“I was leafing through the first edition of Water-Works Management and Maintenance (1907) and came across this lovely little table,” began a recent email from Michael Cook, an intrepid explorer and talented photographer of subterranean hydrology.

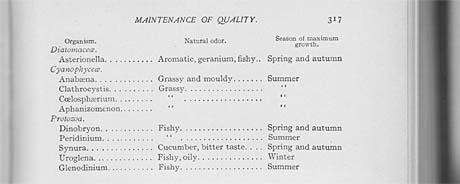

IMAGE: Chart from Water-Works Management and Maintenance, scanned by Michael Cook.

The table in question is on page 317, in a chapter titled “Maintenance of Quality,” and it correlates varying tastes of drinking water to the “oils or other substances” of the particular organisms contaminating it and their seasonal growth.

In their subsequent discussion, authors Winfred D. Hubbard and Wynkoop Kiersted takes pains to distinguish between these grassy and fishy odours, which are naturally produced by the organisms while they are alive, and the “much more disagreeable” tastes produced by their death and subsequent disintegration. Cyanophyceae, for example, give drinking water a grassy taste when blooming in blue-green algal scums at the surface of reservoirs. However, upon their decay (which is hastened by the elevated heat of pipework in the summer), “the odors produced are aptly termed ‘pig-pen’ odors.”

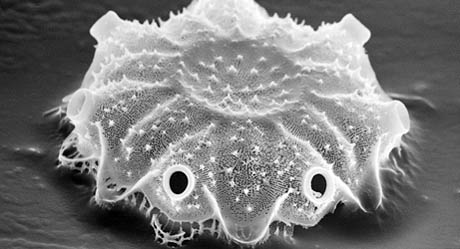

IMAGE: Scanning electron microscope image of a fossil marine diatom, from the collection of the (British) Natural History Museum.

However, despite the description of Asterionella-contaminated water as having an “aromatic, geranium” scent, and of Synura-water’s “cucumber” taste, drinking water connoisseurs do not eagerly anticipate their arrival each spring and autumn, savouring the natural, seasonal flavours of local reservoir ecology.

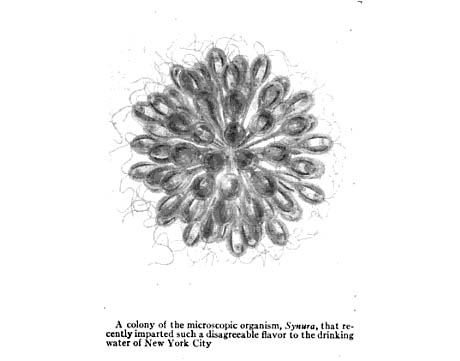

Indeed, the opposite is true. In 1922, following on from an article titled “Luminescent Worm Attacked by a Crab,” the bi-monthly publication of the American Museum of Natural History reported that Synura’s colonisation of the New York City water supply was responsible for the “fishy or cucumber-like taste that has proved so objectionable.” (The silver lining: increased attendance at the museum.)

On account of the popular interest in Synura, the protozoan animalcule which has recently been spoiling the taste and odor of the drinking water of New York City, a glass model representing a colony of this organism, prepared by the department of lower invertebrates, was placed on special exhibition in the foyer of the American Museum in January and has attracted considerable attention. This is evidenced by the fact that on Sunday, January 15, when Synura was at the zenith of its effectiveness, 15,000 persons visited the Museum as compared with the average Sunday attendance of 5000.

IMAGE: Illustration from the bi-monthly publication of the the American Museum of Natural History, NYC, January-February Issue 1, Volume XXII, 1922: “A colony of Synura, when fully grown, is composed of about fifty individuals, which radiate from a common center by slender prolongations of protoplasm, and measures about 1/250th of an inch in diameter. It gives off an oily substance which spreads rapidly through the water, causing the fishy or cucumber-like taste that has proved so objectionable.”

