IMAGE: Bordeaux-style wine bottles, available from Silver Spur Corporation.

A couple of weeks ago, one of my favourite artists, Luke Jerram, tweeted: “Just commissioned to design a new red wine bottle. Fun and challenging. Any ideas?”

Well, yes. My idea was to interview him, twice: at the start of the bottle design process; and then again, later, when the final product is ready to be unveiled. Excitingly, Jerram generously agreed to my suggestion, and even offered to share drawings and photos along the way.

IMAGE: A street piano in Sydney, Australia, from the “Play Me, I’m Yours” website.

Many of you will have encountered Jerram’s work already, through his wildly successful “Play Me, I’m Yours,” which has installed more than 700 pianos on the streets of thirty-four cities. I first discovered him through his wonderful hot-air-balloon-powered dawn chorus, “Sky Orchestra,” and then, while I was working on Landscapes of Quarantine, his eerily beautiful glass virus and microbe sculptures, so I’m thrilled to finally have a wine-bottle-shaped pretext to interview him for Edible Geography.

An edited transcript of our first conversation appears below; check back in the coming months to see how Jerram’s bottle design develops.

IMAGE: Part of Jerram’s “Sky Orchestra” over Stratford; photograph by Chip Horne, RSC.

Luke Jerram: The commission comes from a really interesting chap called Ruggero Ama. He originally contacted me about buying Aeolus, my giant singing sculpture. We’ve had an interesting dialogue about this new winemaking business that he’s developing in the Veneto region of Northern Italy. He’s making a type of red wine called Amarone, which has an unusual history — apparently it was first made by mistake, when someone left grapes in a basket and forgot about them for a couple of months.

Even the name of his company — Pipai — has a really nice story to it as well. It’s the nickname that Ruggero’s father used to call him, and it means “little cork” in the dialect of Ferarra, where he was born.

IMAGE: A Pomerol wine bottle, via Wikipedia.

In any case, he liked my glass sculptures, so he basically asked me to apply my creativity to designing some wine bottles. Originally, I was thinking, “Oh crikey, designing a wine bottle that’s going to be produced in the thousands is quite difficult.”

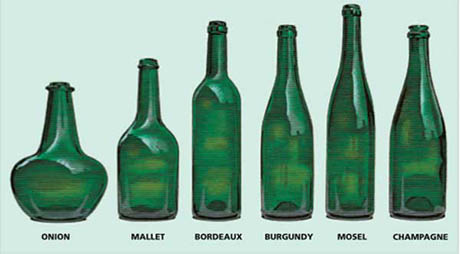

If you start looking into the history of the wine bottle and how it functions, a wine bottle looks as it does for all sorts of interesting reasons. You can read all about it on Wikipedia. For example, an ordinary wine bottle has got that little dimple at the bottom, which is there for reasons to do with pressure and channeling sediment. Obviously, you’ve got to put a cork in the top, under pressure, so you are talking about something that has to be quite sturdy. Then the curve of the shoulders is designed to collect any sediment as you’re pouring it. And, of course, the bottle’s got to be a certain strength for storing and for transporting. I’ve even read that the size, 750 ml, is roughly the average exhalation volume of the human lungs.

So a wine bottle — a standard wine bottle — is quite specific. Luckily, Ruggero doesn’t want me to redesign that. It’d be like redesigning the wheel. What he’s asked me to do is design something like a limited edition of, say, ten bottles, as a special thing that he could give to his investors or to friends and family, or put up for auction, or something like that.

IMAGE: A Bocksbeutel, used for wines from Franconia in Germany, via Wikipedia.

Edible Geography: Are you planning to design a single bottle and then fabricate it in an edition of ten?

Jerram: I think that’s the idea. Alternatively, you know, I could create ten different bottles that come together to form something. They would each be individual sculptures that, when they are together, turn into something else. There are all sorts of opportunities — it’s quite fun, really.

I suppose this is what I do — I spend a lot of my time just generating ideas. Most of the time I’m designing art works, but I’m quite happy to apply my creativity to anything. This is the first time I’ve ever tried to design a wine bottle, but, by working with specialists, I am actually able to make anything or to produce anything. I can work with a hairdresser and produce a new style of haircut; I worked with a jeweler to make a portrait-projecting wedding ring for my wife; and I’m working with an architect at the moment to redesign the front of a hospital here in Bristol.

