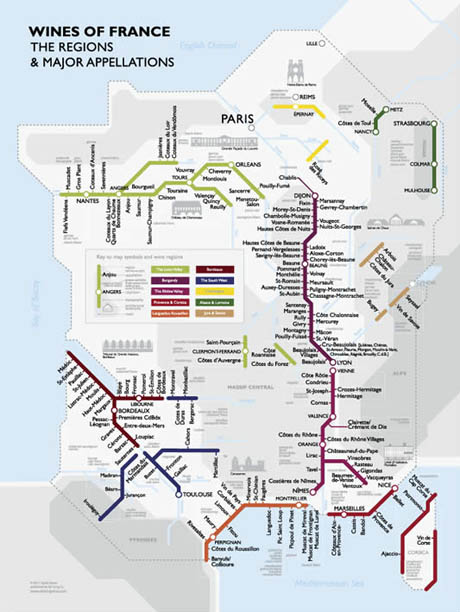

IMAGE: The Metro Wine Map of France, designed by David Gissen.

David Gissen is usually known as an architectural theorist whose publications (including a blog, and Subnature, a book I highly recommend) explore peripheral, denigrated, or otherwise overlooked aspects of urban nature — puddles, smog, and weeds — in order to re-imagine the relationship between buildings, cities, and the environment.

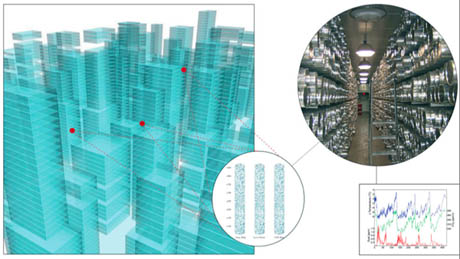

IMAGE: “Reconstruction of Midtown Manhattan c.1975,” and “Urban Ice Core/Indoor Air Archive,” two speculative proposals by David Gissen that reconstruct New York City as the world centre for intense indoor air-production and consider how that atmosphere might be archived.

In Gissen’s own projects, he proposes a new kind of architectural preservation and reconstruction that engages with the intangibles of the urban environment. For example, his “Reconstruction of Midtown Manhattan c. 1975” (pdf) removes the architectural shells of individual skyscrapers to show the city as a collective monolith of manufactured atmosphere, and his most recent installation, “Museums of the City” (currently on display at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno, as part of the Landscape Futures exhibition), visualises the application of a museum’s indoor language of display — vitrines, frames, plinths, and lighting — to the city itself.

IMAGE: From “Museums of the City” by David Gissen, project rendered by Victor Hadjikyriacou.

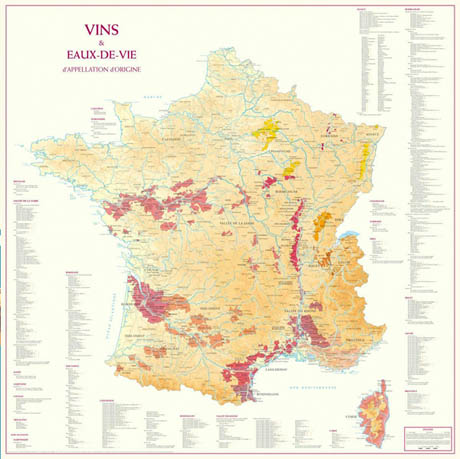

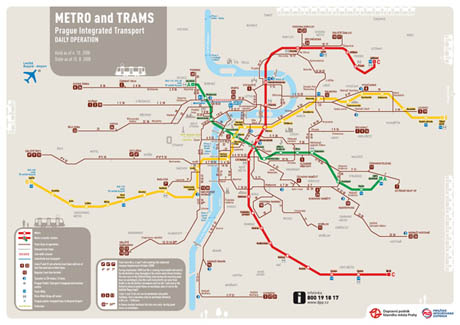

Earlier this year, however, Gissen the architectural theorist assumed a new identity: Gissen the wine nerd. In mid-January, he started to tweet about his adventures in French wine under the handle @100aocs, and quickly gained a following of sommeliers, importers, and winemakers who enjoy his unusual perspective on their field. Last week, he unveiled the first fruit of his months of tasting: The Metro Wine Map of France, which re-draws the country’s wine appellations as stops on a regional subway line.