A handful of New York Times articles from the same month describe attempts to wipe out the “flavor bug,” which tastes “fishy to some palates and like cucumbers to others,” and “may even have tonic properties” despite its unpalatability. City officials began their efforts by building a bypass to cut out the Kensico reservoir at Valhalla from the New York water supply system. However, as the Times laments later in the month, “that Synura taste again taints water,” with a newly discovered colony in the Ashokan reservoir producing the “most pungent fish-and-cucumber flavor” yet recorded.

With the city planning a full chemical attack using the deadly “copper sulphate method,” an anonymous engineer speculated that “the visitation of Synura was likely to be followed by a worse plague of Asterionalla, on the theory that the extinction of the Synura would throw the food supply of that animalcule to its sister micro-organism.” The threat of geranium-flavoured water was not, reported the Times, being taken seriously by officials of the Water Department.

Curiously, in the same article, city officials are at pains to point out that the fishy taste should not be attributed to minute fish “that occasionally get through.”

A few years back, for instance, there were a number of complaints from Brooklyn that small eels and sometimes fair-sized ones came through the water mains. […] Minnows an inch or two in length have been reported, but rarely. They do not contribute anything to the fishy taste in the water.

IMAGE: Sedimentation and filtration pools at the Woodward Avenue Water Treatment Facility, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. Photo by Michael Cook, commissioned by the Hamilton Museum of Steam and Technology.

Eighty-six years later, the American Museum of Natural History was again conducting a sensory evaluation of New York City’s tap water, this time by holding a regional Tap Water Taste-off on their steps. The city’s municipal water placed second, beating that of New Windsor (Orange County), Dix Hills Water District (Suffolk County) and Croton-on-Hudson (Westchester County). Indeed, in 2010, New York City’s water was ranked in second place nationally by the American Water Works Association, behind only Stevens Point, Wisconsin (pop. 25,000). A triumphant Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel article provided more detail on the association’s taste test process:

The group has a standing body of scientists and industry engineers called the Taste and Odor Committee, which furnished the panel of three judges for Tuesday’s national finals.

“This is exactly the same as wine tasting,” without the possible inebriation, said Pinar Omur-Ozbek, a professor of water engineering at Colorado State University and one of the judges.

For the contest, water is served at room temperature because cold temperatures mask some unwelcome tastes. Criteria cover a wide gamut, from bitterness and ozone to dryness and aroma. Judges drank from glasses identified only by a number. Each of the tap water samples was scored on a scale of one to 10.

IMAGE: Judges Pinar Omur-Ozbek (left) and Monique Durand tasted tap water from utilities across the United States. Photo by the American Water Works Association, via the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel.

The Stevens Point water was praised by the judges for its balanced mineral content, although Omur-Ozbek pronounced it “a little drying at the end.” Since then, New York City’s reputation has taken a beating after sampling last year showed elevated levels of lead in fourteen percent of the city’s homes. The Department of Environmental Protection blamed increased levels of acidity in the water, which makes it more corrosive to the city’s older lead service lines or solder pipes. Fortunately (or unfortunately), the Centers for Disease Control confirms that “you cannot see, taste, or smell lead in drinking water.”

From an objectionable fish-cucumber flavour to an award-winning taste contaminated with scent-free danger, the sensory history of New York City’s tap water tells a story of evolving terroir. Over the past century, infrastructural, industrial, and technological shifts have changed both the chemical make-up of urban water and the way it is treated, tested, and perceived.

IMAGE: A water distribution main in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, photo by Michael Cook, commissioned by the Hamilton Museum of Steam and Technology

When Hubbard and Kiersted were writing Water-Works Management and Maintenance, bacteriological pollutants in water had only recently been discovered. Now, the oily, fishy taste of Uroglena in the winter or the summertime grassiness of Anabaena are flavours that are all but lost in the United States, thanks to improvements in water purification techniques.

