IMAGE: Mutatoes by Uli Westphal.

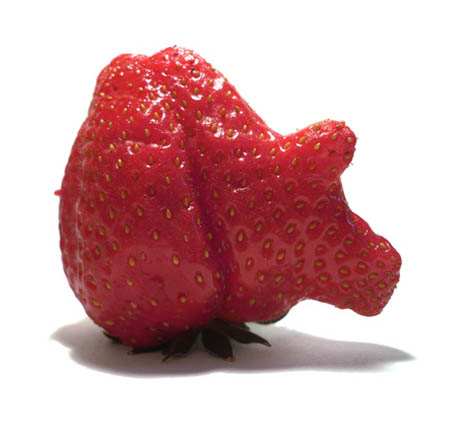

Since 2006, artist Uli Westphal has been collecting, documenting, and eating Berlin’s Mutatoes—the non-standard fruits, roots, and vegetables that can be found at the city’s farmers’ markets. His photographs form an archive of “these last survivors of agricultural diversity,” revealing an incredible variety of colours, curves, and contours.

IMAGE: Mutatoes by Uli Westphal.

For Westphal, these Mutatoes bear witness to “the suppression of mutation and polymorphism in our industrial food system.”

The complete absence of botanical anomalies in our supermarkets has caused us to regard the consistency of produce presented there as natural. Produce has become a highly designed, monotonous product. We have forgotten, and in many cases never experienced, the way fruits, roots, and vegetables can actually look (and taste).

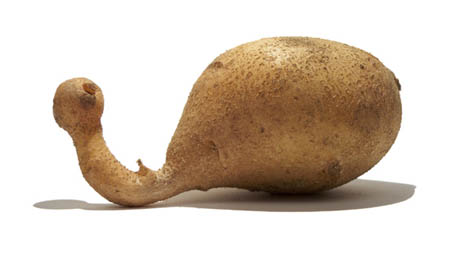

I first came across Westphal’s photographs thanks to a reader comment on “The Fruit Standard,” a post I wrote on the one-year anniversary of the partial repeal of the European Union’s fruit and vegetable standards.

The European Economic Community (the EU’s precursor) was set up in 1958 to create a common market, and one of the first issues to be addressed was the need for shared produce grading standards, to facilitate cross-border trade and guarantee consumer quality. Twenty-six fruits and vegetables were subject to “uniform standardisation parameters,” which prescribed that, to be recognised as such, “cucumbers must not bend at a gradient of more than 1/10, an onion could ‘only be sold if two thirds is covered in skin,’ and the white part of the leek had to ‘represent at least one-third of the total length or half the sheathed part.'”

IMAGE: Commission Regulation (EEC) No 1677/88, laying down quality standards for cucumbers, from Journeys, ed. Giovanna Borasi.

As I wrote in 2009, the rules, however well-intentioned, were a disaster in practice, resulting in one-fifth of fruit and vegetables harvested in the EU being discarded and destroyed, unable even to be given away. Nonetheless, national marketing standards provide a charming illustration of the methodological assumptions and absurdities of classification.

In their own way, the EU standards are a masterpiece of natural history writing: an extended initiative by Europe’s finest legal minds to define, through its range of permissible deviation, the ur-cucumber. What better way to know a strawberry than by the moments at which it becomes not a strawberry?

IMAGE: Mutatoes by Uli Westphal.

The other interesting thing, of course, is that EU bureaucrats and USDA officials alike measure whether cucumbers are cucumbers based purely on visual qualities — appearance and form — rather than taste.

This raises a larger question about how we perceive food. Although human taste and smell evolved to evaluate our edible environment, our sensory cognition and attendant quantification and classification systems are largely dominated by sight.

In fact, various studies have demonstrated the ways in which taste perception can be distorted by visual cues, with professional wine critics led astray by drops of Mega Purple in a Chardonnay and diners sickened when their steak was revealed to be dyed blue. No matter how deformed Westphal’s tomatoes are, cut up in a salad, they would undoubtedly taste as much (or more) like a tomato as their spherical supermarket peers. But, if served whole, would their irregular shapes, colours, and textures affect our perception of their taste?

IMAGE: Mutatoes by Uli Westphal.

Meanwhile, Westphal’s use of a visual medium, photography, and an identical, clinical white backdrop to present each strawberry or potato as an equal and individual example of its genre forces us to reconsider the very idea of evaluating fruits and vegetables. How should we define and grade food? And what do the standards we consciously or unconsciously impose on produce tell us about ourselves, particularly given the fact that today’s fruit and vegetables are a human-designed artifact, the result of centuries of domestication and breeding.

Today, only those varieties capable of providing high yields, consistent symmetry, and the resilience to emerge relatively unscathed after traveling through global supply chains are grown commercially. Even Westphal’s most deviant cucumbers are all from the same eight modern varieties bred to reduce bitterness and increase size:

At a certain point I started to realize that it is not only the natural occurrence of morphological irregularities in the growth of single plant varieties that is being suppressed and filtered out by the industrial food system. In fact, only a tiny fraction of high yielding, good looking varieties are being grown and distributed today, even though there are literally thousands of varieties of any domesticated fruit or vegetable.

Since the green revolution agriculture has experienced a mass extinction. A vast majority of plant varieties that humans have bred over the past 10,000 years has vanished within the last 50 years. The ever increasing amount of processed foods and food imports also contributed to the illusion that the diversity of our food supply was increasing, not declining.

The qualities by which we assess our fruits and vegetables, whether encoded in EU standards or simply in the purchasing choices of supermarkets, thus serve as an implicit guide to the landscape of industrial food, with its agricultural intensification, monocultural cultivation, and extended supply chains.

But the perfect, regular fruit and vegetables in our supermarkets also tell us as much about our shared aesthetic ideals as, for example, an art museum or beauty pageant. In his book, Mutants, Armand Marie Leroi writes about the diverse spectrum of human form (we are each, on average, born with three hundred genetic “mutations”) and our species preference for symmetry, and concludes that, perhaps, “the true meaning of beauty is the relative absence of genetic error.”

IMAGE: Mutatoes by Uli Westphal.

That may be, but I can’t help but hope that Westphal’s photos will help us extend our appreciation for the formal inventiveness of fallible plant life.

[NOTE:Thanks to Ramona Ranchera for the introduction to Uli Westphal’s work, and PSFK for the reminder. For more on similar subjects, check out these earlier posts: “The Fruit Standard” and “The Opposite of a Vegetable”.]