IMAGE: Watermelons at the Central de Abasto in DF. All photos by the author unless otherwise noted.

IMAGE: La Central de Abasto from a helicopter. Photo by Oscar Ruiz.

La Central de Abasto de la Ciudad de México is enormous. It sprawls across a 327 hectare site on the eastern edge of the D.F., dwarfing fellow wholesale food markets such as Hunt’s Point (24 hectares), Tsukiji (23 hectares), or even the massive Rungis, outside Paris (232 hectares).

La Central has its own postcode, its own 700-member police force, and its own border-style entry gates, but during my visit, its enormity truly hit home only when we had to take a taxi to get from flowers to fish. It was a solid fifteen minute ride from one section of the market to another!

IMAGE: Border control at La Central de Abasto. Photo via.

IMAGE: Official map of La Central de Abasto.

When the Central de Abasto was opened in 1982, approximately eighty percent of Mexico’s food supply passed through its 111 kilometres of passageways. In other words, an incredible four fifths of everything that every Mexican, from Cancun to Monterrey, ate every day passed through one single site in the nation’s capital. It was “one of Mexico’s last experiments in central economic planning,” as sociologist Gerardo Torres Salcido told USA Today.

Even today, between twenty and thirty percent of the country’s food is sold at La Central. According to David Lida (whose enjoyable book about Mexico City, First Stop in the New World, contains an entire chapter on food, and who I was lucky to see in conversation as Jace Clayton’s guest at Postopolis! DF), “on a daily basis thirty thousand tons of food are trucked here from the rest of the country, and sold to three hundred thousand customers — mainly people who sell in smaller markets, to restaurants and food stands all over the city.”

In 2009, La Central was the second only to the Mexican stock exchange in business volume. Lida’s description continues:

In 2009, La Central was the second only to the Mexican stock exchange in business volume. Lida’s description continues:

About $8 billion a year changes hands, mostly in cash; as such, merchandisers are prime prey to kidnappers. One vendor handed over half a million dollars to have his son released from captivity. He had that much money lying around at home; it was his float.

When we arrived at La Central at 5:30 a.m. one Thursday morning during Postopolis! DF, things were still pretty busy. For the most part, traffic consists of men (cargadores) pushing trolleys or pulling handcarts at a half-run, on which anything from two to twenty pallets of mangoes, crates of canteloupes, or boxes of oranges are stacked.

When we arrived at La Central at 5:30 a.m. one Thursday morning during Postopolis! DF, things were still pretty busy. For the most part, traffic consists of men (cargadores) pushing trolleys or pulling handcarts at a half-run, on which anything from two to twenty pallets of mangoes, crates of canteloupes, or boxes of oranges are stacked.

If you are in their way (there is almost no way not to be), the cargadores whistle — and, by the end of our visit, I had started to notice that the pitch and phrasing of these whistles varies according to the navigational information it communicates. In other words, “Passing on your left!” sounds different from “Watch out, I’m about to cut you off.”

Their job must be brutal, particularly since the pedestrian walkways between aisles are raised up a level to allow lorries to pass beneath — a clever design that means each delivery involves negotiating several concrete ramps. What’s more, according to Lida:

Their job must be brutal, particularly since the pedestrian walkways between aisles are raised up a level to allow lorries to pass beneath — a clever design that means each delivery involves negotiating several concrete ramps. What’s more, according to Lida:

The cargodores do not even earn a salary. Indeed, to rent their handcarts, they have to pay a little over a dollar a day to a character known as El Chino, a former street child and cargador himself. The workers vary between twelve and seventy years old. They charge between twenty and forty cents per box, depending on how heavy the load is and how far it has to be carried. An old man calculated that he earned about seven or eight dollars for a day’s work.

In between jobs, and as the flow of trade slows down, the trolleys double as backrests, seats, and even beds.

In between jobs, and as the flow of trade slows down, the trolleys double as backrests, seats, and even beds.

We began in the fruit and vegetable section, which stood out for its carefully ordered displays and fantastic signage. Oranges and potatoes were fed through a sorting machine, but even mangoes were carefully boxed by size, a task that could only have been done by hand.

We began in the fruit and vegetable section, which stood out for its carefully ordered displays and fantastic signage. Oranges and potatoes were fed through a sorting machine, but even mangoes were carefully boxed by size, a task that could only have been done by hand.

Each display was topped by a sign — occasionally hand-lettered, but for the most part pre-printed. Many said fairly predictable things, like “Best Quality!” and “Lowest Price!” Others seemed to show a delightful sense of humour, such as the green beans “Without Cholesterol!” or the carrots “As Seen On TV!”

