It’s A Tasty World – Food Science Now! is a special exhibition currently on display at the National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation (Miraikan) in Tokyo, Japan. The exhibition was designed by Assistant, an international & interdisciplinary design practice.

IMAGE: INABA’s design for Sandwiched at the Whitney Museum. Photos by Naho Kubota via Abitare.

Over a lovely lunch at the INABA-designed pop-up café, Sandwiched, at the Whitney Museum in New York City, Assistant’s co-founder, the multi-talented architect and artist Megumi Matsubara, discussed her exhibition design process and took me on a virtual tour of It’s A Tasty World‘s contents. The resulting conversation covers cutting-edge food science and creative visualisation techniques, while providing an interesting insight into what the future of food looks like from a Japanese point of view.

• • •

IMAGE: Quick iPhone photos of Megumi taken during our lunch at Sandwiched.

Megumi Matsubara: It’s quite unusual for this museum to have an exhibition about food. Normally they have exhibitions about things like genetics, or robotics, or nanotechnology – but actually all of these topics are relevant to food too. Still, to have an exhibition about food, even though it’s from the perspective of food science, was quite a big challenge for them.

Another challenge was that they wanted to cover everything about food from the perspective of science, not just agriculture or flavour science or one particular area. Our initial brief was a very thick, almost text-book size, printed-out pdf full of information. They said that they wanted to make that document into an exhibition.

It took us probably two or three months just to read it all through and digest it – partly because it was so many pages, but also because it’s about food, so you have some kind of knowledge about part of everything they are talking about, but at the same time you feel rejection towards certain facts and you doubt some of the things that they say. It was difficult to really absorb without preconceptions and prejudgment and things.

Edible Geography: What kinds of things were hard to accept or shocking to you?

Megumi Matsubara: For example, they included McDonald’s in the exhibition. They became a sponsor afterwards, but they were included in the contents from the beginning. We said, “Hey, come on, we’re not going do something about McDonald’s! Are you sure?” But the thing is, when we listened to the curators more, we gradually understood. What they focused on with McDonald’s is the quality control aspect of mass-produced food, and only that aspect.

McDonald’s food has to taste the same every time you have it, wherever you are. In a way, they are one of the most conscientious at maintaining this level of standards – so they are the best example to show this aspect of food science.

When we started understanding the way the curators were thinking about this, we accepted everything that they chose to put in the exhibition, whereas before we were going through saying, “No, not this part, and maybe we should have more organic food,” and so on. But actually, the curators tried to be as neutral as possible in terms of sticking to the point of view of science and innovation.

Edible Geography: This question of trying to look at food science and technology dispassionately without automatically deciding it is a force for good or evil was something that came up at Foodprint NYC. It’s easy to think that anything that takes us further away from brushing organic dirt off a carrot you just picked is bad, but then we ignore the possibilities that technology can afford us – and at the end of the day, cooking and pickling and salting and all of these traditional methods of food preparation and preservation are as much about chemistry and technology as astronaut ice-cream.

Megumi Matsubara: Exactly. This was definitely the point of discussion at the beginning, because our automatic reaction was to want to talk about organic food and urban agriculture much more – but then we came round to understanding the curators’ point of view.

IMAGE: It’s A Tasty World – Food Science Now! All exhibition photographs by Kenshu Shintsubo, unless otherwise noted.

Once the reading and understanding was over, the next step was figuring out how to visualise everything. In all of this huge pdf they gave us, they had just a few pictures – like, for example, a model of the brain showing where the regions involved in flavour and taste are. One day we were sitting down with them and talking about the exhibition, and we asked, “So, where is this model? When is it coming, and what size is it?” Because we were thinking that they had some objects to show. But they said, “No, there’s nothing – this is just an illustration.” So we said, “OK, well, what are you going to show?” And they said, “That’s up to you!”

