The logical offspring of two recent food trends – gastro-tourism and heirloom fruit and veg – is clearly vegetable tourism. After all, if people will travel to Melton Mowbray for an authentic pork pie and pay extra for a Brandywine tomato, why not make a pilgrimage to the site where “one of the fastest growing and earliest-harvesting of all peas,” the Prince Albert, was first bred and grown? Or the nursery where Kirke’s Blue plum (“juicy flesh and a free stone”) was raised in the 1820s?

IMAGE: Vintage seed packet, from London’s lovely Garden Museum. According to Forgotten Fruits by Christopher Stocks, the Ailsa Craig is named after “an uncanny looking island of the Scottish coast,” which could, “with a little imagination, be said to bear a passing resemblance to a submerged onion of titanic size.” The island is “composed of a fine granite that provided the material for most of the world’s curling stones” and is now home to about 70,000 gannets.

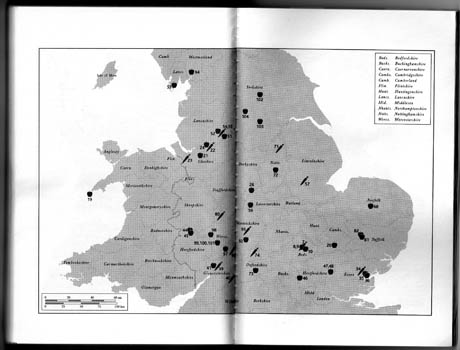

The would-be vegetable tourist could do worse than start with Christopher Stocks’ Forgotten Fruits, a hugely enjoyable (re)introduction to the most important or interesting of Britain’s traditional and forgotten fruit and vegetable varieties. Tucked into the appendices is a map and gazetteer, “in the cause of stimulating local pride, as well as offering some intriguing destinations for a most enjoyable pilgrimage.”

IMAGE: A Vegetable Gazetteer of the British Isles (from Christopher Stocks’ Forgotten Fruits)

The social, agricultural, and geographical history woven into just a brief introduction to Vaux’s Self-Folding lettuce or the Bedford Fillbasket brussels sprout is incredible.

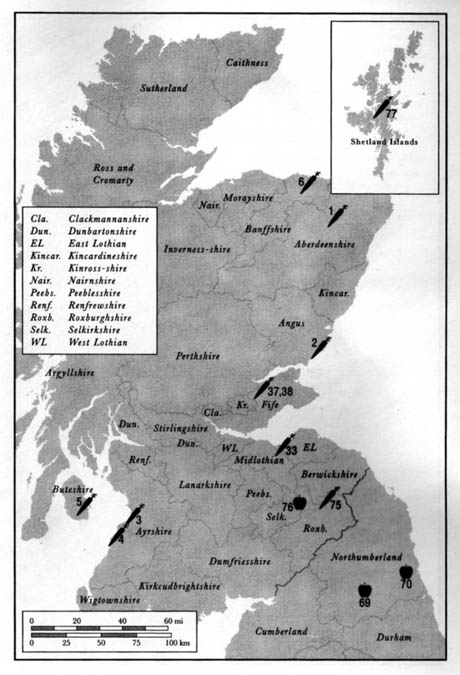

Stocks’ suggested sites in Scotland, for example, would take the vegetable tourist from the Isle of Arran, where Donald Mackelvie bred the purple-skinned Arran Victory, to the Arbroath home of the Golden Wonder, a chance mutation discovered in a field of Maincrop by John Brown in 1906, and raw ingredient of the original ready-salted crisp.

Along the way, Stocks’ intrepid tourist would encounter William Sim, who abandoned potatoes in favour of emigration and carnations (his is still the best-selling carnation variety in America), as well as the Scottish Potato Bubble of 1900-04, fuelled in part by Archibald Findlay of Fife, a grocer’s son and breeder of optimistically named varieties such as Eldorado and Millionmaker.

