW1 because the the cow guts used to make sausages were needed in airship production, what happened to the sausage meat? How was it prepared?

I know that burgers were first invented in the US around 1850 or so. But, could the ban have resulted in sausage meat regularly being cooked as a patty and the burger becoming much more popular asa result ?

Thanks Davina! Fixed.

Very interesting article! Please just note that it is “conservator”, not “conservationist”!!!

What a treat to have found your website. I am enjoying the well written articles and plan to be a loyal reader !