So we had to take all of the information in the pdf and make it experiential. It was totally up to us to bring each aspect of the science to life. In this kind of emerging science museum, they don’t have actual objects like dinosaur bones and things. That’s something we really only realized after a couple of months, and once we did, we thought, “Oh my god, this is a lot of work.” We had thought the job was more like scenography – to create the atmosphere of the whole thing. But it was actually scenography and the creation of the exhibition contents.

We became a translator of stories into experience. We didn’t want to have an exhibition that was just panels full of text, so we turned as much text as possible into experiences – meaning tons of installations on different scales. We deliberately tried to create the feeling of a story like Alice in Wonderland. One step forward, you might feel you are bigger than life, while one more step would make you feel smaller, so that you can enjoy the process of restructuring the relationship between food and yourself.

It’s a 700m² exhibition, so it’s quite large, and the whole thing follows a storyline. Including the prologue, it’s divided into seven sections. One is about the biological mechanisms of taste, one is about the mass production of food, and another is food preservation. There is also a section on the future of food, a section on recycling of food and waste reduction, and the final section with some global context.

Menu 1: Mechanism of Taste

Megumi Matsubara: The red thing you can see is an overscaled tongue to explain the physiological mechanism of taste. It’s a dress that you can wear like a coat – it’s quite huge, and full human height. The curators had a really complicated graphic to explain the science of taste and I thought everybody would just skip it.

IMAGE: Red tongue dress by Tetsuya Yamamoto. Photograph by Danielle Demetriou.

Our idea was that people will think this coat-dress will be cool to wear, so they will put it on and then when they see themselves being part of the contents of the exhibition, they will get interested in reading the explanation.

You don’t think before you interact with things – but once you touch things, you ask questions about them and why they are a certain way, and then you can go deeper into the idea and maybe even read the text. We asked a very talented Japanese fashion designer (Tetsuya Yamamoto of POTTO) to design it, and he made it into this haute-couture-style super-beautiful coat with inlaid textiles on the back and things, so you could even wear it in normal conditions. It was really a beautiful dress.

We just sent him the scientific drawings and asked him, “Please design a dress.” We have a children’s size too.

Megumi Matsubara: There are five main tastes, and even babies can detect them. They have video footage of a week-old baby’s face when they sense each of the five different tastes – their face changes in a particular way. So we put the video screens in the baskets in a little box, one for each taste. It’s a consistent reaction pattern to each different taste. This one is sweetness. Sour, they go really like this [makes pursed-lip face]. It’s so weird. The sweet face is much more peaceful.

Megumi Matsubara: The curators wanted to talk about the relationship between the colours of food and flavour and appetite, so we made these roulettes that you can spin. Once you spin it, only the median colour will be extracted, separated from the individual variations and shapes.

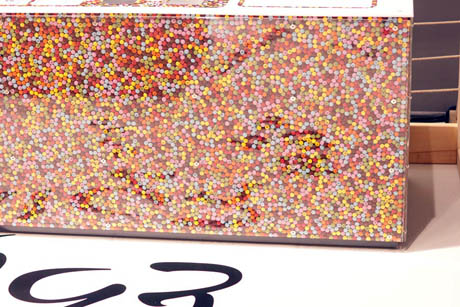

IMAGE: According to the exhibition’s curators, the melting temperature of cocoa butter varies based on where cacao beans are grown. The ratio of three different triacylglycerols changes in different production areas. As a result, “it is possible to adjust the feel of cocoa butter’s melting speed inside the mouth by blending cocoa butter that has different melting temperatures” – unless you’re making single-estate chocolate.

Megumi Matsubara: These are actually marble chocolates, like the M&M kind of chocolate. This section is about the physics of texture, and chocolate has a lot of innovation when it comes to texture: melting points and tongue-feel, and some have bubbles and different shapes. There’s a lot of physics going on there.