I am equally happy to design a wine bottle, or a giant singing sculpture, or a new kind of clock. Anything is possible and it’s quite liberating, really.

IMAGE: Luke Jerram’s “Portrait Projecting Ring.”

I try to work with local specialists wherever possible so that I can support local businesses and craftsmen, and also so that I can keep an eye on what’s going on. I’m a bit of a control freak and it’s just easier to manage people if they are nearby.

Edible Geography: I’d also imagine that some of the design development will happen during fabrication itself, either through serendipitous accidents or through the process of manipulating the materials you’re working with.

Jerram: Absolutely. With all of these things, I end up learning a huge amount about the limitations and the possibilities of a particular craft or a particular skill. For example, I’ve been working with a glass team who helped me create the viral sculptures for about eight years now. They’re working with cold glass — it’s the same skill that you need to make distilling equipment and test tubes and that kind of thing.

I also did a residency at the Museum of Glass in Washington. They use hot glass. You get a punty and a blowpipe and the hot molten glass is like honey when you blow it. Those are two very distinct methods for working with glass, each with quite different constraints and possibilities.

IMAGE: “Adenovirus,” Luke Jerram.

Edible Geography: Which method do you think you might use for this wine bottle project? Or do you have to arrive at a basic form first, before you could answer that?

Jerram: I don’t necessarily need the form, but I have to arrive at a concept, at least. I’ve been generating all sorts of ideas, and now it’s a question of filtering out the good ones from the bad. I used to generate fifteen ideas and I’d hand them to someone and tell them they could choose. Nowadays, I still generate about fifteen ideas, but I’ll only present three or so, each of which I would be happy to make.

Edible Geography: In addition to Wikipedia, have you been looking at any other bottle-related resources for inspiration?

Jerram: I went to the V&A Museum last week and had a look around at their glass collection. I’ve also got friends who are scientists and engineers, so when I put the idea out there, they come back with all sorts of crazy suggestions. It’s a nice thing to talk about in the pub.

One of the things that I am dealing with is that red wine bottles generally have a lot of colour to them, to protect the wine from ultraviolet radiation. If you’ve got a clear bottle full of red wine, sunlight will make the wine go off. But I’m colour-blind, and all of my sculptures are made in transparent glass.

Luckily, Ruggaro’s also open to the idea of making something that’s more like a decanter, which could be clear — and which could be open to the air, to avoid the cork/pressure problems.

IMAGE: Glass gallery at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

Edible Geography: That’s interesting, because the two have quite different purposes. The decanter is about letting the wine breathe, but it’s also about pouring and displaying the wine at a table. Meanwhile, one of the most interesting things about bottles is the idea of distance and distribution — that the wine can now travel between producer and consumer. A bottle — and I suppose, before that, a barrel or an animal skin, even — is the answer to the question of how you get wine from where it is made to where you’re going to drink it.

Jerram: Exactly. The brief really is quite open in that way, which I like. I can choose to be inspired by completely different aspects of the idea of a wine container. I’m really right at the beginning of this journey, just knocking ideas around. Perhaps none of the things that I’m thinking about right now will get made. I’ve got hundreds of ideas, some of which have been on the shelf for five years or more, just waiting for an opportunity to be made.

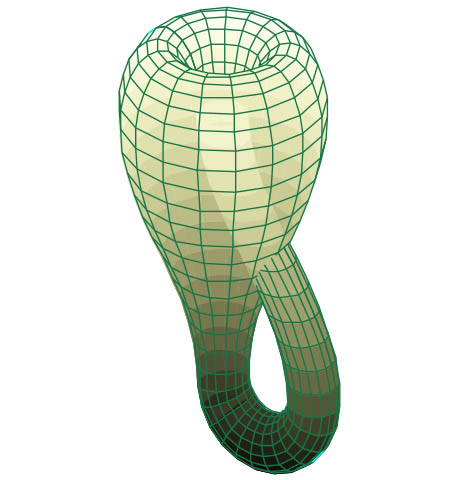

I had one idea to create Dalí-like glass bottles that are melting. You could display them hanging from the ceiling and then you could create melted labels to go with them. That would be a quite nice thing, but is it good enough? Is it interesting enough? I’ve also been thinking about Klein bottles as well, which are these mathematical shapes that only have one surface.

IMAGE: A two-dimensional representation of the Klein bottle, via Wikipedia.

