IMAGE: Front cover of Life at Home in the Twenty-first Century: 32 Families Open Their Doors, by Jeanne E. Arnold, Anthony P. Graesch, Enzo Ragazzini, and Elinor Ochs.

Between 2001 and 2005, an anthropologist, two archaeologists, and one photographer conducted a detailed observation and visual enthnography of the material culture of thirty-two middle-class Los Angeles households. The researchers, based at the Center on Everyday Lives of Families at UCLA, set out to explore how American families interact with their houses, yards, and, above all, with the mountain of stuff that they acquire:

Marketers and credit card companies record and analyze every nuance of consumer purchasing patterns, but once people shuttle shopping bags into their homes, the information flow grinds to a halt. How do people interact with these material objects in everyday life? Which objects do they find meaningful? Are Americans burdened by their material worlds? Which key spaces inside the house serve as the main stages on which U.S. family activities unfold?

After five years of field observation, the team built up an archive of 20,000 photographs, 100 videos of narrated home tours, 32 detailed floor plans, and thousands of what they call “scan samples”: a record of each family member’s location, behaviour, and the objects they were using, taken at ten-minute intervals.

IMAGE: The CELF team found that the kitchen was the most-used room in the house, hosting homework, bill-paying, and daily planning activities in addition cooking and eating. Photo: CELF.

Their new book, Life at Home in the Twenty-first Century, which I discovered via culinary historian Rachel Laudan, pulls out and illustrates some key themes from that mountain of data — many of which have to do with cooking, eating, and storing food.

The statistic that catches Laudan’s eye is that when families in the study cook weekday dinners from fresh, rather than pre-packaged, ingredients, it takes only ten to twelve minutes longer, on average, than preparing a convenience-food meal. This is surprising, because most of the parents in the study cite time scarcity as the reason they rely on frozen pizza, boxed macaroni-and-cheese, canned soup, microwave dinners, and the like for two-thirds of their family’s weeknight meals.

IMAGE: One of many images of overfilled freezers in the book. Photo: CELF. Apologies for the scanning artifacts.

So why is making a meal from scratch perceived as taking much more time than it really does? The reason, the researchers explain, is to do with the additional mental effort required:

Perhaps the most important and clear-cut effect of packaged foods is that they reduce the complexity of meal planning. Dinners centered on convenience foods require less shopping and planning time since many separate ingredients do not have to be assembled. The family chef can invest less time thinking about the week’s meals. […] Frozen foods require less advance planning and less cooking knowledge and skills than acquiring and working with raw ingredients to assemble a dinner.

As Laudan notes, it’s obvious, yet revelatory: the real convenience offered by convenience foods is the removal of decision-making in a food environment that has never been so overwhelmingly filled with choices.

IMAGE: A high-density refrigerator door. Photo: CELF.

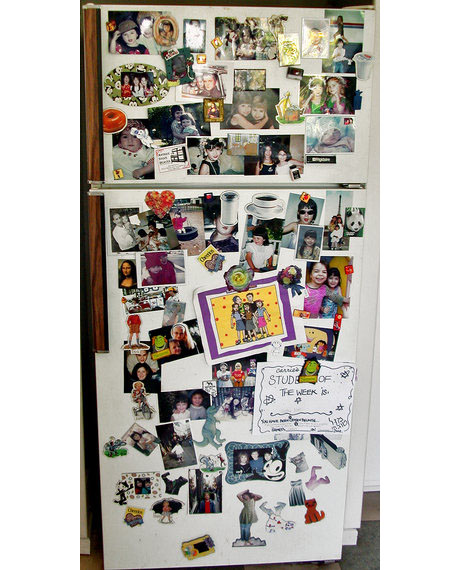

From my own refrigeration-obsessed point of view, perhaps the most interesting observation was the correlation the researchers observed between fridge door displays and household clutter. The refrigerator door functions as a kind of domestic command centre for most of the families in the study, displaying schedules, phone numbers, reminders, prescriptions, invitations, coupons, and take-away menus as well as family photos and souvenir magnets.

The average Los Angeles refrigerator door, the researchers found, “contains a mean of 52 objects, which consume up to 90 percent of the surface space,” although there is considerable variation — the family with the most extensive refrigerator display has managed to attach 166 objects to its front and sides. What’s more, it turns out that you can predict “how intensively families are participating in consumer purchasing and how many household goods they retain over their lifetimes” purely based on their refrigerator display style and density:

The look of the refrigerator door hints at the sheer quantities of possessions a family has and how they are organized or arranged in the house. By organization, we mean visual impact, which is a function of both the density and the neatness of the distribution of objects. A simple analysis using our coded material culture inventories reveals that a family’s tolerance for crowded, artifact-laden refrigerator surface often corresponds to the densities of possessions in the main rooms of the house.

Previously on Edible Geography, we’ve examined photographs of refrigerator interiors as portraiture; this finding implies that their exteriors can serve as a visual stand-in for domestic decor.

IMAGE: Another high-density refrigerator door. Photo: CELF.

Elsewhere, the researchers explore the phenomenon of food-stockpiling, noting that forty-seven percent of their families keep second fridge/freezers, and nine percent actually have a third one, stuffed with overflow supplies of beer, soft drinks, and frozen foods.

Meanwhile, scan-sampling logs found that even fewer Americans eat dinner together than say they do, with nearly one quarter of families never dining together over the course of the entire study. Forty-one percent of all dinners were what the researchers call “fragmented,” with family members eating sequentially or in different rooms.

IMAGE: Scan-sample map of family 11’s locations as observed every ten minutes over the course of two weekday afternoons and evenings. Image: CELF.

The book is filled with these sorts of details, extracting the extraordinary patterns and paradoxes of ordinary American domestic life. For example, despite Los Angeles’ perfect weather, and the importance of the backyard to the American dream, more than half the families in the study spent zero time in their yard during field observations.

The chapter titled “Material Saturation,” which enumerates the sheer quantity of stuff visible (i.e. not stored out of sight) in the families’ houses, offers the book’s most voyeuristic thrills, as photo after photo shows toys spilling across every surface, dirty laundry piled in a spare shower cubicle, and home offices drowned in a sea of miscellaneous objects.

IMAGE: Clutter. Photo: CELF.

“The United States,” the researchers write, “has 3.1 percent of the world’s children, yet U.S. families annually purchase more than 40 percent of total toys consumed globally.” The resulting chaos is enough to induce a vicarious nervous breakdown.

Indeed, in their conclusion, the researchers point out that while the incredible material abundance they observe “signals personal pleasure and economic success, it also entails hidden costs,” noting that consumerism is connected to most of the major trends their study tracks: “waning outdoor leisure time, unprecedented and often burdensome clutter, reduced social interaction at mealtimes, clashing schedules, the invasion of kids’ material culture into all corners of the house, stockpiling, and more.”

As an archaeology of the present, Life at Home in the Twenty-first Century is undeniably fascinating. As a minutely observed portrait of a particular way of life, it offers valuable insights — but also pause for reflection.