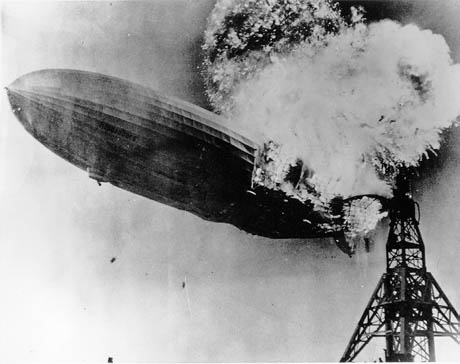

IMAGE: The Hindenburg zeppelin, which caught fire as it tried to dock in New Jersey at the end of a 1937 cross-Atlantic voyage.

Last week, the New York Post reported that “a charred bottle of beer that survived the explosion of the Hindenburg will be auctioned off this month for an estimated $7,500.” The single bottle of Löwenbräu was recovered from the airship disaster by a New Jersey fireman. Much of its original content has evaporated, and the beer that remains is “probably quite putrid to taste,” according to Andrew Aldridge, of the auction house Henry Aldridge & Sons.

This story reminded me of a rumour I heard a few years back: that drinkable vintage Champagne had been salvaged from the Titanic.

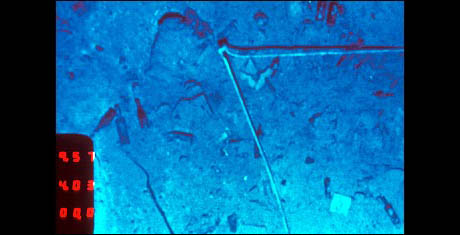

IMAGE: Wine bottles are visible among the debris of the Titanic on the sea floor in this photo taken by the 1985 joint Franco-American expedition that discovered the wreck’s location. Image courtesy of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

While trying to verify that story, I discovered that salvaging materials from the Titanic is fraught with controversy. The American government only co-funded the initial reconaissance as cover for a top secret mission to find and map the remains of two nuclear submarines, while the salvor-in-possession, R.M.S. Titanic, Inc., is currently fighting a court case to gain ownership of the artefacts it has retrieved thus far. In 1987, the U.S. Senate voted to ban the sale for profit of anything retrieved from the Titanic – but in 2002, an Australian company called Wineflyers International (whose regular customers apparently include David Bowie) announced it had sourced and sold six bottles of wine from the Titanic to “a high profile customer in Asia.”

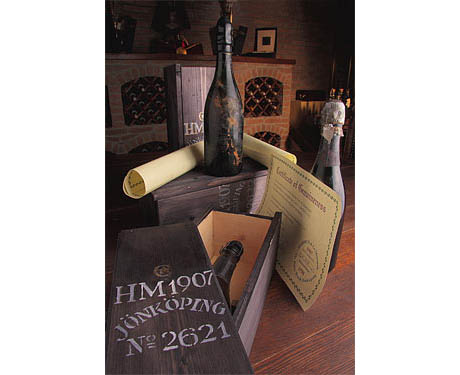

IMAGE: Cases of 1907 Heidieck & Co. Monopole Champagne were retrieved in 1997 from the wreck of the Jönköping in the Gulf of Finland. Photo courtesy Vinocellar.

In any case, the shipwrecked Champagne of my memory actually came from a different boat altogether: a Swedish freighter called Jönköping that was en route to Russia in 1916, carrying a full cargo of alcohol ordered by Tsar Nicholas II, when she was sunk by a German torpedo. Her wreck was found in 1997, and a salvage company recovered 2000 bottles of 1907 Heidsieck & Co. Monopole. Reports from the time quote Laurent Davaine, Director of Exports at Heidsieck, saying that the Champagne still “shows an amazing balance” and “a beautiful golden hue with the effervescence still present.” As of 2008, according to Newsweek, most had already been sold at auction, but there were still ten bottles for sale at the Ritz Carlton in Moscow, priced at $35,000 each

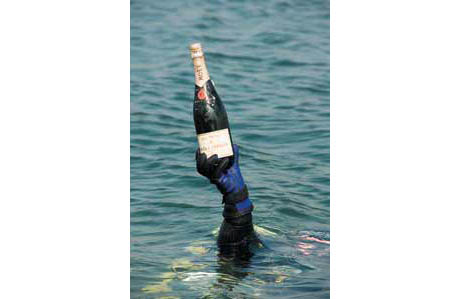

IMAGE: Diver bringing a champagne bottle to the surface, courtesy Dive Magazine.

