IMAGE: Rainbow trout, via.

Michael Pollan’s Botany of Desire popularised the ingenious idea that the biographies of plants provide us with a mirror in which we can see our own history, desires, and values. The triumph of corn, for example, tells us a wealth of stories, from the biological imperative behind our weakness for sweetness to the economic drivers that lead us to subsidise commodity crops so they sell for less than they cost to grow. The relationship is a feedback loop whereby corn has evolved to suit the needs of industrial agriculture, which supplies a food system that has been shaped by corn.

Or, as Michael Pollan puts it, “We are all now being manipulated by corn.”

IMAGE: “The Interior of the U.S. Fish Commission’s Central Station in Washington D.C. The jars in the background are hatching jars for eggs. Fish and eggs from all over the world were collected and distributed from this room.” From the National Archives via Anders Halverson’s website.

If, like me, you are not an angler or an ecologist, the rainbow trout might not figure largely in your imagination. It should though: not only do state and federal agencies dump an incredible 25 million pounds of rainbow trout (about 100 million fish) into American rivers each year according to journalist Anders Halverson, but the rise of Oncorhynchus mykiss contains a bizarre and fascinating cache of insights into human motivations and misunderstandings.

In fact, as described in Halverson’s new book, An Entirely Synthetic Fish, the rainbow trout is—like corn—both biological instantiation and evolving allegory for our complex relationship with nature, our misguided interventions, and their unintended consequences.

In order to arrive at that conclusion Halverson explores a sequence of jaw-dropping, interlinked sub-stories, including the invention of artificial fish propagation, Congressional anxieties about American virility, aerial fish bombing, and migrating DNA, all of which have played a role in the rainbow trout’s journey towards world domination.

IMAGE: “Spawning Rainbow trout at a U.S. Fish Commission facility in Iowa.” From the National Archives, via Anders Halverson’s website.

IMAGE: “Steve Smith (Maintenance Mechanic) spawning rainbow trout. ca. 2005,” White Sulphur Springs National Fish Hatchery, from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Fish culturists apparently sometimes refer to themselves as “fish squeezers.”

Halverson picks up the story in the nineteenth century, when rainbow trout were “native only to the Pacific Rim from Mexico to Kamchatka.” One technical innovation and two cultural imperatives later, however, and the rainbow trout were well on their way. The scientific breakthrough came in 1843, when “a poor French carpenter and sometime fisherman named Joseph Remy and his friend Antoine Géhin” wrote a letter to a local official describing their technique for artificially propagating fish.

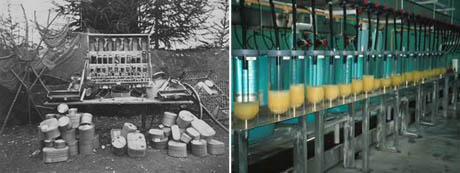

IMAGE: Hatching fish, then and now.

Prior to that, fish had been farmed in ponds, but they reproduced naturally. The method Remy and Géhin described is, according to Halverson, “essentially the same that is used today.”

During spawning season, at the beginning of November, at the moment when the eggs are loose in the belly of the trout, I have, by passing my thumb along and lightly pressing the belly of the female, so that it does not result in any harm for her, forced out eggs that I placed in a pot full of water. Afterward, I took the male, and with a similar operation as for the female, I made the milk run onto the eggs until the water was white.

By 1852, the French government had realised the significance of this discovery and built the first ever piscifactoire at Huningue. Remy and Géhin “each received a pension and a tobacco shop” as reward, notes Halverson, and just one year later, artificial fish insemination came to the United States when “an Ohio doctor named Theodatus Garlick read about the efforts then under way in France and decided to try the technique with native eastern brook trout.”

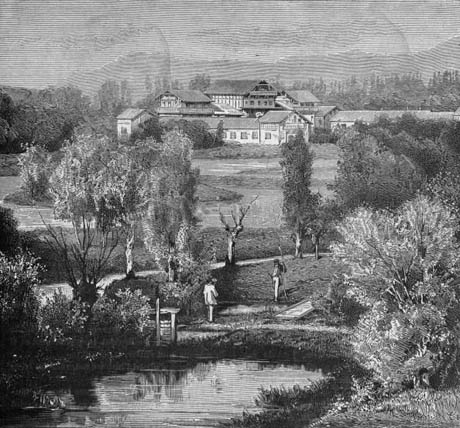

IMAGE: “Exterior view of the establishment of fish farm Huningue. circa 1860. Engraving from the book Album of science famous scientist discoveries in 1899″ (Photo by Apic/Getty Images)

At roughly the same time, a couple of other forces were at work, which together set the stage for the enthusiastic adoption of fish culture as a tool to breed and spread rainbow trout across the United States. Both were manifestations of a particular relationship with nature as well as responses to historical circumstance.

On the one hand, Halverson describes the acclimatisation movement, with its mission to transfer “useful” species throughout the globe. Grounded in a colonial and Christian mindset, in which nature existed as a resource to serve man and to be improved upon through his ingenuity, explorers from Christopher Columbus to Captain Cook had brought home tomatoes and left behind pigs.

