A couple of weeks ago, Berlusconi mouthpiece Il Giornale ran an article alleging that Naples’ pizza ovens are fuelled by “wood from coffins dug up in the local cemetery”:

Pizza, one of the few symbols of Naples that endures… is hit by the concrete suspicion that it could be baked with wood from coffins. Not only the pizza, the bread, too, may have been cooked with the wood.

Veteran mafia prosecutor Giovandomenico Lepore is leading an investigation into the practice, in which gangs dig up caskets and sell them on to “hard-hearted” and/or “cost-cutting” bakery and pizzeria proprietors for use as firewood.

Apparently, cemetery theft is rampant in Naples, with 5,000 flowers vases “snatched in broad daylight” from local graveyards last year. There is, however, no word on whether the coffin wood is oak, as specified in the Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana‘s guidelines for making authentic Neopolitan pizza.

IMAGES: Return to Sender artisan eco-casket by Greg Holdsworth.

I was reminded of this story during a visit to the Cooper Hewitt’s National Design Triennial, Why Design Now?, last week. Among the innovations on display was a Return to Sender artisan eco-casket by New Zealand designer, Greg Holdsworth.

At the funeral of his father-in-law, who had been a wood-working enthusiast, Holdsworth was horrified to see that the coffin was made of formaldehyde-filled MDF with a plastic woodgrain and plastic handles applied to the exterior. His subsequent research showed that most Western caskets are made of similarly unsustainable and non-biodegradable materials, turning cemeteries into “parking lots” for the dead, as Cynthia Beal of the Natural Burial Company puts it.

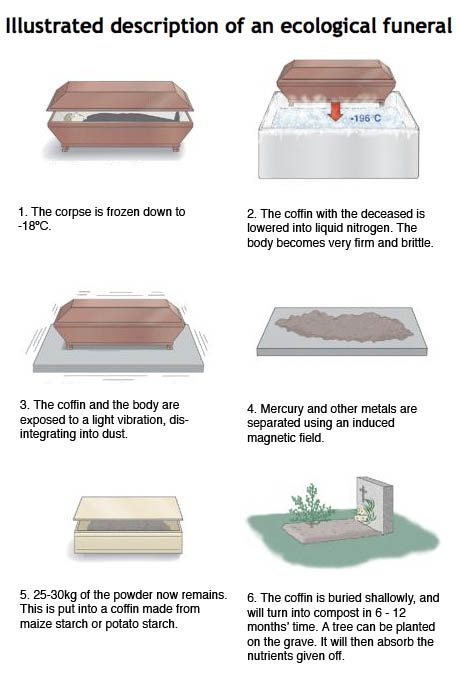

Although perhaps not perfect pizza-oven fuel, Holdsworth’s design is a simple, lightly-oiled plywood casket deliberately designed to break down in the soil. Other eco-burial methods go further, embedding seeds in a paper coffin, creating artificial reefs from cremated ashes, or using a combination of liquid nitrogen and high-frequency vibrations to compost your corpse.

IMAGE: Illustrated description of the human-composting method of eco-burial, via Promessa.

Of course, turning dead bodies into worm food is standard in many parts of the world, long before its current growth in popularity in the West. For a long time, however, Western (and particularly Christian) burial practices have been defined by attempts to keep the body intact and ready for resurrection. One of the more mysterious and quixotic efforts to avoid the decomposition and re-absorption of our ancestors is documented in David Wilson’s wonderful film, ОЪЩЕЕ ДЕЛО, or The Common Task.

IMAGE: Nikolai Federov Federovich by Leonid Pasternak, via Wikipedia.

A co-production of the Museum of Jurassic Technology and Kabinet, The Common Task narrates the story of Nikolai Fedorov Fedorovich — “his unusual origins, his modest life, and remarkable thought.” Hypnotically strange, the film conjurs up a pleasurable if slightly melancholy state of mystical suspended reality that is the hallmark of MJT productions.

As the voice-over relates, Nikolia Fedorov Fedorovich was “born in 1838 in south central Russia,” and, despite being “modest in the extreme and in all aspects of his life,” and never finishing his degree due to “an undisclosed incident,” he “became one of the most influential thinkers in Russia — not only for his, but for all time.”

Nikolai Fedorovich Fedorov had but one vast idea, one thought, one realisation from which the whole body of his work was to spring and that idea was that all problems known to man have a single root in the existence of death. […] Accordingly, Fedorov clearly proposed a single task towards which all efforts of human kind should be directed — a common task for all mankind — the single undertaking to which all living humans should be devotedly engaged: the universal physical resurrection and resurrection of all who have gone before but are no longer living.

