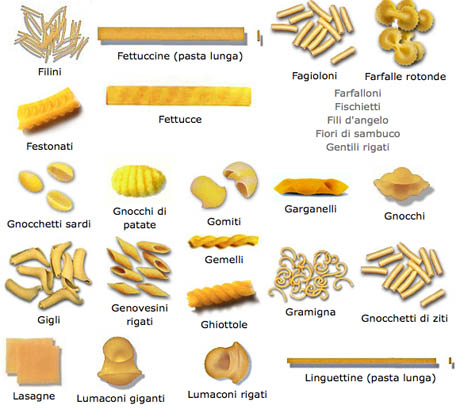

IMAGE: Some pasta shapes, from L’Enciclopedia della Pasta.

UNESCO, the branch of the United Nations that is best known for its list of World Heritage Sites, also curates a number of other programs that aim to record and safeguard natural and cultural treasures. The Global Geoparks Network, for example, seeks to promote and conserve Earth’s geological heritage, while the fantastically named Memory of the World project was launched in 1992 “to guard against collective amnesia” by preserving and disseminating archive holdings worldwide.

Other UNESCO lists catalogue significant literary cities, biospheres, wetlands, and endangered languages. Amidst this variety, there isn’t a UNESCO list dedicated to designating and protecting outstanding examples of our global food heritage. Indeed, senior UNESCO official Cherif Khaznadar is on record as saying, “There is no category at UNESCO for gastronomy.”

Nonetheless, last week, the Mexican government submitted a proposal to UNESCO on behalf of the cuisine of Michoacán. Their hope is to have its tamales, guava paste, and cotija cheese added to the Intangible Heritage List, which recognises “practices, representations, and expressions, and knowledge and skills which are transmitted from generation to generation and which provide communities and groups with a sense of identity and continuity.”

IMAGE: The typical dishes of Michoacán, via Mexico Cooks! (left) tacos de borrego a la penca, (right) blackberry tamales.

Despite these broad criteria, there are currently no foods or culinary traditions on the Intangible Heritage List. Launched in 2003, the list has inscribed a grand total of 181 expressions of intangible heritage worthy of preservation, from Albanian Folk Iso-Polyphony to the Tango, and from the Cultural Space of Jemaa el-Fna Square to the Traditional Design and Practices for Building Chinese Wooden Arch Bridges.

Thus far, however, French cuisine has been rejected twice, while Mexican cuisine has been turned down once already.

The benefits of recognition lie mainly in the boost to local pride and international renown, although there are some funds available for preservation efforts. Michoacán’s tourism secretary, Genovevo Figueroa, hopes that UNESCO recognition would correct common misperceptions of Mexican cooking as “lots of grease and spices.” Meanwhile, launching France’s second failed bid in February 2008, Nicolas Sarkozy declared that, “We have the best gastronomy in the world — at least from our point of view. We want it to be recognised among world heritage.”

Critics have been divided as to whether culinary traditions should be included on the Intangible Heritage List or not. Those arguing against tend to worry that labeling a cuisine as one of the treasures of human patrimony will have a stifling effect, discouraging innovation and marking the beginning of a slow, smug “mummification.” Their opponents counter that UNESCO is careful to define Intangible Heritage as “traditional and living at the same time,” and “constantly recreated,” and that formal recognition would help defend national cuisines under threat from globalisation and changing lifestyles.

IMAGE: China’s Intangible Cultural Heritage, (left) Chinese calligraphy, (right) dim sum

IMAGE: France’s Intangible Cultural Heritage, (left) Aubusson tapestry, via UNESCO, (right) a croissant.

Ultimately, it seems that UNESCO may yet accept that culinary traditions are a cultural expression as fundamental to identity and worthy of recognition as dance, theatre, or music. In 2009, the Section of Intangible Cultural Heritage held a special Expert Meeting on Culinary Practices, and in their October 2009 report on rejected nominations, the Bureau of the 4th Session of the Committee noted that many requests for inscription had failed due to incomplete applications, rather than fundamental ineligibility.

One day, perhaps, the traditions embodied in dim sum will take their place alongside Chinese calligraphy, and the artisanal craft of croissant-baking will be accorded the same respect now due to Aubusson tapestry….