IMAGE: Still from Talking Nose video. All images courtesy Sissel Tolaas, unless otherwise credited.

Artist Sissel Tolaas was one of the people I most wanted to speak at Postopolis! DF, having seen her discussing smell as design in New York earlier this year. Although she was not able to join us in person, she generously allowed me to screen her olfactory investigation of Mexico City, Talking Nose — which was also the first time the video and soundtrack had been seen and heard in the place where it was made.

IMAGE: Still from Talking Nose.

Tolaas is half-Norwegian, half-Icelandic, and lives in Berlin. Her artistic practice explores olfaction — the sense of smell — by working with the odor molecules that our noses detect and the language we use to describe them. She first became interested in smell twenty years ago, as an outgrowth of art projects related to weather, the atmosphere, and its ingredients. As she explained to Mono.Kultur magazine, whose most recent issue was devoted to her work (to the extent that its pages are impregnated with several of her smells, making it hard to read in public!):

In the beginning […], I created weather situations that didn’t exist. I was trying to provoke people to talk about the weather in a different way. So I created these situations in my lab or in my flat where you had sunshine or explosions, hurricanes… It was during these experiments that I discovered smell.

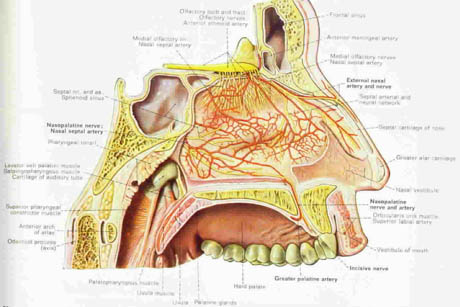

IMAGE: Anatomy and physiology of the human nose, via.

Our sense of smell is both fundamental and neglected. As Tolaas pointed out to me in an email, every time we breathe, we inhale smell data, and “each day we breathe about 23,040 times.”

Yet as a means of experiencing, describing, and designing the world, sight, hearing, taste, and even touch seem more influential — perhaps in part because, amazingly, no one actually understands how the sense of smell works. There are compelling theories, but the exact way in which the brain detects and decodes odorant molecules is still a scientific mystery.

IMAGE: Sissel Tolaas on a smell walk.

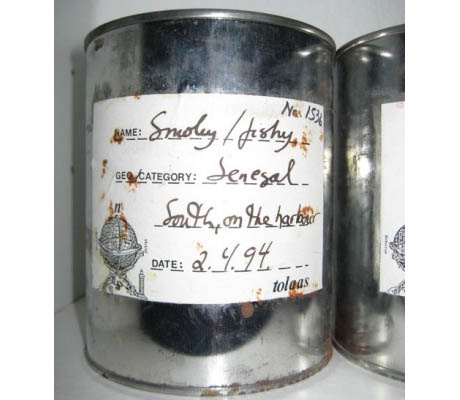

Tolaas began training her sense of smell in the early 1990s, collecting bits and pieces — swatches of fabric, bits of food, crayon stubs, banana peels — that held a specific smell, and archiving them in a personal odour library of 6,723 airtight tins. She used this archive to train — to sharpen her olfactory acuity and to breakdown her smell prejudices, so that she could approach smellscapes without the distraction of disgust. She’s also been training her teenage daughter, Tara, since birth.

Following on from odor gathering, Tolaas drew on her chemistry background to move into smell analysis and recreation. Somewhat magically, scientists at the major fragrance and flavour companies have developed so-called “headspace technology,” which allows them to capture any smell in the world by enclosing it in a vacuum-sealed jar with odour-absorbent paper, cloth, or gels. The material is then broken down into a molecular ingredient list using mass spectrometry or gas chromatography, so that it can be rebuilt in the lab from off-the-shelf chemicals.

IMAGE: Sissel Tolaas’ smell archive is stored in 6,723 airtight tins.

IMAGE: Every smell in Tolaas’ archive is labeled with the date and place it was collected. Photo via Sight Unseen.