By the nineteenth century, as explorers were replaced by settlers and the British and French invested heavily in the bureaucracy of empire, the first formal acclimatising group was founded: the Société Zoologique d’Acclimatation, launched in Paris in 1854. Americans were not immune to this impulse as they moved west—Halverson observes that “as a philosophy, acclimatization fit well with American ideas of progress and manifest destiny,” and quotes a common sentiment at the time: “Let the best fish, like the best man, win.”

IMAGE: “Starling Wave,” by Danny Green, Nature Black and White award winner, Wildlife Photographer of the Year in 2009, via. Halverson includes the infamous story of Eugene Schieffelin, a founding member of the New York chapter of the Acclimation Society of North America. His personal goal was to introduce every bird mentioned in Shakespeare to the U.S., and he achieved some success with the release of starlings in Central Park in 1880 (their first nesting site was under the eaves of the American Museum of Natural History). Since 1910, it has been illegal to import starlings, but the ban came too late—today there are an estimated 140 million starlings in the U.S., and they are now regarded as a major pest.

As it happened, many felt that the American West was “somewhat lacking” in fish fauna, and Halverson quotes Congressman Robert Roosevelt‘s bold declaration that:

There is no reason why the waters of the West should be less prolific than those of the East, provided the right species were introduced; and were trout, salmon, bass, shad, and sturgeon to take the place of catfish, pickerel, and suckers, the gain would be manifest.

The third coincident factor, and perhaps the most intriguing, is a pervasive anxiety that if American men were not able to go fishing, the national culture and values—even democracy itself—would somehow be compromised. Halverson speculates on several possible causes for this sentiment, from increased urbanisation (by the end of the nineteenth century, 33% of Americans lived in cities, compared to only 7% at the beginning) to the closure of the frontier in the 1890s. Whatever the cause, the second half of the nineteenth century was filled with laments for the “soft-muscled, paste-complexioned youth” with their “lack of nerve force” who were making America “a duller, as well as more effeminate” nation.

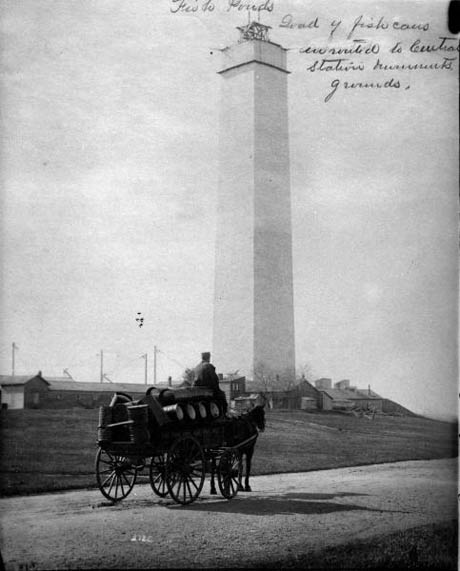

IMAGE: “Hatchery fish arrive in milk containers on a horse-drawn cart. Note the unfinished Washington Monument in the background.” The overlap between rainbow trout and national pride is clear in this photo from the National Archives, via Anders Halverson’s website.

The popular solution to this crisis of virility was to encourage outdoor activity, and in particular, hunting and fishing—”the sports of the field.” The problem was that, in the northeast at least, “human activities were rapidly diminishing the numbers of salmon, trout, and other fish in New England.” Since nothing could be permitted to stand in the way of progress, environmental regulations were not an option. Replenishing the streams with a steady supply of sturdier specimens was the only way Americans could continue to improve their characters by wrestling with nature even as their factories polluted the waterways. But which fish to farm?

The rainbow trout was the leading candidate. It had acclimated well, having proved that it “could also withstand much higher temperatures than the native trout of New York … a valuable trait in streams and ponds where excessive logging had turned once cool forest streams into sun-baked wastelands.” Rainbow trout were judged the equal of salmon and bass in taste, only slightly inferior in appearance, they hatched and raised well, and—most importantly—they were good fighters. As Halverson writes:

Because the character of the quarry was considered a direct reflection of the character of the pursuer, rainbows quickly became a favorite among sportsmen. “The man who has ever hooked a leaping fighting rainbow on light tackle in a canoe on the Soo Rapids will have all the thrills that should come to the honest fisherman,” opined one angler, “and if he wins, his manly chest is the proper place for the pinning of all the medals that are the reward of victory.”

IMAGE: “The U.S. Fish Commission raised fish for several years in ponds on what is now the National Mall in Washington D.C.” From the National Archives, via Anders Halverson’s website.

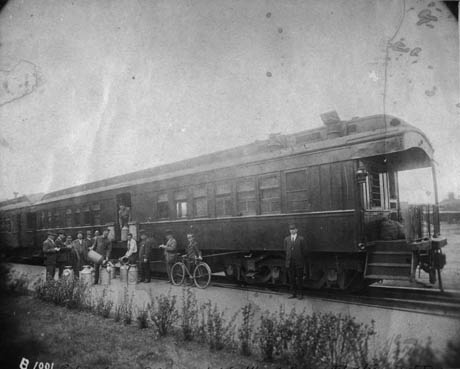

And so, in the interests of national security and progress, the U.S. Fish Commission was set up, and began assembling the infrastructure to propagate and distribute rainbow trout, from fish ponds on the National Mall to specially designed train cars.

