Lunch may be the second meal of the day today, but it was the last of the three daily meals to rise above its snack origins to achieve that status.

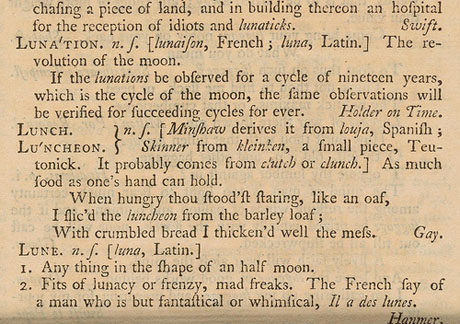

IMAGE: “Lunch” entry in A Dictionary of the English Language, Samuel Johnson, London: J. and P. Knapton; J. and T. Longman, 1755. NYPL, Rare Book Division.

As late as 1755, according to Samuel Johnson’s definition, lunch was simply “as much food as one’s hand can hold” — which, as Laura Shapiro, culinary historian and co-curator of the New York Public Library’s new Lunch Hour NYC exhibition, recently explained to me, “means that it’s still sort of a snack that you can have at any time of the day.”

And it wasn’t until later still — around 1850 — that lunch became a regular fixture between breakfast and dinner, added Rebecca Federman, the exhibition’s co-curator, Culinary Collections Librarian at the NYPL, author of Cooked Books, and a star panelist at Foodprint NYC.

Finally, by the turn of the century, “lunch was taking place between 12 and 2, more or less,” concludes Shapiro. It was a real meal at last, with a time associated with it, and particular foods and places assigned to it.

IMAGE: Lunch venue with a deli counter, silver gelatin print, 1942. NYPL, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division.

Those foods and places — the shifting cultural and spatial geography of lunch — form the meat of the library’s new exhibition, which opens today and runs until mid-February at the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building on Fifth Avenue & 42nd Street.

But the context for the entire project, which has been nearly two years in the making, lies in the fact that lunch is an urban invention — it is a former snack that only became the day’s third fixed meal as society urbanised and industrialised, and workers were unable to return home for dinner (always the main meal of the day) until late at night. As Shapiro explained:

Lunch came into its own — it really acquired the size and shape and substance that it has in America today — in New York. New York is emblematic, arguably, of large North American manufacturing cities — it has all the conditions that make America different from the Old World in terms of speed and work and the arrangement of life. In New York, the focus of people’s lives is work, and lunch is the meal that was just made to fit into the industrial, urban work day.

Although my adventures with Venue mean that I can’t be in New York for the exhibition’s opening, Shapiro and Federman were kind enough to sit down with me to discuss its themes and highlights, including a quick but fascinating digression into the lost world of ladylike peanut butter sandwich recipes, before I left town. You can read highlights of our discussion, which covers women’s lunching liberation, soda fountain slang, and the horror of salad, below, alongside photographs of the exhibition’s artifacts and installation.

IMAGE: Metal lunchboxes from the 1950s line the wall in this section of the exhibition. Photograph by Jonathan Blanc for the New York Public Library.

• • •

The Technology of Lunch: Sliced Bread and the Automat

Laura Shapiro: Sliced wrapped bread first appeared in 1930, and that became the sandwich standard right away. They had the slicing technology before then, but they didn’t have the wrapping technology and the two had to go together.

Before sliced bread, the lunch literature is full of advice on social distinctions and the thickness of bread in sandwiches. You slice it very thick and you leave the crusts on if you’re giving them to workers, but for ladies, it should be extremely, extremely thin. Women’s magazines actually published directions on how to get your bread slices thin enough for a ladies lunch. You butter the cut side of the loaf first, and then slice as close to the butter as you possibly can.