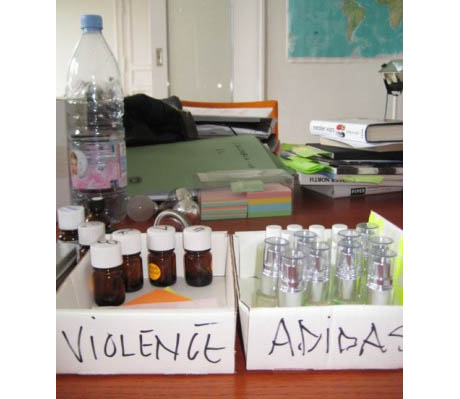

Givaudan or IFF might use headspace technology on jungle treks to sample the rare blue lotus or capture the fragrance of previously unknown orchid varieties. Tolaas’ uses vary: she has created “Swedish smells” for Ikea and Volvo, and is currently working on a suite of brand identity odours for Adidas but has also recreated the smell of a battlefield for the German Museum of Military History in Dresden.

IMAGE: Headspace technology used in the field by Roman Kaiser, chemist, botanist and perfumer at the Givaudan fragrances and flavours company. Image courtesy Givaudan, via Time

IMAGE: Current projects in Tolaas’s lab space. Photo via Sight Unseen.

I first encountered Tolaas’ work at the Louisiana Museum of Contemporary Art in Denmark last summer. To make her piece, Fear 9, Tolaas asked nine highly phobic men to wear a sweat-collecting device “the size of a cell phone” under their armpit while exposing themselves to the situations they most feared. They then mailed the sweat (overnight delivery) to Tolaas’ lab, where she chemically analysed it, recreated it, and then used micro-encapsulation technology to turn the Louisiana gallery wall into a giant scratch and sniff embodiment of fear.

The nine men’s smells (which you can also experience in Mono.Kultur) vary in intriguing ways, and elicited equally interesting responses: Tolaas explained that Guy #9 was very popular, particularly with one woman who “came every day for three months and kissed the wall up and down with different lipsticks.” (Number 9 was definitely my favourite too: spicy and light, where the others were pungent, rancid, and gym locker-ish.) Meanwhile, Guy #5 brought a ninety-year-old Korean war veteran to tears, taking him back to the battlefield in a visceral yet cathartic way. Tolaas gave him a small vial of the scent to take home.

IMAGE: Fear 9, by Sissel Tolaas.

Tolaas has even used headspace technology to distill and recreate the smell of money for a major bank — and, although she does not use perfume or deodorant, she will sometimes wear a drop of that to a business meeting, where it seems to guarantee positive results. She also wears her own smell — extracted, recreated, and applied in concentrated form — as both cologne and identity-reinforcement:

When I reproduce my own sweat and put it back on my own body the intellectual and psychological reaction I have to that, to my self, is just unbelievable. It’s fantastic. I rediscover myself as a human being.

IMAGE: Sissel Tolaas creating smells in her Berlin lab.

In contrast. Americans collectively spend $1.7 billion each year on antiperspirants and deodorants to mask their personal odour. The West is “smell-blinded,” according to Tolaas, who argues that “in modern Western culture, the topic of smell is repressed and its social history ignored.”

In his 2005 essay, Towards A Sensorial Urbanism, architect and author Mirko Zardini extends Tolaas’ diagnosis of smell-suppression to the spaces and cities we live in:

City planning has long privileged qualities of urban space based exclusively on visual perception. Above all, […] odours have been considered disturbing elements, and architecture and city planning have exclusively been concerned with marginalizing them, covering them up, or eliminating them altogether.

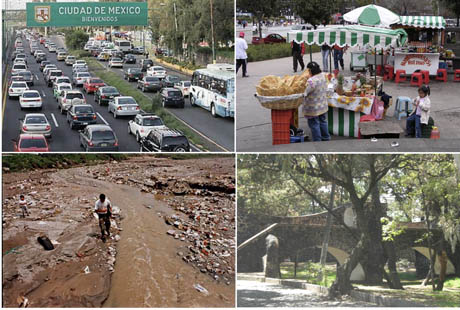

IMAGE: Mexico City’s varied smellscapes.