I caught up with David by phone to talk about what this shift in cartographic aesthetic can reveal about the geography of wine. Our conversation, below, ranges from the dominance of Riedel glasses, the use of concrete in wine-making, and the best subway stop from which to embark on your own journey of wine exploration.

•••

Edible Geography: What originally inspired you to drink your way through one hundred different appellations?

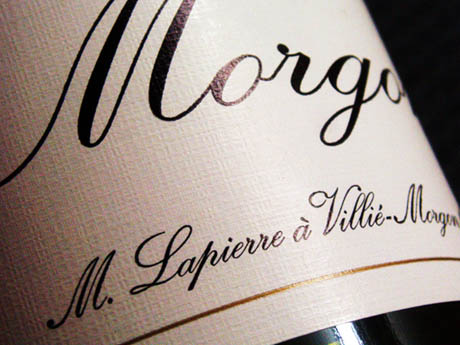

David Gissen: Like a lot of people that get obsessive about wine, I had an experience. It sounds like a religious kind of thing, but it’s true. I was at Chez Panisse and our server suggested that we have a particular bottle of wine. I hadn’t heard of it, but, as I found out afterward, it was one of the most famous bottles by one of the most famous winemakers in France. It was a 2009 Morgon by Marcel Lapierre, who is considered one of the founding fathers of the natural wine movement in France, and it was his last vintage before he died.

IMAGE: The 2009 Morgon by Marcel Lapierre, photo via.

I didn’t know any of that when I drank this wine, but it tasted like nothing I’d ever had before. As many people have said about their first wine experience, I was tasting ideas.

I’d previously had experiences like that with art, which I became obsessive about, as well as with architecture, the history of cities, and with certain kinds of geographical ideas, and then I had it with wine.

After that bottle, I wanted to learn more about wine, but I didn’t want to take a course. Instead, I thought that if I had a methodological framework for exploring wine and I shared it on Twitter, people would begin to be able to suggest things for me to try, and I would begin to assemble a course that responded to what I wanted to know, which was how a wine like that Morgon came about, how it was related to other wines, and what other wines were like it — in other words, what other wines are concerted expressions of particular philosophies or places.

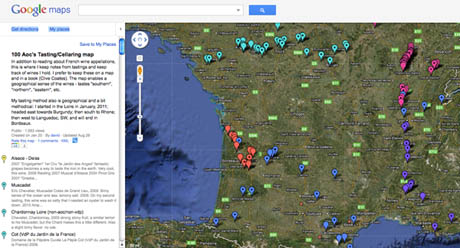

IMAGE: David’s tasting notes are stored on a Google Map.

Edible Geography: Within this framework of exploration, did you also already know you were going to keep your tasting notes on a map?

David Gissen: Yes — I thought a map would be the best way to start to understand the way that certain wines taste like they are from certain places. I recently finished Reading Between the Wines by Terry Theise, and he says that to learn wine you need a system. What he recommends is trying every Chardonnay or Cabernet Sauvignon you can lay your hands on, from anywhere in the world. I wanted to get a geographic sense of French wine, and I think my system worked well for that.

The Morgon was the initial inspiration, but the other thing is that I was on sabbatical from my teaching job at California College of the Arts this spring, working on a book and working on my installation for the Landscape Futures exhibition, and I needed a system to relax. I’m something of a workaholic, and I knew I needed a system for my hobby if I was actually going to take time off work to do it. So, every other day — well, some weeks, every day — I would get a bottle from a new appellation and try it with my wife or with friends.

IMAGE: Detail from The Metro Wine Map of France, designed by David Gissen.

Edible Geography: I followed your tasting journey vicariously on Twitter this spring, as you began to understand what “northern” or “southern” in a region might taste like. When did your Google map become a Metro map?