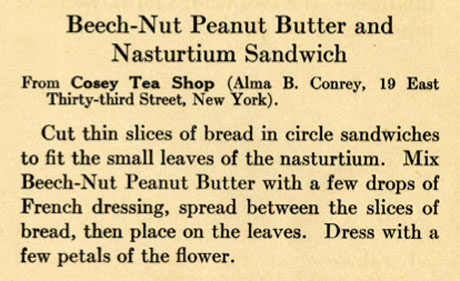

IMAGE: Cover of Beech-Nut Peanut Butter: The Great Tea and Luncheon Delicacy as Served in New York recipe book, published in 1914, and available as a PDF here.

Edible Geography: Were there buttering instructions too?

Shapiro: Certainly — butter had to go all the way to the edges, and so on. But the interesting thing is peanut butter, which was introduced as a high-end spread for bread. Even though it was cheap, it had a kind of ladylike aura about it, and so ladies’ lunches would feature perfectly sliced, hair-thin bread, spread with butter and crushed peanut butter — you would grind your own peanuts and mix them with something to make it more spreadable. Peanut butter and celery, peanut butter club, peanut butter salad — even peanut butter and nasturtium!

Rebecca Federman: I have a friend who still has peanut butter with butter. It’s good.

Shapiro: Jelly didn’t come later, until peanut butter filtered down to become children’s food — and then that was it. The ladylike recipes, with nasturtiums and so on, disappear completely.

IMAGE: Recipe for a peanut butter and nasturtium sandwich, from Beech-Nut Peanut Butter: The Great Tea and Luncheon Delicacy as Served in New York.

IMAGE: An Automat installed at the New York Public Library for the exhibition, alongside Berenice Abbott’s ”Automat, 977 Eighth Avenue, Manhattan,” from 1936. The first American Automat opened in Philadelphia in 1902, but quickly became an icon of New York City when it arrived ten years later. Photograph by Jonathan Blanc for the New York Public Library.

Edible Geography: Leaving ladies’ luncheons aside, lunch is set apart by being the first meal that is regularly eaten outside of the house, right?

Shapiro: Exactly, which meant it needed to be not only a low-cost and fast meal, but also reliably clean and high quality. All of those elements led to standardisation and automation. We have a display of the soda fountain slang — all of the drugstore lunch counters and soda fountains developed a special shorthand and insider lingo, which they would yell back and forth to communicate with each other. Jello was called “nervous pudding” — that was my favourite.

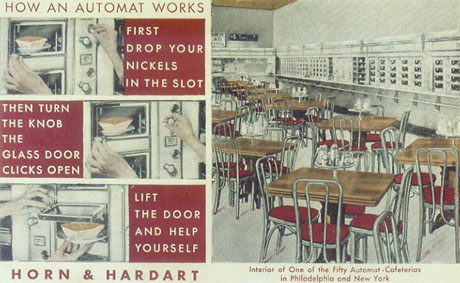

IMAGE: Automat instructions, via The Atlantic.

Federman: Then we have an Automat — a real one, restored to working order by Andy Pastore. The library actually has an amazing collection of Horn & Hardart Automat papers thanks to Robert F. Byrnes, who was an executive there for his whole career. No other single restaurant organization, certainly not in New York, has a collection to match that. It is the archive that all restaurants should look at, because they should all be doing this.

It’s organized by location, and within each location’s folder, by date. If they changed the sign, or if they put in a revolving door, they took a picture. They took pictures of the inside with people, so you see how people were eating, what they were wearing, whether they were sitting alone, and so on. They took pictures of the outside, so you get the street scenes. And then there are recipes!

IMAGE: A Horn & Hardart Automat in 1965, photographed by Neil Boenzi for The New York Times.

Shapiro: Every Horn & Hardart location had a manager’s book, with the rules for doing every single thing — how to squeeze the orange juice, how much filling to put on each sandwich, how to treat your customers, and how often to throw out the coffee. All the food came from a central commissary, which was a block-large building on 50th Street, between 10th and 11th. They did nearly everything there, for economy of scale and for quality control, and then they had extremely precise instructions for anything that had to be made in store. The idea was that any Automat you went to, you would get precisely the same dish.

