IMAGE: A random mutation caused this Golden Delicious apple to turn half-red, half-green. According to Susan Brown, she can breed apples with a stable variation of this mutation that creates candy-cane red stripes on a pale yellow-skinned apple. Photo ARCHANT via The Daily Telegraph.

In a 2011 talk titled “Taste the Apples of the Future,” Cornell University professor Susan Brown, one of only three commercial apple breeders in the United States, offered an enticing glimpse of yellow-red chimeras, pink-fleshed varieties, and the non-browning NY-674, whose resistance to discoloration was discovered by chance during an equipment failure.

Before moving onto her own, more practical work developing higher yielding, earlier fruiting varieties that are resistant to cold storage “scald,” Brown also mentioned that in Japan, farmers were already growing apples with built-in branding — the Japanese symbol for “good health” tattoed onto their skin by the sun.

IMAGE: Field Worker & Stenciled Apples, Fall, Aomori Prefecture, photograph by artist Jane Alden Stevens.

In 2007, Cincinnati-based artist Jane Alden Stevens spent four months in Japan, documenting the extraordinary attention its orchardists put into growing perfectly beautiful apples. In addition to culling blossoms to reduce over-crowding and ensure regular, large fruit, and then hand-pollinating them using powder-puff wands, Japanese farmers put a double-layer of wax paper bags around their baby apples for most of the growing season.

IMAGE: Hand Pollination #1, Spring, Aomori Prefecture, photograph by artist Jane Alden Stevens.

IMAGE: Bags for Apples, Early Summer, Aomori Prefecture, photograph by artist Jane Alden Stevens.

The bags do double duty, shielding the apples from pests and weather damage while also increasing the skin’s photosensitivity. In the autumn, a few weeks before harvest, the bags are removed — first, the outer one, revealing the fruit’s sun-deprived, pearly white skin, and then, up to ten days later, the translucent inner ones, whose different colours are chosen to filter the light spectrum in order to produce the desired hue.

IMAGE: Removing Inner Bags #1, Fall, Aomori Prefecture, photograph by artist Jane Alden Stevens.

As they are finally exposed to the elements for the final few weeks before harvest, the most perfect of these already perfect apples are then decorated with a sticker that blocks sunlight to stencil an image onto the fruit. This “fruit mark” might be the Japanese kanji for “good health,” as Susan Brown mentioned. Others have brand logos (most notably that of Apple, the company), and some, according to Stevens, are “negatives with pictures. One Japanese pop star put his picture on apples to give his entourage for presents.”

IMAGE: Photogram Beneath the Stencil, Fall, Aomori Prefecture, photograph by artist Jane Alden Stevens.

Far from being the apple of the future, however, Stevens tells the University of Cincinnati magazine that apple bagging and stencilling is in decline. When she visited Japan in 2007, apple bagging was applied to about thirty percent of the crop, “but fifty years ago, it affected seventy percent,” Stevens says. “Farmers do it themselves, but their children aren’t following in their footsteps, and there aren’t enough laborers to do the work.”

Fruit-marking is not even a recent — or an exclusively Japanese — development. I first came across mention of it in Suzanne Freidberg’s wonderful book, Fresh, which describes the efforts of the nineteenth-century fruit-growers of Montreuil to “brand” their apples for the novelty-seeking Parisian luxury market. Wives and children spent their winters folding and gluing thousands of paper bags, and their springtime covering up each individual apple at a rate of up to 3,000 per hour.

IMAGE: L’ensachage (fruit bagging), from the “Le travail quotidien” section of the Société Régionale d’Horticulture de Montreuil online archive.

The introduction of fruit stencils followed quickly behind, initially applied to the fruit with egg white or bave d’escargot (snail slime). According to Freidberg, particularly ambitious growers also developed negatives on their apples, in a kind of “fruit photography”:

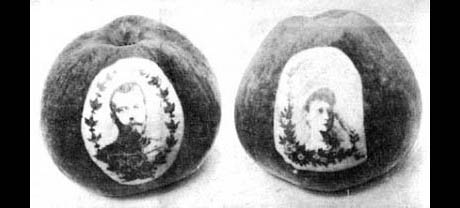

The marked fruit of the Montreuillois first won renown at the 1894 Saint Petersburg exhibition, where they presented the czar of Russia with an apple stenciled with his own portrait. King Leopold of Belgium, Edward VII of England, and Teddy Roosevelt received similar fruits.

IMAGE: Photographic apple portraits of the Tsar of Russia and his wife, via the website of artist Pauline Fouché.

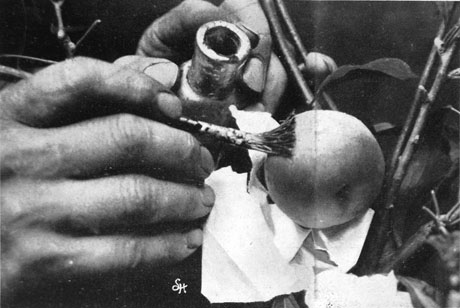

IMAGE: Applying gelatin glue to an apple, from the “Le travail quotidien” section of the Société Régionale d’Horticulture de Montreuil online archive.

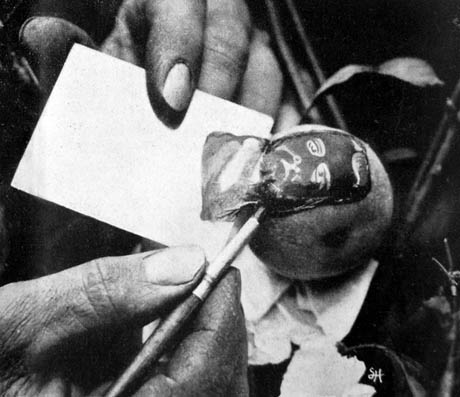

IMAGE: Peeling away a stencil on an apple, from the “Le travail quotidien” section of the Société Régionale d’Horticulture de Montreuil online archive.

The idea of fruit-marking may well have come from an even earlier source, Freidberg notes, mentioning a reference in an Arabic treatise on agriculture from the twelfth century. Nonetheless, by the 1930s, the practice was all but extinct in France, as Montreuil was absorbed into the Parisian suburbs and an industrialising agricultural sector produced ever cheaper mass-market fruit.

Still, after three years of trying, the Société Régionale d’Horticulture de Montreuil appears to be successfully reviving the lost art for today’s hobbyists and home gardeners. Their album of recent successes includes swirling dragons and tribal imagery worthy of any would-be Ink Master; a twenty-first century apple is more likely to sport a Che tattoo than a king or tsar.

IMAGE: A stencil of Che Guevara, from the fruits marqués section of the Société Régionale d’Horticulture de Montreuil website.

Perhaps Cornell’s Susan Brown is onto something with apple stencils, after all. Although the commercial growers she works with are unlikely to pursue fruit bagging and photography, at least in the near future (the labour costs are simply too high), the technique seems ripe for rediscovery by today’s artisanal producers. Banksy could market a line of stencils for London’s fruit trees, Brooklyn growers could develop photographs of local landmarks on their heirloom varieties, and suburban families could entice their children into choosing apples over sweets by imprinting them with cartoon characters. Move over, bacon — tattooed apples are the next trend.