Each display was topped by a sign — occasionally hand-lettered, but for the most part pre-printed. Many said fairly predictable things, like “Best Quality!” and “Lowest Price!” Others seemed to show a delightful sense of humour, such as the green beans “Without Cholesterol!” or the carrots “As Seen On TV!”

Still others professed surprise, delight, and teenage enthusiasm: “How cool!”, “This is the bomb!” and “F***ing great grapes!”

Still others professed surprise, delight, and teenage enthusiasm: “How cool!”, “This is the bomb!” and “F***ing great grapes!”

The fruit and vegetable section then spilled over into a set of open-walled pavilions, in which men and women stripped the thorns off nopales and washed carrots.

The fruit and vegetable section then spilled over into a set of open-walled pavilions, in which men and women stripped the thorns off nopales and washed carrots.

We were trying to find the flower market, but were waylaid by a corridor filled with Hallmark-style junk.

We were trying to find the flower market, but were waylaid by a corridor filled with Hallmark-style junk.

Dotted throughout the distinct sections were snack vendors, doing a brisk trade in tamale sandwiches (the cargadores need double carbs), freshly-squeezed juice, and Nescafé. I took photos of the youngest juicer and the most beaten-up pot I saw.

Dotted throughout the distinct sections were snack vendors, doing a brisk trade in tamale sandwiches (the cargadores need double carbs), freshly-squeezed juice, and Nescafé. I took photos of the youngest juicer and the most beaten-up pot I saw.

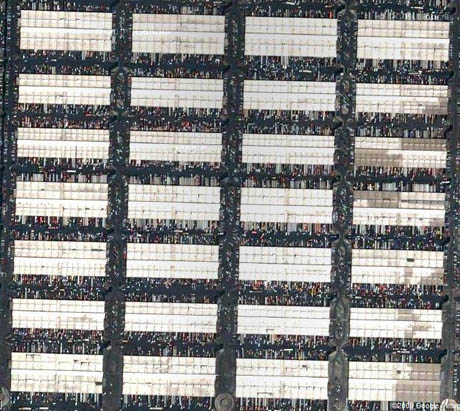

La Central de Abasto was designed by celebrated Mexican architect Abraham Zabludovsky, better known for his Museo Tamayo and Biblioteca Nacional. Its vast, modular forms are certainly striking, particularly when seen from above.

La Central de Abasto was designed by celebrated Mexican architect Abraham Zabludovsky, better known for his Museo Tamayo and Biblioteca Nacional. Its vast, modular forms are certainly striking, particularly when seen from above.

IMAGE: Satellite photo via Google Maps.

Frequently, however, the hangar-like shapes have been filled with a variety of random structures — storage or office spaces. The business of food distribution has generated its own forms within the shelter provided.

Frequently, however, the hangar-like shapes have been filled with a variety of random structures — storage or office spaces. The business of food distribution has generated its own forms within the shelter provided.

The scale of transactions seemed to vary wildly, with fresh produce leaving the market piled high in refrigerated lorries, ramshackle trucks, and even taxis.

The scale of transactions seemed to vary wildly, with fresh produce leaving the market piled high in refrigerated lorries, ramshackle trucks, and even taxis.

La Central was built to replace an older, smaller wholesale market, La Merced, just as Rungis was built to replace Les Halles. In both cases, the market had expanded beyond its central site, and was denigrated by city officials as cramped, dirty, and unsafe. La Merced was (and still is) notorious for its underage prostitutes; Les Halles — Zola’s “belly of Paris” — was equally surrounded by rough-edged bars, restaurants, and brothels.

La Central was built to replace an older, smaller wholesale market, La Merced, just as Rungis was built to replace Les Halles. In both cases, the market had expanded beyond its central site, and was denigrated by city officials as cramped, dirty, and unsafe. La Merced was (and still is) notorious for its underage prostitutes; Les Halles — Zola’s “belly of Paris” — was equally surrounded by rough-edged bars, restaurants, and brothels.

IMAGE: Les Halles butchers enjoying an after-work drink, Paris, 1962. Photo by Tom Palumbo via kottke.

Cities with a centralised food distribution system traditionally kept markets close to the seat of government, recognising the power of food as a political tool. That proximity was intended to help kings and ministers maintain tight control over the urban populace through the supply of food, but as cities and the markets that fed them grew, the strategy backfired. As Carolyn Steel puts it, in her excellent book, Hungry City: “By concentrating all the city’s food in one place, they created a powerhouse strong enough to defy them.”

By the 1970s, as Robert Moses rammed thirteen expressways through New York City, it seemed rational to authorities in Paris and Mexico City to start afresh, and move the messy business of food to spacious, orderly, hygienic, and purpose-built facilities at a safe distance outside town. La Central de Abasto’s stated mission is to: “Be the axis of the country’s food supply system, in order to regulate the market and offer the consumer quality and price.”