Federman: And you never saw the people preparing your food, which somehow made it seem more sanitary, as if strangers weren’t touching your lunch. In the exhibition, we show the mechanics, so you can peek backstage and see how it worked.

IMAGE: The back of the restored Automat, installed at the New York Public Library’s Lunch Hour NYC exhibition. Photograph by Jonathan Blanc for the New York Public Library.

• • •

Defining Lunch: the Hot, the Hand-Held, and the Hungry

Edible Geography: For the purposes of the exhibition, how do you actually define lunch?

Federman: Drawing the line between street food, snacks, and lunch is tricky. We start the exhibition with a look at the varying definitions of “lunch,” and the early Samuel Johnson category of hand-held food. We have a hot-dog cart, an oyster cart, and a pretzel cart.

IMAGE: Street food installation, including a hot-dog cart on loan from Worksman Cycles. Photograph by Jonathan Blanc for the New York Public Library.

Shapiro: The street foods that go way back, like hot dogs and pizza, have never changed. It was lunch one hundred years ago, and it’s still lunch today. But, with waves of immigration, you see new lunch foods, so we have a small thing on Jamaican beef patties as one of the most recent lunch standards. The Jamaican beef patty shows up after 1965, after new immigration laws mean that more and more Caribbeans are coming to the city. Five minutes later, historically speaking, they’re everywhere — they’re in Grand Central Station, they’re in the school lunch program, and they’re an icon of New York.

IMAGE: Oysters were once the iconic street food of New York City, but over-consumption, pollution, and harbour dredging dramatically reduced their supply and priced them up into the fancy food category. Photograph of Lunch Hour NYC installation by Jonathan Blanc for the New York Public Library.

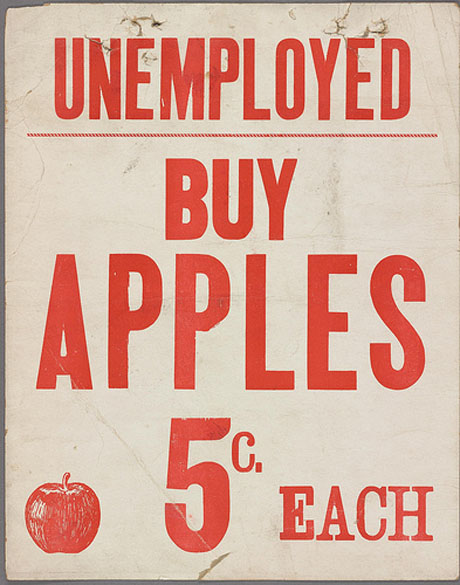

Federman: We also have these wonderful posters that people would display when they were selling apples during the Depression. For some people, especially then, an apple was lunch. The whole program was a huge mistake, but these apple sellers on the streets of New York became one of the lasting images of the Depression. The International Apple Shippers’ Association concocted the plan to get rid of a surplus of apples from the West Coast, but the market quickly became saturated, and then the surplus ran out and the price went up, and, meanwhile, the apple sellers no longer counted as unemployed for official purposes.

Shapiro: And there were so many complaints about apple cores in the streets.

Federman: I have no idea how these posters ended up in the library’s collection — I’d guess that some librarian just collected them off the streets. The exhibition is really made up of these kinds of pieces of ephemera — magazines and newspapers and clippings that document aspects of everyday life that aren’t necessarily documented elsewhere.

IMAGE: Placard advertising apple selling by the Depression-era unemployed, 1930. NYPL, Rare Book Division.

Shapiro: There are very few lunch cookbooks. There might be a section with luncheon menus, but you rarely see a lunch recipe. Instead, you see advice: this is good for lunch, bring this to a picnic lunch, the leftovers from this will make a good lunch, and so on.

The midday meal at home, because it was only for women and children, was especially overlooked. In the domesticity literature, you even see reminders not to neglect lunch, and to have more than a bite, catch-as-catch-can, because it’s important to keep up your strength for the day.