IMAGE: A Vegetable Gazetteer of the British Isles (from Christopher Stocks’ Forgotten Fruits)

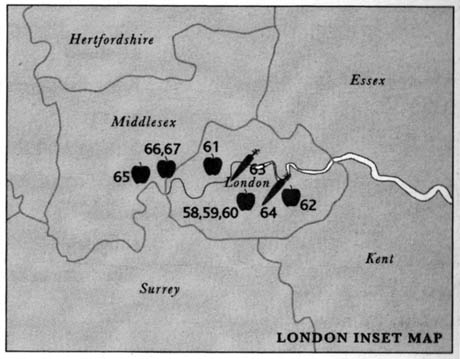

IMAGE: Detail map, from the Vegetable Gazetteer of the British Isles (from Christopher Stocks’ Forgotten Fruits). In Brixton, we find (58), (59), and (60), sites associated with the Prince Albert rhubarb, Victoria plum, and Victoria rhubarb. Brompton is home to (61), Kirke’s blue plum, while Lewisham’s claim to vegetable fame is (62), Hawkes’ Champagne rhubarb. Still south of the river, (63), James’s Longkeeping onion, is from Lower Marsh, Waterloo, while New Cross is the origin of (64), the Prince Albert pea.

Of course, the sceptic might be wondering what there actually is to see on the Scottish potato trail – and perhaps even speculating as to whether this kind of tourism might be more suited to the armchair adventurer. Speaking as one of the latter, I can confirm that Stocks’ series of gooseberry biographies and celery vignettes is perfectly suited for consumption as paperback non-fiction.

In fact, I’d go as far as to say that vegetable writing is up there with wine label descriptions in the underappreciated micro-literature stakes, whether consumed in book form, or encountered on supermarket labels, seed packets, or the Heirloom Gazetteer™ iPhone app of the future.

IMAGE: A pride of potatoes. Photo from the Garden Museum‘s fascinating archive of gardening images.

Many of the stops on Stocks’ sightseeing itinerary have the potential to be somewhat underwhelming, given his descriptions. The original home of Cox’s Orange Pippin, which accounts for more than half of the dessert apples grown in the UK, is now underneath a “deeply uninspiring block of modern low-rise flats,” “sandwiched between Heathrow airport, the Queen Mother reservoir, and the M25.”

Meanwhile in Markinch, Scotland, the achievements of potato entrepreneur and pub landlord Archibald Findlay, father of the Up to Date and British Queen as well as the previously mentioned Eldorado and Millionmaker, have only recently been marked by a plaque outside the Chinese restaurant that replaced his Portland Bar.

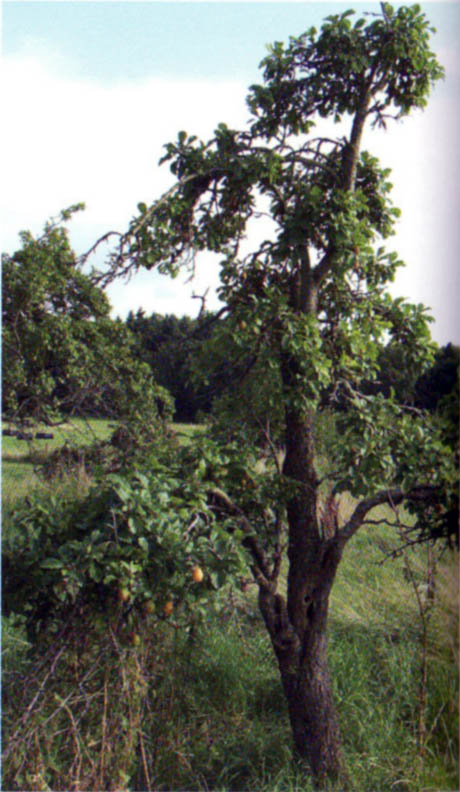

Other varietals have been more fortunate. The Pershore Yellow Egg plum (“excellent for cooking and jam, if too dry to be pleasant eaten raw”) was first “discovered growing wild in Tiddesley Wood, just outside Pershore in Worcestershire, by a local man called George Crook.” Not only does Tiddesley Wood still survive, but the Yellow Egg still grows there, looked after by the Worcestershire Wildlife Trust.