The curators wanted to show molecule models and some basic concepts from physics that you would have learned back in school. So we made tables with real chocolate, just to have the atmosphere of chocolate, because the science itself is quite serious, and not that fun – even though chocolate is so much fun, right? We wanted to have this juxtaposition of two things: the scientific content and the idea of chocolate. So the display tables are actually made out of real chocolate, with an acrylic surface at the top. Kids keep trying to put their fingers in from the side to get at the chocolates!

Menu 2: Delicious for Everyone! – Mass Production of Food

IMAGE: According to data from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, the food self-sufficiency rate in Japan is as low as 40%, meaning that “the majority of ingredients used even in washoku (Japanese cooking) are, in reality, imported.” Among the statistics, this one is particularly shocking: 61% of the farm household population is 65 years old or older.

Megumi Matsubara: These large numbers are showing the self-sufficiency of agriculture in Japan – how much of each type of food that Japanese people eat is produced inside Japan. One number could be for rice, and another for wheat, and so on. The numbers are quite scary – as low as 2% for some things.

Megumi Matsubara: This section is about 7-11’s POS (Point Of Sale) system, in terms of innovation in barcodes and inventory tracking. On the left is also a can – from Napoleon – blown up to see the structure, which is in the food preservation section.

Megumi Matsubara: These images are quite amazing factory videos – slicing onions, deep-frying, and all kinds of factory food processing. The images are beautiful and impressive and kind of scary. And, as I said, there was a whole section about quality control at McDonald’s. They have colour chips for lettuce, you know? So if a lettuce leaf is between shades one and three, you cannot use it. All the lettuce needs to be from colours four and five, or else you cannot use it.

Menu 3: Delicious Forever – Food Preservation Technology

Megumi Matsubara: This installation shows the same foods: one with preservatives and chemicals, and one without, so you can compare.

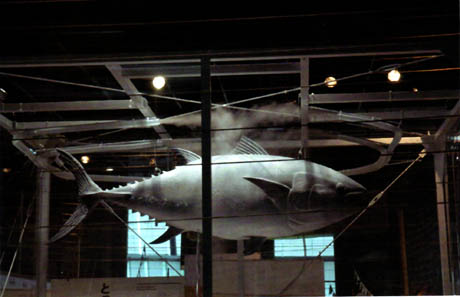

IMAGE: According to the exhibition’s curators, “it was only forty or fifty years ago at most that anybody was able to eat raw tuna sashimi, instead of the marinated ‘zuke‘ style. Refrigeration and freezing technology has changed our food culture.”

Megumi Matsubara: The big tuna is in the food preservation section too – it’s about the very basic but very impressive technology of flash freezing of big tuna. So we made the life-size tuna and made it look a bit frozen. We actually wanted to use a real frozen tuna, but the exhibition was running for four months and the scientists didn’t think it was advisable, so we just made a model of it and put it in a box with a chilly mist, so it looks frozen.

Megumi Matsubara: The stack of cans on the left represent a new structure for packaging. There is a patented way of folding called Miura-ori. This origami engineering technique was invented to make antennae that could unfold in space, but when it is used on aluminium food cans it allows a thirty percent cost and materials cut.

Megumi Matsubara: At the end of the preservation section, they show really fun footage of a Japanese astronaut eating space food. The technology of freeze-dried foods, which is based on Cup Noodles, contributed a lot to the development of space food. There is some other content on them too, but half the screens are just showing Cup Noodles eaten by different people in different locations, to make a contrast to the space video. One of them shows my studio partner eating Cup Noodles in the park and another shows kids eating it on a bicycle. It’s like space technology in everyday life.

