IMAGE: “Beiti” (detail from a 2011 installation at CAPC in Bordeaux, France), Laurent Mareschal. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Marie Cini. Photo by Tami Notsani.

IMAGE: “Beiti,” Laurent Mareschal, installation shot at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

Laurent Mareschal’s “Beiti” is a carpet made of spice, carefully sieved through stencils into tiled patterns inspired by Arabic geometry. I saw it last month at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum, on display as part of the Jameel Prize shortlist of Islamic-influenced contemporary art, craft, and design.

In the exhibit’s low light, the carpet seems to float above the black floor, warming up its corner with a slightly fuzzy glow and a faint gingery, spicy scent. In an accompanying video, Mareschal, whose work typically deals impermanence and, in particular, the Palestinian condition, explains that the spice tiles are a deliberate play between ephemerality and the almost subliminal longevity of olfactory memory.

“I want people to look and think […] wow, this guy is completely nuts, he has been working for a week and it will just vanish in a second,” Mareschal said, before adding that:

There is something about the smell that you can’t really refuse. It gets inside of you and makes you remember something. You can play with the colour and the smell and what it makes you remember and I am playing with that.

IMAGE: “Beiti” (detail from a 2011 installation at CAPC in Bordeaux, France), Laurent Mareschal. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Marie Cini. Photo by Tami Notsani.

With its Proustian olfactory powers, capable of transporting exhibition viewers to a remembered or imagined romantic Orient—a Moroccan souk or Egyptian spice bazaar—Mareschal’s spice carpet is perhaps also something of a magic carpet, that standard device of Eastern storytelling.

But the installation also reminded me of Paul Freedman’s fascinating book, Out of the East: Spices and the Medieval Imagination, which examines the incredible popularity of nutmeg, clove, pepper, cinnamon, and ginger in Europe during the Middle Ages—and their sudden fall from fashion in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Curiously, while their mysterious Oriental origins formed part of the allure of spice for European consumers, Freedman notes that, “alone among the great world religions, Islam has consistently resisted the use of incense in both public and private worship.” Meanwhile, for their Christian consumers, the uses of aromatic spices went beyond food flavouring and medicinal tonic to become a sort of medieval air freshener:

It was customary that the rooms of a comfortable house should be not merely airy and unscented but redolent of actual healthy scents from spices that might be scattered about or resins that were burned as incense.

Rooms were perfumed with spices to promote health (“Avicenna, the authoritative Arab physician whose work was known in Christian Europe by the late twelfth century, recommended that ambergris, frankincense, cloves, and even theriac be employed to dry out the air and make it smell sweet,” writes Freedman), but also for spiritual and aesthetic reasons.

As Freedman explains, the theological consensus at the time was that the Garden of Eden was located in eastern Asia, most likely in India. For medieval Europeans, exotic aromatics thus literally represented the scent of earthly paradise—a prelapsarian idyll of intoxicating beauty and freedom from decay.

IMAGE: “Terre Promesse 2” (detail from a 2008 installation using za’atar and cumin), Laurent Mareschal.

Of course, Freedman points out, it was this passion for spices that launched Europe on its path to overseas conquest and colonialism. The great expeditions of Vasco de Gama and Christopher Columbus were motivated by the desire to control the lucrative spice trade by finding and conquering its Asian source. The irony is that, by the time Europe’s colonial expansion truly hit its stride in the nineteenth century, spices had long since fallen out of fashion, all but disappearing from the continent’s cuisines.

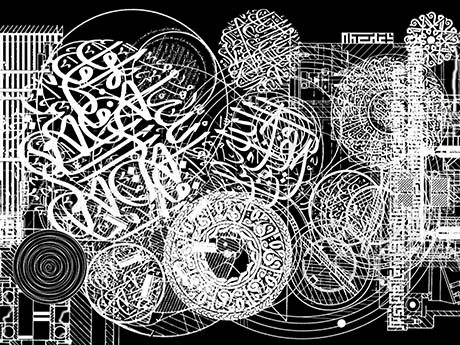

IMAGE: “Modern Times: A History of the Machine” (detail), Mounir Fatmi, 2010–12, (video). Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery, photo by Mounir Fatmi.

In any case, the Jameel Prize exhibition is on display at the V&A until April 21, and is well worth a visit if you’re in London. Florie Salnot’s plastic bottle jewellery, the mesmerising calligraphic gears and cogs of Mounir Fatmi’s video projection, and Faig Ahmed’s pixellated rugs are some of its other, non-edible, delights.