If the construction of La Central tells us a fascinating story about the evolution of governmental attempts to control food in order to tame cities, the market’s declining market share, down to handling between twenty and thirty percent of the nation’s food supply from eighty percent when it was first built, is testament to radical shifts in scale within the food business.

If the construction of La Central tells us a fascinating story about the evolution of governmental attempts to control food in order to tame cities, the market’s declining market share, down to handling between twenty and thirty percent of the nation’s food supply from eighty percent when it was first built, is testament to radical shifts in scale within the food business.

In other words, La Central was built to be the giant hub that tied together smallish farmers and merchants with smallish tianguis and restauranteurs. Food flowed through a single site that connected producers to vendors in a process that theoretically created greater efficiency and more competitive prices.

But following on from NAFTA in the early 1990s, food producers and vendors have consolidated and expanded in scale, shrinking the role of the hub in the middle. Walmart has set up its own supplier relationships and distribution networks; Smithfield Factory Farms is perfectly capable of finding customers without trucking its pigs all the way to a covered market on the outskirts of Mexico City.

But following on from NAFTA in the early 1990s, food producers and vendors have consolidated and expanded in scale, shrinking the role of the hub in the middle. Walmart has set up its own supplier relationships and distribution networks; Smithfield Factory Farms is perfectly capable of finding customers without trucking its pigs all the way to a covered market on the outskirts of Mexico City.

Although supply and demand no longer meet at one central market, Mexico’s food system has not decentralised — it has just centralised elsewhere along the chain.

According to USA Today, a 2008 government report concluded that La Central was gradually shifting toward small wholesale or retail customers, “meaning it is basically just becoming a big public market.”

According to USA Today, a 2008 government report concluded that La Central was gradually shifting toward small wholesale or retail customers, “meaning it is basically just becoming a big public market.”

Trucking in food from around the country in order to truck it out again a few hours later certainly seems to make no sense in terms of Mexico City’s already disastrous congestion problems. It’s also easy to imagine the food safety issues, from terrorism to traceability, associated with concentrating eighty percent of the national food supply in a single site.

Trucking in food from around the country in order to truck it out again a few hours later certainly seems to make no sense in terms of Mexico City’s already disastrous congestion problems. It’s also easy to imagine the food safety issues, from terrorism to traceability, associated with concentrating eighty percent of the national food supply in a single site.

Unfortunately, the Central de Abasto system is not being replaced with a solution that makes those problems any less pressing.

Despite its transformation, La Central still preserves some of what made central markets such a vital part of the city: noise, rubbish, smells, and a heterotopic mixing of rich and poor, city and countryside. Overwhelmed by its size, chaos, and the sheer volume of food, a visitor can gain “an awareness of what it takes to sustain urban life,” to again quote Carolyn Steel.

By way of contrast, I highly recommend this gorgeous video of the clean, well-lit, and gently bleeping spaces of New York’s Hunt’s Point Food Distribution Center, as shot by fellow Postopolis! DF participant and Urban Omnibus project director, Cassim Shepherd.

[NOTE: This post is part of a series of reports from my time in Mexico City as part of Postopolis! DF, which was presented by Storefront for Art and Architecture from June 8 to June 12, 2010. I owe an enormous thanks to Daniela Hernandez, Rodrigo Escandon, and Blair Richardson, who heroically got up at 4:30 a.m. after a night of parties and concerts, in order to help me navigate La Central!]

Comments

9 responses to “The Axis of Food”

Great post. I had no idea such a place existed.

And, Prudence, you’re my new hero:-)

I have a funny feeling Seth knows what “pedantic” means too. And yet…

Your post made it to Metafilter

Great report of a market I never heard of. I have to know more of this.

I’m overwhelmed…my next destination.

Thank you!

And to think that this was my house as a child – until I was 14 years old- actually living inside of the Mercado . . as a homeless.

Thanks, Seth — you’re quite right. But consider me a “loosey-goosey defender” of the modern usage… Especially since, as Janadas Devan writes in the Straits Times, quoting Fowler, “It is more difficult to find fault with ‘enormity’ used of the size or immensity or overwhelmingness of abstract concepts, especially when any element of departure from a legal, moral or social norm is present or is implied.’” La Central may be enormous in size, but in terms of the Mexican food system, its enormity is breathtaking!

You ought to look up the definition of “enormity.”

Great post. You really paint an accurate picture of what it’s like there. I especially loved the photos of the “no we’re not crazy” watermelons.

what a fantastic story and images!!!