Menu 4: What is the next “Delicious?” – Food of the Future

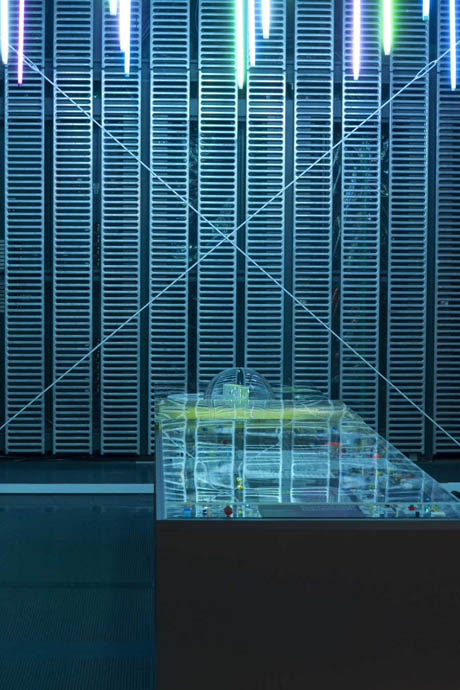

IMAGE: Euglena is a single-cell microbe known as midorimushi in Japanese. The exhibition’s curators describe it as follows: “It has the ability to carry out photosynthesis, which brings in CO2 and produces oxygen. As it has no cell wall containing cellulose, it can be easily digested and absorbed into the human body. It was originally researched as a supply of oxygen and food for astronauts, but it also may be effective for solving our food crises here on Earth.”

Megumi Matsubara: This section is about essential nutrients, and what your body needs to survive. At the bottom of the glass structure are all kinds of supplements and vitamin pills in different combinations, to communicate the idea that the human body needs different nutrients in different combinations from a variety of sources – there is no ideal meal in a capsule form like in the dreams.

At the top is Euglena: it’s an edible insect that is living in water. I think you can find it anywhere. It’s greenish, and you need a microscope to be able to see it really. It is the most recent discovery of a food that is easy to increase and provides all the nutrition we require, so the curators ask whether this is the future of food – but they also set it alongside all the pills and supplements that have been called the future of food in the past.

Megumi Matsubara: This section is partly designed to allow you to sit and relax on tatami mats in the middle of the show!

Actually, you can also learn about manners and food etiquette at the same time. The video shows how to eat according to traditional Japanese manners. I love this video – it’s so much fun. The idea is that future foods might lead us to abandon traditional manners – so they wanted to show what those are, to raise the question about what the manners of the future will be.

Menu 5: After Eating Deliciously – Problems of Food Disposal

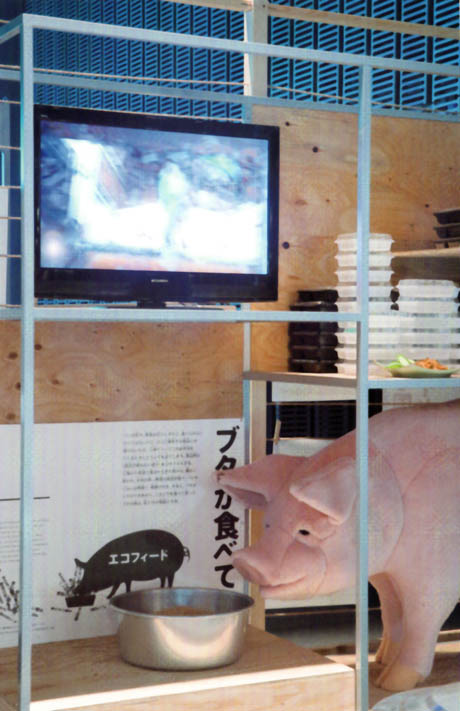

Megumi Matsubara: This is called Ecofeed (pdf). Convenience stores make lunchboxes in factories, and when they are cutting the bread and vegetables and things, they have some food scraps and crumbs leftover. They dry those scraps and feed them to pigs, and then pig manure feeds the soil, and then they grow radishes in the soil, and the radishes and pork go back to the factory to be part of the 7-11 lunchbox.

IMAGE: According to a 2005 Ministry of the Environment report, each Japanese person creates 12.4kg of food waste per month.