IMAGE: A Pershore Yellow Egg growing in Tiddesley Wood, Worcestershire. Photo from Christopher Stocks’ Forgotten Fruits).

Meanwhile, the original Bramley’s Seedling apple tree, which accounts for up to ninety percent of all cookers sold in Britain, is still growing in Southwell, Nottinghamshire. According to Christopher Stocks, “around 1900, it blew over in a storm and the present tree grew up from a toppled branch.” What’s more, on its 200th anniversary in 2009, this venerable grandfather of so many apple crumbles, dumplings, and pies was succesfully cloned by scientists at the University of Nottingham.

Clearly, the fates of significant fruit and vegetable heritage sites have varied. Stocks’ quotes H. V. Taylor, a fruit expert writing in 1948:

The breeders of the new plums seem to have less sentiment for plums than for apples, for whilst pilgrimages are made to see the original trees of Beauty of Bath, Ribston Pippin, Bramley’s Seedling, Newton Wonder, etc., no attempt was made to preserve the original trees of important plum varieties…

Today, as Stocks points out, the origins of the Beauty of Bath have become obscure, while the orchard behind the Hardinge Arms, where the Newton Wonder apple tree was first cultivated by another publican, William Taylor, was chopped down to build new houses in 2004.

The practice of vegetable tourism, then, is perhaps less about the chance to enjoy unspoilt countryside or pick-your-own heritage vegetables, as much as a crusade to revive traditional varietals and the stories attached to them.

It is also a question of which histories we value. After all, there are blue plaques all over London, marking the houses where celebrated writers, artists, and statesmen lived or worked – but there is no sign to mark the site of Joseph Kirke’s nursery, former home of Kirke’s Blue, now buried under the Victoria & Albert Museum. As Stocks concludes:

It would be a fairly safe (if possibly contentious) bet that Cox’s Orange Pippin, say, has given more pleasure to more people over the years than the works of William Wordsworth, and is probably known to more people too. But while Wordsworth’s homes in Grasmere, Ryadal, and Cockermouth have been preserved for posterity, the house and garden where Richard Cox lived were swept away long ago…

IMAGE: The original Bramley’s Seedling tree. Photo courtesy Joan Morgan.

Taste and biodiversity value aside, the origins of these heirloom fruit and vegetables are signposts to a lost geography – vanished market gardens that still send up the odd radish or strawberry, or stray plum varieties, presumed lost until rediscovered in the back gardens and parks of Devon villages.

As Stocks’ guide and gazetteer makes clear, forgotten fruit and vegetables can tell us as much, if not more, about all kinds of changes in British society, land use, and diet over time, than their successful cousins. The stories that lie behind the development, naming, and distribution of different fruit and vegetable varietals are a form of archaeobotanical evidence, testifying to the impact of the railways, the economics of fruit storage, or the efforts and achievements of individual plant hunters and breeders.

January’s perhaps not the best season, but why not visit an Orange Jelly turnip (Chester) or Telephone pea (Thorp Perrow, North Yorkshire) soon?

Fantastic post. I’ve also noticed that both underutilized, word-of-mouth plants and romanticized heirlooms actually leave clues to terrain, which lead to interesting hypotheses. A recent interview with a local about a lost local aromatic plant revealed thorny and non-thorny varieties, whosee distribution I suspect correspond to a popular cattle route because of response to disturbance. Accounts of more leathery leaves may also reveal adaptation lost streams and rivers, which were never mapped.

Now, with this whole place paved over, I’m not sure if this quest of mine still matters, but, having led to finding the only remaining hidden rice field (with a water buffalo, to boot) in this city, it is certainly interesting to myself.

Here in the tropical periurban jungle, where many things were never named or never written on a piece of paper, and the terrain itself is bursting with diversity and changing all the time, I wish to dream tonight of some kind of basis for this kind of tour.

It’s brilliant because there is so little these days that is unique to a specific place (Starbucks is everywhere after all), you can almost get anything you want anywhere in the world. Vegetable tourism on the other hand brings back a sense of uniqueness to travel. I love it.