IMAGE: A bomb crater in a rice field in Vietnam, photo via.

The impact of military manoeuvres on the agricultural landscape is often not positive, from the herbicidal ravages of Agent Orange to the truffle-decimating trenches of Picardy. Bombs, mines, and other explosive munitions carve new three-dimensional spaces into the landscape, digging holes in perfectly graded fields and demolishing buildings in densely packed cities.

In Europe, many of these battle scars have been more or less erased: filled in and reabsorbed into the environmental fabric, visible only through tell-tale shadows on satellite imagery or side-by-side comparison with old city views. Some still exist, either as deliberately preserved holes in the ground or as ad-hoc ponds (which, in turn, have formed inadvertent aquatic nature reserves).

IMAGE: Lochnagar Crater, photo by Richard Dunning. Lochnagar is a crater created on the first day of the Battle of the Somme and bought by Dunning to ensure it would be preserved rather than filled in.

IMAGE: This small round pond in the Hackney Marshes was created by a World War II bomb. Satellite view via Google Earth.

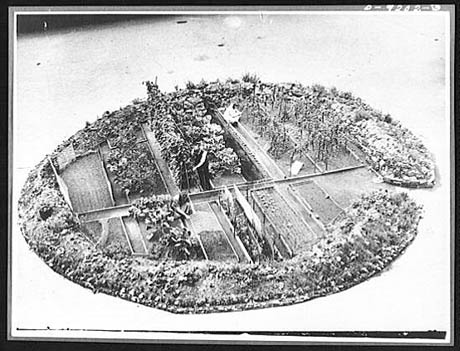

Recently, fellow Future Plural site Pruned has curated some examples of more productive uses of bomb sites, or what we might call crater cultivation. During the Second World War, for example, a Mr. Haynes planted and tended this tidy victory garden in a bomb crater near Westminster Cathedral.

IMAGE: Bomb crater victory garden (sadly long gone) near Westminster Cathedral, image from Pathé Films footage via City Farmer News.

IMAGE: Bomb crater victory garden, photo courtesy the Imperial War Museum, via Pruned.

During the Vietnam War, the United States dropped three times as many bombs on the Vietcong as were dropped anywhere during all of World War II. Indeed, Pruned writes that Xiengkhouang Province in Laos, after being on the receiving end of more than 580,000 bombing raids over nine years, or the equivalent of “one bombing mission every eight minutes around the clock,” is “considered the most heavily bombed place on earth.”

The result is a landscape pockmarked with craters and littered with bomb debris, as well as unexploded ordnance, which still kills several hundred Laotians each year. Some of the craters are dry, others have filled up with a combination of groundwater and rainwater to create what Pruned calls “an aberrant hydrology of micro-lakes.”

IMAGE: Photo of bomb crater ponds in Vietnam by Carsten Peter for National Geographic, via Pruned

One of the craters was turned into a kidney-shaped swimming pool by the future President of Laos (Pruned has photos). Of particular interest to Edible Geographers, however, is the way that both the bomb casings and the craters themselves have been made to yield an alternative harvest, in an ingenious replacement of the rice fields they otherwise disrupt.

According to journalist Ben Hills, locals in Xiengkhouang Province eat a lot of swallows, which they net when the birds fly into the dry bomb craters for a dust-bath. They also use bomb casings to “support rice granaries, form fences, and make pig-troughs and planter-boxes.”

IMAGE: A 61-metre-wide dry bomb crater in Laos, photo by Ross Lee Tabak.

IMAGE: Bomb casing planter in Laos, photo by Ross Lee Tabak.

Perhaps most intriguing are the craters that have become fish farms. Writing for Places [pdf], Thomas Campanella observes that in next-door Vietnam:

Bomb craters are favored sites for houses, with a replenishable source of protein at the doorstep. These relics have become part of the agrarian landscape, transformed from a symbol of death into one of life.

IMAGE: Mr. Mee’s bomb crater fish hatchery “in the uplands near the Ho Chi Minh Trail,” photo from Rural Aquaculture, via Pruned.