Gissen: I had been learning about French wine for about six or seven months, and it was the most intense, frustrating experience. A lot of people in the industry would tell me that to learn about the wines of France, you have to get to know the people who make them. The thing was, I had to budget carefully just to learn some basic geographic principles in French wine. I certainly don’t have the budget to traipse around France and meet with French winemakers for nine months. You can do that if you’re an importer, I suppose, but it seemed completely ridiculous for me to do.

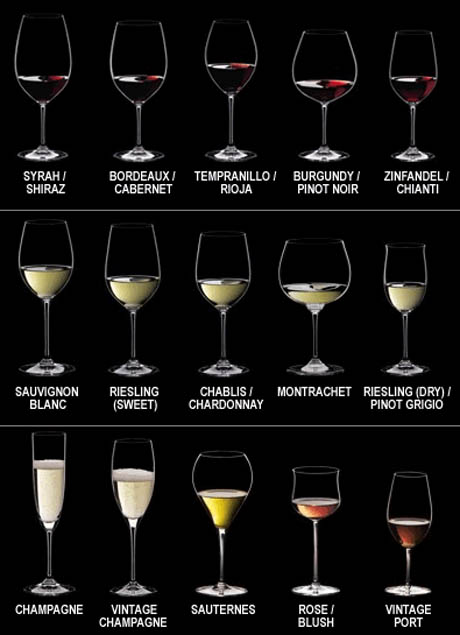

On top of that, I was just very frustrated with the fact that some basic ideas about the relationships between wine and geography that seemed so simple to me, after my own tastings, were not actually expressed simply anywhere. Part of the problem is the way the geographical description of French wine relies on a very literal languages of maps. What I mean by that is that if you look at almost any book on French wine, the maps look like the kind of thing that an explorer would use. They’re extremely literal, cartographic views, so that all the regions are drawn with very precise jagged-line boundaries, and you’re supposed to understand that this particular terroir stops just below this particular Autoroute in France, for example, and so on.

IMAGE: A typical map of French wine regions.

My feeling was that you could explain some very basic geographical ideas and principles about French wine if you used a visual language that was relational and condensed. To me, that means the language of the subway map. If you know the history of the Tube map, you know that this method of drawing abstracted London, and abandoned certain kinds of complexities of geography, in order to express more simple ideas about how stations were positioned in relation to each other and how different places within the system were interconnected.

IMAGE: Harry Beck’s original Tube map, via Transport for London.

My own condensed, relational map began with an extremely primitive line drawing. Then I realised that rather than using my Google map, I was actually starting to refer to my own proto-subway map to decide what I wanted to taste next. The subway map started informing the way I tasted wine.

I think this published version just makes some very simple regional and geographical concepts extremely clear to the beginner. And if you know a lot about wine, you might — I think some people have — appreciate the way that I’ve abstracted those concepts.

Edible Geography: Can you give some examples of the kinds of things you can learn from your map that you can’t learn from other wine maps of France?

Gissen: One thing I only learned through making the map was that all the “lines,” with just a few exceptions, follow rivers or coastlines. You would not necessarily understand, by looking at a normal French wine map, the absolute centrality of the rivers, which are the routes that the Greeks and Romans used as they were moving through France and planting vines.

Some of the rivers also connect regions. For example, you can see how the Burgundy and Rhône regions are connected through river systems. Another thing I didn’t know before doing my map, which would be so obvious to someone who knew a lot about wine, is a lot of the South West region’s most famous wines extend along the river that connect it to Bordeaux. The map shows that connection, up the Garonne or the Dordogne into central Bordeaux.

IMAGE: Detail of the key, Metro Wine Map of France, designed by David Gissen.

The map also shows all the grape varietals, in dotted boxes — a key suggestion from my publisher, Steve De Long. Some of them extend over from one region to the other, so you realise that there must be a similar kind of terroir. For example, from Beaujolais into the lower Loire, which is Cote Roannaise, is all planted in Gamay. Then, of course, the mountain ranges and topographical features are all abstracted and those show interesting connections as well.