Tolaas’ own interest in the spatial effects of olfaction has led her to explore the smellscapes of different cities, from Paris and Vienna to Kansas City, using structured walks, interviews, and headspace technology. She explains:

Just as society is crisscrossed with symbolic and actual smell boundaries, so is the urban environment. The different smell spaces of the modern city are largely a product of zoning laws. These laws regulate the kinds of construction and sorts of activity that may go on in the different areas, and by so doing also regulate the distribution and circulation of smells.

Tolaas’ work, however, goes beyond simply mapping or recreating a sensory geography, into an investigation of smell as information — information that, if it was broadly shared and understood, could “play a role in communication and navigation.” To that end, she also researches the limited language with which we describe smell, in an attempt to move beyond preference (“good” and “bad” smells) and analogy.

In one experiment, she asked volunteers to smell two jars filled with the same relatively neutral air. Proving that verbal expectations can create olfactory illusions, they consistently reported preferring the jar labeled “cheddar” over the one labelled “body odour,” regardless of the fact that the sampled air smelled of neither.

IMAGE: Mexico City’s smog layer.

In Talking Nose, the project that we invited her to present at Postopolis! DF, Tolaas was inspired to investigate Mexico City’s smellscape by its notorious pollution:

In Mexico City, you can cut the air with a knife. But bad smells simply are not noticed any more. Imagine if this technique were carried over into the other senses and eyesores were made invisible or the noises of construction and traffic inaudible. Half of the sensory reality of our cities would vanish. Apart from the likely problems of safety, we would lose our ability to experience the environment we live in and react to it according to that experience.

Beginning in 2001, she began to study Mexico City in terms of the chemical signals in its environment, visiting more than two hundred different neighbourhoods repeatedly in order to research and identify the key smells of each. Using headspace technology, she then re-presented those smells in a scratch and sniff map of the city.

IMAGE: Talking Nose as installed at Harvard in 2009.

IMAGE: Talking Nose as installed at Harvard in 2009.

Meanwhile, Tolaas also filmed 2,100 Mexico City residents as they described the smell of the city and its atmosphere in their mother tongue. Alongside the scratch and sniff map, she presented a video of their noses, sniffing, and mouths, silently translating the invisible city, as well as — separately and deliberately out of synch — an audio track of smell descriptors: “rusty, sweet and old,” “pleasant, aromatic, light,” and “perfume-y; flowers, and vanilla.”

Presented together, the smells, the map, and the words, combined with looping video footage of chilangos smelling and describing, effectively reframed the experience of Mexico City in olfactory terms.

IMAGE: Still from Talking Nose.

What’s more, according to Tolaas, when she asked Mexico City’s inhabitants to use their nose to perceive the city, many of them associated themselves and their activities with the smells (and pollution) they described. Several of them, it seemed to her, were making that connection for the first time, exactly as she had hoped:

Challenging people to use their noses gives them new methods to approach their realities; it doesn’t matter whether they smell a so-called bad or good smell. What counts is that they rediscover their own surroundings in that very moment—be it other human beings, places, the city — and start to approach it differently.

IMAGE: Tolaas’ scratch and sniff map of Mexico City.

IMAGE: Still from Talking Nose.

[NOTE: This post is part of a series of reports from my time in Mexico City as part of Postopolis! DF, which was presented by Storefront for Art and Architecture from June 8 to June 12, 2010. For more about Postopolis! DF, including my fellow bloggers, their speakers, and the sponsors and organisers (to whom I am very grateful), visit www.postopolis.org. My sincere thanks are also due to Sissel Tolaas, who scrambled to get her materials to me in time, and to the fabulous Paola Antonelli for the introduction ]