Then there’s the history of wine and what it has meant to us in different eras and cultures and medical regimes. I could make a giant heart-shaped bottle and fill it full of red wine. We could suspend it in a clear jar almost like a pickled formaldehyde sample. That would be quite nice as well. There are all these ideas, and the trick is to choose something has the potential to be far more interesting than you could imagine it to be. In the best projects, it’s not until you actually make the idea that you see that the final result is far more interesting or far better than you thought it could be.

Edible Geography: How long will this idea-generating and winnowing phase take, do you think?

Jerram: Well, I have about twelve projects on the go at the moment, including this one. I don’t know — sometimes you can just spiral around a thing for days or weeks, and then an idea will just fall into your lap at two in the morning, when you were just on the edge of sleep. And then I can also boil up a vat of energy and brainstorm ten ideas within ten minutes. Or I can come up with a few ideas on the train and write them down and then wait for things to fit together.

Edible Geography: Do you drink wine, and, if so, have you found yourself looking at bottles differently as you’re pouring a glass of wine over dinner, or thinking about the role that wine plays in your own life?

Jerram: I can’t really drink red wine. I’ve got a sensitive stomach and red wine does me in. I’m a traditional Englishman, so I drink warm, flat beer.

I have been looking at bottles with a different eye, though. If you go around the V&A’s collection, they’ve got bottles there going back to Roman times. There’s one beautiful glass jug: it’s about twenty-five centimeters tall, and it’s all polished and engraved with a little handle. That’s nice, you think — and then you realize that it is a thousand years old and it has been carved out of a single piece of quartz crystal.

Just imagine starting off with a lump of solid glass and chipping away at it and scooping out the inside to make this incredibly delicate jug. The glass is only about four millimetres thick all around, and the whole thing is carved and etched and it’s absolutely exquisite. Completely bonkers.

IMAGE: Bottle; unknown; 900-1100, from the collection of the V&A.

Edible Geography: That’s amazing. It probably took as long to make as the wine that filled it did.

Jerram: Yes — I would have to imagine that this would take at least six months, and maybe even a year, of continuous work. Then you wonder how many other jugs did they have to make and break before they were able to create one that didn’t get smashed to pieces by accidentally scooping away too much glass from the inside.

Edible Geography: You are drawn to working with glass, clearly, but it does seem like a very nerve-wrackingly fragile material.

Jerram: It is, but I enjoy it. You get quite good at handling it. In a very specific way, it calms you right down.

I lent a couple of my glass viral artworks to the BBC for filming for a program on virology a couple of weeks back. They called, and they said, “Are you sitting down? We are really, really sorry. One of our cameramen knocked it with his elbow and it came off the table and smashed into a million pieces.” They were really apologetic. I was thinking, that’s fine, isn’t it? That’s a sale, as far as I can tell!

IMAGE: A group of wine bottles, from the incredibly thorough Bottle Typing web page maintained by Bill Lindsey for the Society of Historical Archaeology.

Edible Geography: Something about that story makes me think about the afterlife of a wine bottle. After all, the wine is only intended to be in there temporarily, so what happens to the bottle after its contents are gone, other than just becoming a cheesy candle holder for a student flat? Can you design for a post-wine purpose?

Jerram: That’s an interesting question. Actually, one of the ideas that I had was to create a chandelier or a candelabra that was clear and hollow and then you would fill it up with wine. I quite liked the idea of taking a completely different object, like a door or a really ornate frame, and turning it into a bottle by making it hollow. After all, literally anything can be made into a bottle if it’s hollow.

The cork or the seal is the trickiest part. With a cork, you’ve got to put a lot of force into it to get it to work, which then dictates the shape of your bottle to a certain degree. One idea I had was to not to have any cork and, instead, to completely seal the bottle. You wouldn’t be able to drink the wine unless you broke off the top of this long sealed stem. It’s got a bit of a “break in an emergency” feel to it.

IMAGE: Typical wine bottle shapes via Readers’ Digest Australia.

Edible Geography: It reminds me of launching a ship, too. It feels quite ceremonial.

Jerram: I haven’t quite worked that aspect out yet — the closure — although it is quite fundamental. I don’t know. There are so many options. But I’m only ten days into the project!

Check back in the coming months to see how Luke Jerram’s wine bottle design develops….

Update (August 2013): after reviewing some initial concepts, including a gorgeous splash-inspired bottle cast in hot glass, the client couldn’t arrive at a final decision, and the commission came to an end.