That said, with typical maps that show the entire territory, you do get a sense of how big each wine region is. Some wine regions are large — Entre Deux Mers, for example. This map doesn’t show you the difference in production. But all maps do different things, and no map shows you everything. This map has annoyed some French wine people because it makes all the wines equal. Normal wine maps contain subtle cues that tell you how fine different areas are, but on this map, Muscadet and Volnay are exactly the same — yet a benchmark Volnay costs $120 and a benchmark Muscadet is $15.

Nonetheless, although this map is just sort of fun, you can also learn a lot about wine from it. But I don’t even care if people use it that way — what I love about it is that it pulls wine into the language of cities and urban life.

Edible Geography: Why was it important to you to create an artifact that re-framed wine using an urban aesthetic?

Gissen: My experience of Marcel Lapierre’s Morgon was in an urban restaurant. Almost everybody I’ve spoken to who is interested in wine underwent their conversion in an urban wine bar, at an urban restaurant, or with wine purchased at an urban store. Our experience of wine is really an urban one — I think that may well be historically true as well, back as far as the Greeks and Romans founding towns and then planting grapes around them. And yet the first thing that most people who love wine do in order to learn more about wine is run out into the vineyard.

I’m interested in going the opposite route, and digging deeper into the urban experience of wine. I feel as though there are so few objects or visual material that currently express that. Wine is completely overridden with a pastoral aesthetic — and by that I also mean images of the labour of one class for the enjoyment of a generally wealthier class. That type of pastoral imagery makes up ninety-nine percent of the visual culture of wine, whether you’re talking about the coolest, hippest importer’s website or the cheesiest corporate wine outfit. The urban sense of wine has yet to receive a visual language.

IMAGE: The pervasive romantic, pastoral imagery associated with French wine (this example via).

Edible Geography: With the idea being that if you use a different visual language, then you open up the relationship between wine and its environment for renegotiation…

Gissen: Exactly. What’s curious is that beer or liquor has almost no pastoralist imagery associated with it. It’s an agricultural product, like wine; it’s brewed or vinted, like wine; so why is the visual culture of beer or liquor dominated by the language of urbanism and the city, while wine imagery is bucolic?

I’m already thinking about my next wine artifact. It’s still an idea, but I’m interested in perhaps making a concrete decanter. Hardcore wine nerds are really into the effects that concrete vinification has on wine, and the taste that concrete imparts into wine. There’s an irony here that I’d like people to think about more, which is that concrete, which is obviously a material of urban origin, is being embraced by the wine world because it imparts such interesting “natural” flavours into wine.

IMAGE: Concrete wine eggs, via.

Edible Geography: Excuse my ignorance, but what on earth is concrete vinification?

Gissen: A lot of the wines that I’m interested in have typically been fermented in large wooden vats called foudres. Winemakers are increasingly experimenting with new materials in which to ferment the grapes in, particularly for the longer fermentations, and one of those materials is concrete. It’s already used in some French wines, and there’s a group of vintners called the Natural Selection Theory in Australia who all make wine in these concrete-structure eggs. The resulting wines have really interesting flavours — it’s difficult to describe, but they taste very sharp, and somehow extremely natural.

Edible Geography: Is the concrete made to a special recipe or with local rocks and water, or is it just construction industry standard?

Gissen: I have no idea. What is food-grade concrete? It’s bizarre.

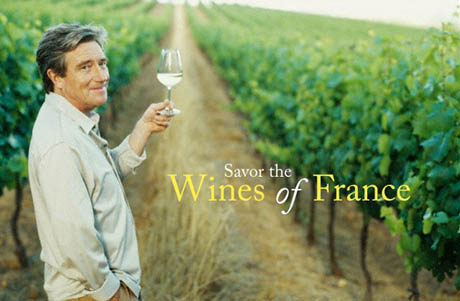

The other idea that’s behind the concrete decanter concept is to consider the way wine glass design is so dominated by Riedel. You probably know the glass series I mean — there’s a balloon shape for Bordeaux or Burgundy, and a more narrow shape for Chardonnay, and so on. They revolutionised wine drinking and have been widely copied.