Federman: Finding what people actually eat everyday is almost always a challenge. In the exhibition, we have a couple of interviews with recent immigrants about how their lunches have changed since coming to this country. One of the people who was interviewed came from Tunisia and for him, lunch used to mean something warm. He has a hard time with lunch here.

Shapiro: He talks about salad with absolute horror!

IMAGE: A Heinz soup dispenser, a common feature of the soda fountain or luncheonette. Photograph of Lunch Hour NYC installation by Jonathan Blanc for the New York Public Library.

Edible Geography: My own grandmother was of the firm belief that a nice hot soup was the best thing for lunch.

Shapiro: It was once a common idea here, that every meal should have one hot thing, to be a meal rather than a snack. You see it in ads from the 50s — the Campbell company would put out the suggestion that soup should be the one hot thing, even in summer.

• • •

Luncheon Etiquette: At-Risk Hats and Unescorted Women

Edible Geography: As a set of lunch venues emerged — the cafeteria or quick-lunch restaurant, the Automat, and even the street — were they accompanied by a lunch etiquette that differed from acceptable behaviour at breakfast and dinner?

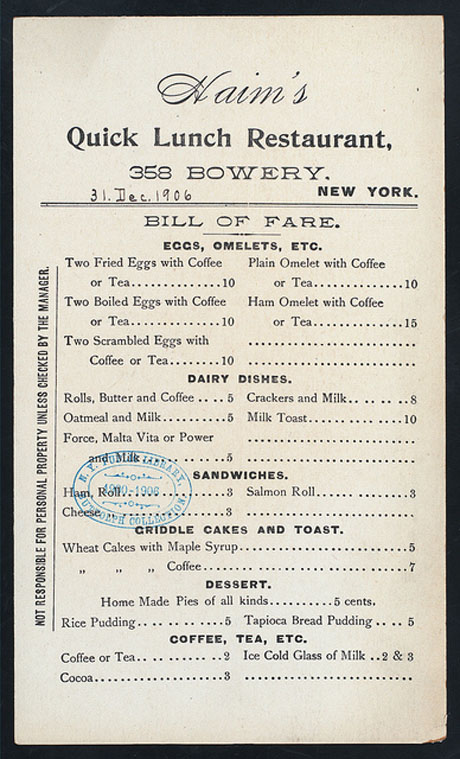

Federman: Speed is the defining characteristic of New York lunch etiquette. People from other countries always noted the speed at which the people of New York ate. At the quick-lunch places, it was understood that you got in and got out as fast as you could and the normal rules were thrown out of the window. You can see that in illustrations from the time, and you can even get a sense from the menus, which deliberately say things like, “We are not responsible for your personal property.” You could drop your hat on a chair to save it while you got your food, but if someone else sat down faster than you, all bets were off. It was every luncher for him or herself.

IMAGE: Haim’s Quick-Lunch Restaurant menu. New York, 1906. NYPL, Rare Book Division.

Shapiro: Which is why, as women office workers came to be part of the crowd, the cafeterias were seen to be too busy and bustling for them. That’s when you got things like Schrafft’s — slightly nicer places that developed very feminine identities.

Actually, the first women’s club in America began meeting over lunch in New York in 1868. They met at Delmonico’s because, like most fancy restaurants at the time, Delmonico’s did not allow women in unescorted for lunch. So they just walked in and sat down, and that was the start of the womens’ club movement. It wasn’t the suffrage movement by a long shot, but it was an example of women standing up for themselves and expanding their lives.

They liberated Delmonico’s in 1868, but it took 101 years before they liberated the Plaza Hotel. In 1969, Betty Friedan led a group of women to lunch in the Oak Room at the Plaza, where they still did not serve women who were not escorted by men. They sat there for two hours and the waiters wouldn’t go near them. The Plaza changed their policy within a few months, but they would not serve Betty Friedan that day.