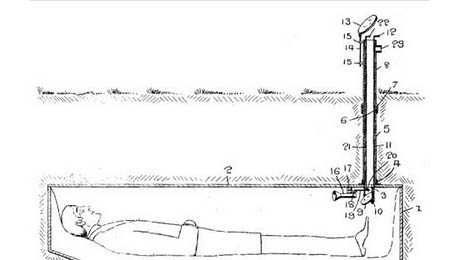

IMAGE: A drawing from the patent issued to George Willems of Roanoke, Illinois, in 1908, for a coffin-mounted periscope that could be used to “ensure the entombed person was still dead,” and presumably monitor their state of decay, via.

Under the title “The Question of Sanitation,” Fedorov explored a major obstacle to universal resurrection, namely that “our need to eat to stay alive has caused us as a species to feed ourselves on the bodies of our forefathers. As the disintegrated bodies of our ancestors are returned to the earth and through the earth to the crops we eat, our bodies are nourished by those who have gone before.”

The solution, as Fedorov saw it, was to remove all risk of consuming ancestral dust by “resynthesizing our own bodies so that they no longer require nourishment from organic matter.”

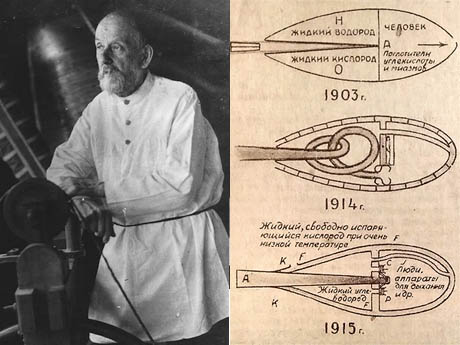

IMAGE: Konstantin Tsiolkovsky and some of his sketches for “lighter than air” ships, via and via. Tsiolkovsky, the stone-deaf father of Russian rocket science, also features in The Common Task, as Nikolai Federov’s “most ardent adherent.”

Sadly, Fedorov appears to have made little progress in this area, although his writings also advocate activities to enhance crop yields (to feed more people from fewer ancestors) through agricultural collectivisation, the elimination of wars, and artificial rainfall. The Common Task also traces the influence of Fedorov’s thinking on extra-terrestrial exploration through the founding of the Soviet space program. This formed an important consequence of his plans, because “as preceding generations are resurrected, the earth will overpopulate, and accordingly, man will have to look to the stars for our homes.”

IMAGE: Prahlad Jani, via and via.

As a side note, Federov’s resynthesis has perhaps been achieved by an Indian fakir with a soft palate deformation. According to the BBC, Prahlad Jani is in his eighties and claims not to have eaten or drunk anything for several decades — a boast that appeared to be substantiated during a ten-day stay in a laboratory in 2003, during which time he consumed nothing, but remained in good health.

IMAGE: Model food dishes for the afterlife, Shaanxi province, China , Ming dynasty, about AD 1450–1600, courtesy of the British Museum. The dishes form a “feast for the soul in the afterlife,” and consist of “five main meats (a goat, a pig, a rabbit, a fish, and a goose) and five accompanying dishes (pomegranates, peaches, water chestnuts, persimmons, and mantou [steamed bread]).”

Immortality, resurrection, fasting, and coffins: it seems that food frequently plays as important and varied a role in the afterlife as it does during life itself.

Nicky, you might also like to read about the utterly bizarre self-mummifying monks of Japan, if you haven’t already.

From Wikipedia:

“For 1,000 days (a little less than three years) the priests would eat a special diet consisting only of nuts and seeds, while taking part in a regimen of rigorous physical activity that stripped them of their body fat. They then ate only bark and roots for another thousand days and began drinking a poisonous tea made from the sap of the Urushi tree, normally used to lacquer bowls. This caused vomiting and a rapid loss of bodily fluids, and most importantly, it made the body too poisonous to be eaten by maggots. Finally, a self-mummifying monk would lock himself in a stone tomb barely larger than his body, where he would not move from the lotus position. His only connection to the outside world was an air tube and a bell. Each day he rang a bell to let those outside know that he was still alive. When the bell stopped ringing, the tube was removed and the tomb sealed. After the tomb was sealed, the other monks in the temple would wait another 1,000 days, and open the tomb to see if the mummification was successful. If the monk had been successfully mummified, they were immediately seen as a Buddha and put in the temple for viewing. Usually, though, there was just a decomposed body. Although they weren’t viewed as a true Buddha if they weren’t mummified, they were still admired and revered for their dedication and spirit.”

Do you really believe the fakir story?

That Fakir story is such utter bullshit. Humans have to eat, full stop.

Convenient how he was allowed “mouthwash”.