However, alongside those advances has come the simultaneous addition of an enormous range of novel substances into our water supply, and an improved ability to detect them in our water, even if not with our unaugmented senses. As Charles Fishman writes in his new book, The Big Thirst, pharmaceuticals, runoff and seepage from farms, mines, and gas-drilling, and “all the products of modern life — from shampoos and detergents to the fire-retardant chemicals that infuse our children’s pajamas — are depositing a faint rainbow of contamination in our rivers, lakes, and reservoirs.”

IMAGE: Chlorination lines and a variety of other piping in service tunnels beneath the Woodward Avenue Water Treatment Facility in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. Photo by Michael Cook, commissioned by the Hamilton Museum of Steam and Technology.

These micropollutants, and our enhanced awareness of them, are the reason that nearly sixty percent of Americans told Gallup that they worry about drinking water “a great deal,” Senator Specter of Pennsylvania (a state which permits fracking) went on record at a town hall meeting saying that “I don’t trust tap water,” and bottled water is a $21-billion-a-year industry in the United States, despite the fact that the purity of bottled water is not nearly as tightly regulated as that of drinking water.

Nonetheless, spurred on by the gourmet messaging of bottled water, tap water is fighting back. “The past 20 years have seen major advances in the study of tastes and odors in water,” claims the American Water Works Association, adding that utilities have invested heavily in the “aesthetics of water.” Venice has already rebranded its municipal supply under the label Acqua Veritas; can “Chateau Bloomberg” be far behind?

A huge thanks to Michael Cook for sending me the table and letting me use a few of his fantastic photographs.

Discover more from Edible Geography

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

6 Comments

Hi, I found your article today as I searched for, why does my tap water taste of cucumbers! I found this article very interesting, I am over in the U.K. and wonder what the differences are when it comes to the monitoring of. Tap and bottled water here.

A few hours ago I messaged the water supplier about the cucumber taste and was told they have never heard of that before! … not sure I believe them. They took my address and phone number and are investigating. I sent them your blog!

Interestingly the cucumber taste is mild direct from my tap yet after being filtered with a brita water filter the cucumber flavour and smell is very clear! So strong I had to ask my son if he had put cucumber in it!not sure if that the filter, temperature or both contributing to the enhanced cucumber flavour.

What I can’t work out is, is it safe? Is it safe to drink water with synura?

I love your blog.

I live in New Orleans. My oldest brother is a drinking water engineer with the Sewage and Water Board here. My father, uncles, and cousins, all worked for the S & WB also, in drainage and wastewater treatment. We get our drinking water from the Mississippi River. My understanding is that every community in the watershed takes its’ drinking water upstream and releases its treated wastewater downstream from the community. I guess that means the water we get from the tap has already been through many of the human digestive systems, faucets, toilets and industrial plants in the central United States.

During many summers we get blooms of microorganisms that leave a strong musty taste in the water which is not removable by treatment. The advice is to drink it ice cold or flavored. My brother took my wife and me on a tour of the treatment plant once at our request, and the process is big and industrial. It yields a very clear and delicious drinking water at the plant. How clear and clean it is when it comes out of your tap depends on how far away from the plant you are.

Easy: Michael Cook, the urban explorer and photographer who sent me the table is based in Toronto and so it seemed like a great opportunity to showcase his photographs of a municipal water treatment system, which were commissioned by the Hamilton Museum of Steam and Technology. Besides which, the post is really about the ingredients and sensory qualities of drinking water rather than about any one city: I simply use the Synura outbreak in New York as an example because it’s well-documented and because NYC tap water is now known for its taste quality.

Fascinating. I do wonder, though, why they used photographs of Hamilton (my city!) in an article about New York?

This reminds me of a recent interview I read with the semi-nomadic Austrian culinary group AO&. During their NYC intensive space occupation, they created a dinner using only products that they collect themselves, and the first course was NYC tap-water.

this is so interesting! a great thorough overview. i learned a lot!