• • •

Lunch Power: Nutrition and Networking

IMAGE: Charitable Lunch. Photograph of Lunch Hour NYC installation by Jonathan Blanc for the New York Public Library.

Edible Geography: The provision of school lunch is an enormous topic, as well as a controversial one. Do you touch on that at all in the exhibition?

Federman: We do — we have a timeline that comes all the way up to the present moment, from the start of the New York school lunch program, which began in 1908, through to today. A charity organization started it — the New York School Lunch Committee — out of concern at tenement conditions and seeing kids coming to school malnourished, underweight, and pale. Their lunch wasn’t free, but for three cents, you could get soup or macaroni and a piece of bread, followed by a sweet cracker or fruit or something like that. It started in two schools in the city and expanded over time, and after about twelve years, it became part of the Board of Education.

IMAGE: Boys eating at P.S. 40, Jessie Tarbox Beals. Silver gelatin print, 1919. NYPL, Manuscripts and Archives Division.

Shapiro: Everybody was worried about underweight as a form of malnutrition a hundred years ago, and now it’s the exact opposite. It’s still malnutrition, it just takes a different form as the country has changed.

Federman: We also have a small section on the Brooklyn Navy Yard cafeteria, which was opened by Anne Tracy Morgan, who was J. P. Morgan’s daughter and a big philanthropist. She felt that by opening a cafeteria on site, the Brooklyn Navy Yards workers would get more nutritious meals than they would get outside or if they brought them from home. They hired all these quick-lunch workers from the city who knew how to feed large numbers of people very quickly, but it wasn’t terribly successful — it closed within a year or two. I think part of it had to do with the fact that they didn’t serve any beer.

Shapiro: Speaking of J. P. Morgan, we also have a section on the “power lunch,” which, while it has existed wherever men in suits have gathered on an expense account, gained its name here in New York in the seventies.

IMAGE: Lunch at the Four Seasons, photograph by Susan Stava. Courtesy of the Four Seasons, via New York Magazine.

Federman: And, of course, there’s a whole geography of power lunches — both the particular restaurants to be seen at, and then, within the dining room, where power players would sit.

Shapiro: One of the things we do in the exhibition is define power more broadly — it’s not always the guys in the suits. New York, as a city, is full of different power circles for different interest groups that derive a lot of their strength from association. So, for instance, we also have a section on the writers and theater people who gathered at the Algonquin — the Algonquin Round Table — in the 20s. In fact, I would say that New York gave us, for better or worse, the concept of power in lunch.

• • •

Thanks to Laura Shapiro and Rebecca Federman for a wonderful conversation and a rushed Pret a Manger sandwich. I’m looking forward to seeing the exhibition in person soon — if you go, let me know what you think in the comments.

Despite the terminology, due to my working hours my main meal has shifted from night time (7-8pm) to around midday (1-2pm). Meal times are the same, but instead of eating a more substantial meal at night, my main meal is during the day, with a lighter, healthier meal at night. I still call them in order, Breakfast, Lunch and Dinner.

I’ve always loved the term breakfast. Break-fast as in breaking my fast whilst sleeping, is the first thing I eat early in the morning. I still consider that period to be fasting, because if I could eat in my sleep I would!

In my native Chile, we have breakfast, a dinner type meal at lunch 12-2pm, then a british inspired tea time around 5 or 6pm and a late dinner at around 9pm. Never a big meal and you’d think Chileans would be fat from never separating themselves from the dinner table, but it’s the opposite.

Good article.

In Russia, where I live, we still have Breakfast, Dinner and Supper. even if working people don’t come home and have a meal at work, it is rarely called lunch, it is still dinner.

School children and students, though, usually have breakfast, then lunch in a cafeteria at school/university, then dinner when they come home at about 3 pm (traditionally it is soup) and then supper at about 7-8 pm. In such cases dinner and supper are pretty much equal in size, in my family dinner is traditionally soup-like and supper is more like fried something.