It appears the ocean floor, if treated as a single entity, might actually be the world’s largest wine cellar – a sunken treasure trove of lost vintages awaiting rediscovery. Like squirrels digging up acorns, wreck-divers and salvage companies stumble upon another forgotten cache every few years.

IMAGE: A Cavas Submarinas bottle. According to Luxist, they have special labels that don’t come off underwater.

It is not clear whether prolonged storage at salty depth is damaging, beneficial, or indifferent in its effect on a wine’s flavour. For example, there is a Chilean winery that deliberately cellars its wine on the ocean floor. Viña Casanueva offers a Muscat-Chardonnay blend and a Cabernet that are aged underwater, under the label “Cavas Submarinas.” In mid-2005, “at least five seaside restaurants in different cities” were “offering to dive for the wines as they’re ordered,” according to another Wine Spectator article, in which we learn that:

The idea began when Patricio Casanueva, general manager of the winery, was searching the seabed for a lost anchor and was struck with a vision of a cavern filled with wine bottles and other treasures. “These wines are at least six months underwater, and with a constant temperature of 8 degrees Celsius,” he says. “Also very important is the sunlight refraction that crosses the sea and reaches the bottles. And of course, the water currents.”

IMAGE: Screen grabs of divers retrieving wine bottles from underwater cellars from the insane Cavas Submarinas promotional video. Watch the full version, complete with mermaid, on YouTube.

On the other hand, there was great oenological disappointment over the 1919 wreck of the RMS Republic, which was found in 1981. The Republic was a proto-Titanic – luxurious, owned by White Star Lines, and the largest operating cruise ship of her day, until she ran into another boat. Her salvors were actually looking for a secret cargo of American Gold Eagle coins, supposedly sent by the U.S. government “to pay for Czar Nicholas II’s Russian military buildup before the First World War.” Instead, they found a 1898 Moët & Chandon that still had “a robust, hearty taste with a pale color similar to ginger ale.” Unfortunately, after spending $10,000 per day to bring three hundred bottles to the surface, Wine Spectator reported that Christie’s “found no bottles in condition to be auctioned off.” They had all been “invaded by sulfur-producing bacteria that travel at the bottom of the sea,” according to Michael Davis, Vice President of Christie’s wine division.

Despite the risks, both scuba divers and wine collectors share an enthusiasm for underwater bottle retrieval. Dive Magazine even provides a useful overview for inquisitive amateurs, cautioning divers against popping the cork from even a single bottle until their find has been appraised by experts:

Take the case of the divers who opened and drank one of eight bottles of beer they recovered from the Loch Shiel off the Welsh coast. Jim Phillips, one of the divers, told reporters: “It was flat but it had not been contaminated by the salt water even after all those years on the sea bed. We later had the find valued at £1,000 a bottle, so that was certainly the most expensive pint I have had.”

Meanwhile, for archaeologists, the alcoholic finds are a treasure trove of information, offering clues to cultural and socio-economic preferences, shipping and trade routes, and even shifts in climate and viniculture. For example, the Titanic and Republic wine cellars are typical of luxury cruise liners of the time, according to Wine Spectator. They contained relatively few Bordeaux, compared to wines that could be served chilled, such as Champagne and Mosel, because the rumble of the enormous steam engines would dislodge sediment in the older reds.

Sampling wines from shipwrecks also offers the chance to taste the pre-history of today’s wine-making styles. A 1996 paper published in the Australasian Historical Archaeology journal discusses the analysis of wines recovered from an 1841 shipwreck – the William Salthouse, in Melbourne’s Port Phillip Bay – in terms of the evolution of Muscat. By combining chemical composition analysis with sensory data (i.e. sampling) and archival research, archaeologists with Heritage Victoria discovered that “Muscat was traditionally an unfortified style, quite different to today, due to a vinification technique called passerillage,” which created a wine with such high sugar levels that, to modern oenologists, it tastes like Sauternes.

Finally, to return to the humble Löwenbräu with which this post began, I can’t help but feel that there is a certain rock & roll, self-destructive hedonism to drinking alcohol retrieved from disaster sites. Rather than dabbling in uninspiringly predictable mountains of coke, celebrities of a more poetic nature might prefer to drown their sorrows in the wine cellars of a doomed voyage.