I appreciate drinking wine out of them, but I do wonder: Is the wine glass as a project now over? Because one of the things I think that Riedel has unintentionally fostered is an idea that wine is just data — it’s just bouquet and colour and finish and mouthfeel, and the other data points that professional wine tasters are looking at when they’re evaluating wine. But just because a professional taster is interested in those things doesn’t mean that the other ninety-nine percent of humanity that drinks wine out of a glass has to have the Riedel data-fication experience.

I guess I’m interested in objects that will enable us to taste wine in a way that enables other experiences besides pastoralism or data.

IMAGE: Riedel’s varietal-specific glasses.

Edible Geography: When you are drinking wine, what would you say you are experiencing?

Gissen: It totally depends. When I’m in a restaurant and I’m drinking wine, I actually try not to think about it, because it becomes all-consuming. When I’m at home, I try to taste through a territory. I’ll get three bottles from a particular region but perhaps different soil types, I taste them, and I try not to get too pretentious about it. My tasting notes are completely comparative — they’re about differences and similarities to other wines, rather than things such as finish and mouthfeel.

Edible Geography: I know this started as a hobby, but how does thinking about the relational geography of wine fit with your other work re-articulating the relationship between buildings, cities, and overlooked forms of nature?

Gissen: First of all, when I hang out with wine people, the only thing that’s critical to them is what kind of wine I’m interested in, and I love that complete lack of professional obligation on my part.

On the other hand, during a lecture I gave this spring in Australia, I was talking about an architect whose work you and I both love, Philippe Rahm. I was discussing his design for underground houses that would bring up the air of the earth, and the way in which he described the house as having a terroir — a brownish taste of the earth that the people who lived there would be able to sense in their noses and minds.

Afterward, my wife came up to me and said, “Oh my god, your wine thing is not a hobby. It’s part of the same thing!” Wine is just an excuse to get all that funky shit in my mouth — all the dirt I love. My appreciation of wine is so completely subnatural that now when we go out to restaurants, I can never do the ordering. I love these dirty, filthy wines, and my non-wine friends would be completely repulsed.

IMAGE: Underground Houses, Philippe Rahm.

Edible Geography: I wanted to return to the idea of terroir, which is a hotly contested word. I think that you are perhaps on the side of people who think that terroir has a lot to do with a cultural relationship to the land, as opposed to being purely an expression of meteorological or a geological phenomena.

Gissen: I get into so many arguments with people about this on Twitter, because they say terroir is nature and I find that absurd. After all, someone chose to plant grapes somewhere or chose to brew something somewhere. I think Philippe Rahm’s way of thinking about terroir is much more interesting — it’s less rooted in the thing and more rooted in the mind of the person experiencing it. In his underground houses, the idea of terroir involves provoking the ground in some way — provoking something out it for the experience of the inhabitant of the house. In other words, terroir is not something that’s necessarily innately perceptible. It’s produced through human — in that case, architectural — intervention.

Of course, terroir is still something specific, even if it is produced by humans. I went to a screening and lecture by a guy who is really into wine, and he said two sentences about terroir and beer that completely fascinated me. He said that because of the nature of the brewing process — the way that the yeast and the hops are mashed and so forth — it’s very hard to have a sense of place in beer, but that the Trappists deliberately use open-vat fermentation so that insects, bacteria, and lady bugs, in particular, can get into the vats and give the beer a sense of where it came from.

In that case, terroir doesn’t come from the ground, so it lacks that whole romantic notion. It’s produced from spores in the air, which I find fascinating.

IMAGE: Flying Fish Exit 11, an American Wheat ale designed to refresh those leaving the Turnpike at Exit 11 to head to the Jersey Shore,via the Scranton Examiner.

Edible Geography: Speaking of beer, the taste of place, and a lack of land-based sentimentality, there’s a brewery called Flying Fish that’s creating a beer for each exit on the New Jersey Turnpike.

