Artists Miriam Simun, of Human Cheese fame, and Miriam Songster, whose olfactory works have included a reconstruction of a balm found during the excavation of Cleopatra’s perfume laboratory, are collaborating on a new project: GhostFood.

IMAGE: GhostFood branding refers to the three ecosystems from which the three menu items originate: ocean, grasslands, and rainforest.

From a street-parked GhostFood truck, Simun and Songster and their team of trained staff will be serving a menu of three items, each of which conjures up a future dining experience for a food whose supply is currently threatened by climate change. The three items on offer — cod, chocolate, and peanut butter — come from or are species that “may very well soon not be available to eat,” Simun explains. With the help of a wearable smell-dispensing device and an edible textural analogue, GhostFood truck customers will experience a simulation of a future phantom food.

“We’re going to serve the ‘ghost-cod’ deep fried,” explains Songster, “and we’ll use a vegan fish substitute made from climate-change resilient ingredients.” Combined with a prosthetic device for delivering its lost flavour, the experience is designed to offer “a simulation of how you might experience that food once it’s no longer available,” adds Simun.

IMAGE: Cod roe, via the LarvalBase Photo Archive.

Beyond over-fishing, cod’s potential future as an ocean ghost is the result of the mass drowning of its babies: cod spawn by releasing millions of eggs, and, thanks to climate-changed seawater salinity levels, those eggs are increasingly likely to sink rather than float. Meanwhile, the peanut, GhostFood’s grasslands representative, is under threat from a variety of different climate change-induced conditions, Simun explains:

If it’s too dry, flowers don’t bloom as well. The soil has to be the correct consistency, because peanuts grow in the ground and in order for the harvest to happen you need to be able to pull them out and for the peanuts to stay on the root but come out of the ground.

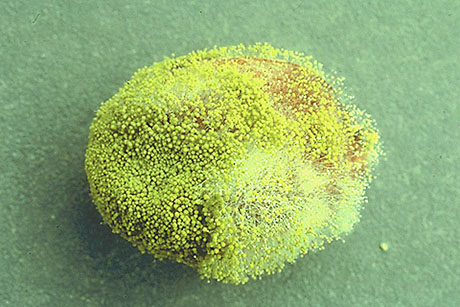

The third challenge is that if winters are shorter, the peanuts start to get this mould, which is fine for them but toxic to humans. That’s interesting, in that it’s not necessarily that there are no more peanuts, but maybe they’re not for human consumption any more. The species is OK, we just can’t use it in the way that we’re used to.

IMAGE: Aflatoxin growing on a peanut, via the American Phytopathological Society.

Chocolate, which many people are horrified to hear is already suffering supply shifts and shortages as a result of climate change, is a similarly nuanced story. Drought, pest and disease increases, and the changing temperature of the topsoil all make cacao trees harder to grow and their harvests smaller.

In West Africa, the source of half the world’s chocolate, there’s an additional wrinkle: the growing regions will need to migrate upwards in elevation to stay productive, which means more deforestation, which then further exacerbates climate change. It’s possible to imagine a future in which consumers or producers or both decide that protecting the remaining rainforest ecosystems is more important than cheap chocolate — “which would be a big fight,” Songster laughs, “but speculating about those kind of sacrifices and shifts in our relationship with a species is part of the point.”

IMAGE: Cacao pods, via.

The project, which was commissioned by the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation for Marfa Dialogues/NY as part of a series of installations and events looking at climate change through the lens of the art and science, is clearly intended to provoke dialogue rather than present certainties. According to Simun:

We’re not interested in scaremongering, and making people panic and tear their hair out about the end of chocolate. We don’t have a climate change education agenda, although inevitably we’ll end up raising awareness. Rather, we’re extrapolating a possible future, given current trends, and then exploring how we might respond it and what that might mean.

Part of that conversation will, the two Miriams hope, explore the way our relationship with a species as food tends to blind us to the fact that these plants and animals have their own places and paths in the world, the loss of which means more than just a gap on grocery store shelves.

Another, equally important discussion the dining experience is designed to inspire is about the silver linings and losses embedded in our possible technological responses to a climate-changed diet — which is where the olfactory headgear comes in.

IMAGE: Some of Miriam Simun’s very early sketches of the device: “I would ride around on the subway drawing different people, and then sketch the GhostFood device on their face. in part to have in mind that this extension would need to accommodate all the very different shapes of faces that exist (many of which can be found on the New York Subway),” she explained.

Based on sketches by Simun, this smell delivery device is a 3D-printed plastic headset that a user will wear like glasses, anchored by their ears and resting on the bridge of their nose. A scent pod with a changeable wick dangles out on a wire from the bridge, hanging more or less directly in front of the nose of the GhostFood truck diner.

The device, which also has to be strong enough to stand up to repeated sanitisation between users, is designed to deliberately draw attention to the artificial nature of the simulation, while also offering a convincing and excitingly novel way to combine textural substrates and aromas into new food experiences. Simun explains:

When I was working on it, I was looking a lot at the rituals we have around eating and the devices that we use around it. I was reading all about the history of forks, which is actually really interesting.

Then I was also thinking about how we’re starting to augment our abilities through all these different kinds of wearable technology, and also about insects that use their antennas to smell and navigate their way through the world. It was inspired by some combination of all of those things.

Songster and Simun worked with major flavour and fragrance company Takasago (which boasts that it “particularly excels in the category of corn flavors”) to develop a scent that, when added to the existing flavour of the ghost food analogue, will invoke the sensory profiles of fried cod, peanut butter, and a chocolate brownie.

IMAGE: GhostFood grasslands branding.

“The entire thing is something of a physiological experiment,” admits Songster, because flavour experience is usually largely created by retronasal olfaction, which takes place via a slightly different channel to smells that we sample through our nostrils. The flavour and fragrance units of Takasago had to work together to tackle the challenge.

This element of technological innovation to reconstruct lost “natural” flavours is central to the project, explains Simun, quoting Marshall McLuhan: “every extension is [also] an amputation.”

We use technology to extend our abilities and then also take the place of things, so you lose something and you gain something. It goes both ways.

In other words, the experience of GhostFood is not a perfect emulation of what it’s like to eat peanut butter — that, in Simun and Songster’s imagined future, is gone forever. What has replaced it is something new: better in some ways (for example, allergy-sufferers can happily enjoy the oil- and starch-based analogue and its associated scent) and, no doubt, worse in others, but, above all, different. A dire situation, and also a magical new experience, in one tasty mouthful.

IMAGE: A rendering of the GhostFood headset.

“That’s progress, right?” says Simun. “Progress is such a complicated thing. It’s so easy to reduce things to “good,” “bad,” “disaster,” “solution,” and so on. But the situations we face are a really complex web of many different emotional, physical, personal, cultural, and ecological ideas and forces all woven together and the way we deal with them is never going to be wholly positive or wholly negative. Coming to terms with that is somehow quite important.”

The very idea of GhostFood is thrilling, resonating on so many levels: the poetic ephemerality of flavour in the moment and its Proustian longevity in memory; the culinary potential of the de-extinction movement (Simun “would love for Ghost Food to serve dinosaur, if any synthetic biologists want to collaborate on that!”); shifting cross-species relationships; and even the ways that our senses combine to create flavour perception.

You can sample GhostFood at its premiere at Pop Up Place, a benefit launch party for DesignPhiladelphia 2013, on the evening of October 9, as well as in Newark, New Jersey, and New York City later in the month.