For the next seventy-five years, dam-building policies and forestry economics conspired to serve the rainbow trout’s ends. Railway companies and agency officials collaborated in a supply and demand feedback loop, advertising where hatchery fish had been dumped so that weekend anglers could line up “shoulder to shoulder, yanking trout out of the water almost as fast as they could be poured from the truck.”

IMAGE: “From 1881 to 1947, the U.S. Fish Commission delivered fish to private as well as public applicants throughout the United States on specially designed train cars like this one. The cars had water tanks, aeration devices, cooling systems, and bunks for the attendants, among other things.” From the National Archives, via Anders Halverson’s website.

In one of the more surreal sections of the book, Halverson describes the origins of aerial fish-stocking missions, as surplus World War II planes and demobilised pilots were successfully redeployed in the 1950s to introduce the rainbow trout to previously fishless lakes, high in the California mountains. Even as you anticipate the disastrous ecological consequences, it’s hard not to be amazed by the gung-ho ingenuity of former crop duster and California Department of Fish and Game pilot Al Reese:

First, Reese tried freezing the fish in ice blocks and parachuting them in ice cream containers. Both of these techniques, though, proved dangerous and difficult. And so, one day, Reese and his assistants tried a simpler technique. They put fifty trout and some water into a five-gallon can and threw it out the window toward a hatchery pond about 350 feet below. They missed, and the can bounced along the rocks nearby instead. But when observers recovered the twisted metal debris, they found sixteen fish still swimming in the small amount of water that remained.

Ultimately, Reese and the team ditched the barrels altogether in favour of releasing fish that would hit the water “with a vertical speed of about thirty miles per hour,” in a scene described by observers as “a cloud of mist that suddenly appeared behind the plane, full of the barely distinguishable dark shapes of small fish.” Of course, sometimes the fish bombers missed, but nonetheless, aerial fish-stocking proved cheaper and more effective than other methods in such remote locations.

IMAGE: Aerial fish stocking, via.

IMAGE: Aerially stocked fish hit the water, via.

As you would expect, these experiments in the rational optimisation of one element within a complex ecosystem had unpredictable and frequently disastrous results. Some, such as the loss of amphibian life, were (until recently) perceived as unimportant if they were perceived at all, while others, including the mass poisoning of the Green River, in order to “rehabilitate” it by removing native fish and introducing rainbow trout, caused a scandal even at the time.

IMAGE: Rainbow trout restocking in California, via.

Meanwhile, raising a single species of fish in cramped conditions naturally served to increase pest and disease vulnerability. For example, Halverson reports that by 1987, a peculiar-sounding but nasty infection called whirling disease had contaminated hatcheries across Colorado, and by the mid-1990s, the disease had established itself in “thirteen of the state’s fifteen major river drainages,” with a predictable impact on fish numbers.

IMAGE: Fish with whirling disease, which causes them to swim in a corkscrew motion, via.

Perhaps the most interesting example of the inadequacy of human epistemological models combined with the law of unintended consequences comes towards the end the book, as Halverson describes the difficulty fisheries officials have in implementing any policy that requires the differentiation of native and non-native, now that the rainbow trout has interbred with other species promiscuously, spreading its “genetic pollution at a very rapid clip.”

IMAGE: A rainbow trout, via.

IMAGE: A westslope cutthroat trout, via. The westslope cuttthroat is a candidate for Endangered Species status.

IMAGE: The increasingly common “cutbow”—a hybrid rainbow trout and westslope cutthroat—via.

“Rainbow genes,” Halverson writes, “have become their own entity, disconnected from the fish in which they have began.” The result is a policy nightmare, with endangered species going “extinct due to such hybridization,” while experts consider whether “a fish can be considered a member of a species and a threat to the species at the same time.” Meanwhile, other scientists continue the re-engineering, adding an extra set of chromosomes to the rainbow trout “to make them grow faster and bigger,” and then feeding them creatine in an attempt to make them “harder fighting fish.”

IMAGE: An obese rainbow trout, the result of an extra set of chromosomes and some steroids, via.

To conclude his cautionary tale, Halverson reports that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Commission has now “distanced itself from the rainbow trout,” and that many states are now undertaking non-native “fish removal” programs (which are, of course, complicated by the hybridisation outlined above). On the other hand, he reports that fishing for hatchery rainbows is “one of the fastest growing sports around cities like Beijing.”

In any case, it’s almost impossible to do justice to such a complex and fantastically weird tale in a blog post, and I clearly can’t recommend An Entirely Synthetic Fish highly enough. It’s not simply a page-turning collection of fascinating stories, but an entirely new lens through which to understand 150 years of collaborative human/rainbow trout ecological, hydrological, cultural, and economic redesign—in which the rainbow trout seems to have had the upper hand throughout!

[Huge thanks to Geoff Manaugh for finding and giving me Halverson’s book!]