Well, now I know where our family tradition of sandwiches with butter AND peanut butter comes from! My mom always made them that way when we were kids. Even as a grown-up, I can’t have peanut butter on toast unless the toast gets buttered first.

In England, where I grew up, we had a “school dinner” at midday — but the main meal with family was in the evening, even if we called it supper. The terminology was different, but the basic idea was the same: a midday meal out of the house, and the larger, more important family meal at home in the evening.

That’s fascinating, Amy — I had no idea lunch could still be used to refer to a snack at a time other than midday! Thanks for commenting.

If we’re sharing unsolicited advice, Laura, then I think you should read more carefully:

“[Lunch] is a former snack that only became the day’s third fixed meal as society urbanised and industrialised, and workers were unable to return home for dinner (always the main meal of the day) until late at night.”

I agree with other posters above who say this post is a little confused. You shouldn’t look at lunch at something that was added to our lives; rather, this should be about how the large midday meal with family and real food was taken out of our lives. People have always eaten a midday meal – the difference in the 19th century was that the meal became smaller and was eaten outside the home. The reason this post makes me mad is that it kind of gives support to the idea that a lunch break is something people did without for centuries and can do without again (so hey, let’s just skip lunch and keep working!!!!), when really lunch as we know it is a poor excuse for the large midday meal – with family and real food – that people ate for centuries before we started working outside the home and not being able to control our own schedules. You shouldn’t glorify 20 minutes for a cold sandwich as some kind of modern creature comfort. You should give it the unfortunate historical context it deserves.

This is just fantastic! Thank you so much.

In our family the daily meals were breakfast, lunch and supper. Dinner was what we had in the middle of the day on holidays like Christmas and Easter.

The equivalent daily meals for some of my friends in Australia and the UK are breakfast, dinner and tea.

Three meals a day seem to have been the standard for those who could afford them in the English speaking world for a very long time, but the names of the midday and evening meals have shifted around quite a bit, and have varied depending on location, family history and social class.

Dinner has always been the main meal of the day and was usually served around midday – by which time most people had already done several hours’ work. Fashionable (non-working) people took to eating dinner later and later in the day and in early C19 took a substantial breakfast circa 9-10 am and a late dinner circa3, 4 or 5 pm. As fashionable eating hours went on getting later, afternoon tea for ladies and luncheon were invented to fill the gap. Children and servants continued to eat their dinner at noon, or 1.00 pm at latest.

A celebratory dinner such as Christmas is still usually in the middle of the day – in my family at least.

In Jane Austen’s writings, people pay ‘morning calls’ before dinner – often in what we would call the afternoon. I suppose this may be why afternoon theatre performances are still called ‘matinees’.

Jim, the difference is that “dinner” is always the main meal of the day. In the BDS scheme, the main meal is eaten around midday (still pretty common in Spain), and a lighter meal is eaten in the evening. In the BLD scheme, the main meal is eaten in the evening, after work, and the midday meal is lighter and more casual.

Here in Southern Tasmania, the midday meal is ‘dinner’ also. Slowly this is dying out, but many of the youngsters still refer to it thus.

Lunch certainly existed in earlier times. It just wasn’t called lunch; the three meals were breakfast, dinner and supper.

1657 “The fallacy in this, that by eating and drinking, as oft as jets do it, be meaneth , your ordinary meals , of Breakfast, Dinner, or Supper”

1648 “some he would invite to Breakfast, some others to Dinner, a third company to Supper,”

1592 “then a fet breakfast, then dinner, then aster noones nunchings, a supper, and a rere supper. ”

The WORD lunch does indeed seem to have referred to a quick snack, but the meal already existed as one of three. I.e., what shifted was the terminology, not the practice.

I enjoyed this very much. Thanks for the insight. I’ll note that, in rural middle N. America, where dinner is still the main, midday meal, “lunch” sometimes means a late night snack even today.