Gissen: That’s awesome.

Edible Geography: It’s part gimmick, but it’s actually pretty interesting, and the exits I’ve tried taste great. In this case, I suppose, the Turnpike is like the rivers of France. While we’re on the topic of the relationship between terroir and the built environment, I notice that you’ve included architectural landmarks on your map — why?

Gissen: The story behind that is that my publisher sent me a link to different subway maps from all over the world. I looked at them all really carefully, and there was one of Prague’s subway system that used cartoons of buildings and different landmarks to describe the different areas of the city.

I loved that idea, so I borrowed it. First of all, it changes the view: with the subway map, it always seems as though you’re looking down, but with the addition of these elevations, you’re now getting two different perspectives blended on the one map.

Then, because all the buildings I chose are from different periods, there’s also this great sense of movement and travel and time — you realize that you’re looking at a place that has a history.

And, of course, there’s also the urban reference. I only included one château, and I refused to include any farmhouses. The Unité’s on there, Richard Rogers’ Tribunal de Grand Instance, Carcassonne, a cathedral — I mean, how many wine maps have a socialist housing project on them?

IMAGE: A Prague subway map, via

Edible Geography: That may well be a first! So, where would you recommend someone to start their own journey through the wines of France?

Gissen: Start with the Loire, going west to east. The thing about wine is that it’s so crazy expensive, and for most regions you need to go in with people to get stuff, but the Loire is cheap. For $10 you can try an interesting Muscadet, and because it’s right there next to the ocean there’s this intense salinity. I’ve never had a Muscadet that doesn’t have a salty flavour. Move toward the center with the Chenin Blancs, which are very stony. Most of the wines in the centre are made the same grape — Cabernet Franc — so you can notice subtle and interesting variations in the taste of wines from different areas. And then if you move all the way over toward Sancerre and Pouilly Fume, the soils return again to prehistoric ocean, so you start getting flinty, salty tastes again. It’s amazing.

Meanwhile, if you detour toward the northerly Chenin Blanc appellations, like Jasnières, you can experience altitude too. They’re grown at a slightly higher elevation, so they have unusual flavourrs. The Coteaux du Loir is a really bizarre wine: the two that I’ve had taste like sweetcorn.

And with the exception of Sancerre, you can try a good example of everything in the Loire for $12 or $15.

Edible Geography: What happens after France? Will you explore new wine territories?

Gissen: I don’t know. I do feel as though there’s something that really interests me in re-contextualising wine as urban. At the end of the day, though, the map is fun. It’s something to enjoy visually and to help map out a plan for drinking some interesting stuff. And it helps keep my life weird.

I realise that I have been a little graceless.

This map is genuinely inspired. It integrates and makes sense of places I have been and places I would like to go. The Tube map was imprinted in my brain in a couple of decades of living in London, and I have watched with great interest as other cities have adopted the same logic. It really does work at a glance – the inner voice is “OK. I’m here on this blue line, then after four stops I get out and go along that red line for another three stops, then I get out …” Learning the names of the lines, and of the stations, can be deferred.

The visual element is so simple. Right now, my daughter lives over to the left on the red line of the Tube map, my son lives towards the bottom of the map on the black line. This is not to GPS standards, but in terms of finding the way there, it most certainly works.

I learned something here: I had thought the westernmost point would surely be Gros Plant, around Nantes. I have drunk many a bottle with locals who wince, shrug, and then decide to turn it into kir.

That there are two stations further west than Gros Plant is scary – if you can always taste the salt in Muscadet, you can always taste the oven-cleaner in Gros Plant.

Yeah, great article. but in reply to comment: English spelling of that city can be Marseilles or Marseille. Similarly Reims can also be Rheims.

Great article and great map. There’s a spelling mistake on the map for the city called Marseille though, it does not take an S at the end.

Congratulations — this is a such an edifying way to think about France’s wine regions. I’m thinking of starting with the Southern Rhone, myself 😉 , sometime next year. Looking forward to checking out the ancient history there.

this is so great.