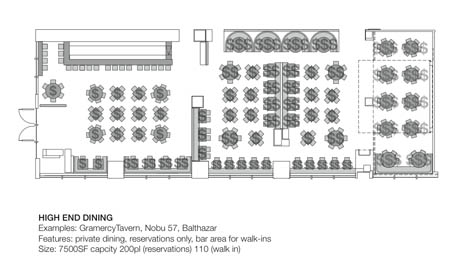

IMAGE: Drawing by Will Prince for the New City Reader Food Issue; data supplied by Marion Emmanuelle of award-winning restaurant designers AvroKo.

Stuck in a rut, and with his thirtieth birthday imminent, Paul Carr, the son of hoteliers, escaped it all by spending a year living in hotels. Somewhat predictably, his experiences led to a publishing deal, and the resulting book, The Upgrade, is excerpted in today’s Observer.

After noting that such semi-permanent hotel dwelling was once relatively common (apparently, nearly three quarters of New York’s upper and middle classes called a hotel room home in 1856), Carr explains that long-term hotel living, done right, can cost less than a year’s rent on a London flat. In his informative introduction to getting the best deal out of the hotel business, he points out that “a hotel bedroom is a highly perishable commodity — if it hasn’t been sold by the end of the day, it’s gone forever.”

Of course, this insight also holds true for a restaurant table (and an opera ticket, an airline seat, and so on).

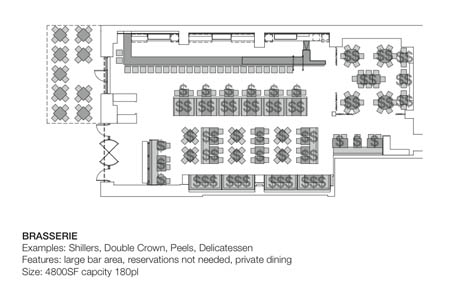

IMAGE: Drawing by Will Prince for the New City Reader Food Issue; data supplied by Marion Emmanuelle of award-winning restaurant designers AvroKo.

In other words, each spot on an eatery’s stain-resistant leather banquette has a shorter shelf-life than a perfectly ripe peach, its revenue-generating potential transmuted into financial drain every minute it remains unoccupied. Seen in this light, the restaurant floor is a terrifyingly volatile property market, packed with listings whose half-lives clock in at an hour or less (even high-end restaurants frequently expect to turn tables once during the dinner shift).

The particular economic logic of the dining table market is, of course, written into a restaurant’s business plan. As Alan Stillman, the founder of T.G.I. Friday’s, explained in our conversation last November:

The restaurant business does come down to real estate, though. A restaurant owner is renting or sub-letting you a piece of real estate for the evening, and how long you sit there and how much you spend determines whether they’re going to be successful or not.

Indeed, the space/time value of each dining chair can be calculated to the penny. A recent survey by lastminute.com found that every five minutes of seat occupancy at London restaurant Hakkasan carries a price tag of £6.17, for example, while the same rental period at Midsummer House in Cambridge costs £5.80 a head.

Although much restaurant design writing focuses on fashions in décor and lighting, from taxidermy to Edison bulbs, a dining room could thus perhaps be more accurately read as a landscape encoded with invisible information, its contours shaped by local health codes, server use-paths, and financial fluctuations.

New restaurant reviews could include a handy by-the-meal seat rental calculation alongside their descriptions of the chalkboard menu; in addition to nominating signature dishes, critics could recommend tables based on both value for money and traffic flow. If house prices were the standard dinner party conversation topic of the twenty-first century’s first decade, perhaps seat rental will be the restaurant chit-chat of the next…