Megumi Matsubara: This installation is about new research into producing energy from food waste by creating ethanol, rather than just burning it. To explain that we built these garbage bins – these are like ordinary street garbage bins that you can find in Japan, although normally they are not in the shape of houses. The idea is that you can connect this with your everyday household garbage. We put lights inside them that visually show that you can produce five times more energy with the ethanol process than by simply burning the food waste.

Menu 6: Is It Really “Delicious”? – Health/Safety/Food Crisis

Megumi Matsubara: Finally, we’re at the end, and we start talking about people’s fears and beliefs about food. These panels are about food faddism. You see common claims and beliefs on the other side, and facing us are the answers. For example, some people think that eating onions will make your blood run smoother, but actually if you want to experience that effect, you have to eat 50kg of onions a day. Of course, what you believe is what you want to believe, but from the scientific perspective, these claims can’t be true.

We also built 60cm tall milk cartons, to show what size they would have to be to fit every single bit of nutritional information that scientists know about milk onto its packaging. People want and need more information about their food, but what’s useful and what’s not?

Megumi Matsubara: That totem with the plant growing out of the top is actually about MSG (monosodium glutamate). It’s an extract of sugar cane. A lot of people have mixed feelings about MSG – Europeans don’t like to eat it, and I thought it was actually harmful. But then this totem explains how it’s made, and shows that it is 100% made of natural ingredients. The process is chemical, of course – if you’re extracting molecules, that’s scientific. It’s up to you still if you want to use it or not, but it is extracted from natural products, so the question is about what is natural and what is not, and whether “natural” foods are always safe.

They also use the example of mad cow disease to ask where the limit should be. How far should science go? What’s safe? What’s healthy? Science can show what’s possible, but after that, it’s up to people to decide what it’s okay to do. Then, in the final corridor, there are lots of maps – hunger maps, food production maps, and so on – to give the big picture. Because in the end, good-tasting food is both biological and psychological, and the curators wanted to end with questions – like, what is real tastiness, in this context?

We ended back where we began the design process, actually: everybody has their own philosophy and their own feelings about food, because it’s so close to you and to your life, and so it’s hard to be open-minded and just think about the science. Meanwhile, the museum’s concern from the start was to talk about food in scientific terms, without all that rich context of philosophy or culture – but is that possible or even a good thing?

That’s one reason they wanted to partner with us, to add back the human connection and experience that is so important in the topic of food. We gradually realised that our role is to put this unwritten element into the exhibition, to give some context for the science. They wanted to make sure everybody left the exhibition not just understanding innovation in food science, but feeling that their relationship with food is really important.

In the exhibition, you can touch everything, and we didn’t build any walls. We just used rope to separate the space because we didn’t want anything to stand in between people and food, and the different ideas of food. It’s all one landscape.

Also, even though there is so much science and technology included, even just at the level of projections and moving images, we deliberately used only simple cotton fabrics and patchworked fabrics for the signs. Everything is just hanging, pinned up with clothes pegs.

All the letters are made of felt and handcrafted. Even the staff at the museum embroidered for us! We knew we wanted to make the main signs hand-embroidered, but it’s a lot of text, especially in the Japanese alphabet. The production company couldn’t find anyone to do it, so finally the museum staff did it – everyone did three lines. I think it’s really, really nice, because it embodies the time that goes into preparation and handcrafting, and that’s an important aspect of food too. Even though it’s not explained in the exhibition, people can feel it because of the density of the time that has been spent, and the richness of the textures. So that’s a way to communicate something the text doesn’t say – because the way the text is made is all about that philosophy.

• • •

It’s A Tasty World – Food Science Now! is on display at the National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation (Miraikan) in Tokyo, Japan, until March 22. Let me know if you get to see it in person, as I’m afraid I won’t be able to, sadly. It sounds well worth the trip!

I’m very grateful to Megumi Matsubara for giving me such a detailed and fascinating remote tour – and to David Garcia for allowing me to hijack our lunch!