Food publishing is a curious business: cookbook sales boom in lockstep with the rise of ready-meals, testifying to a fascination with food that elides the act of actually preparing it. Nonetheless, most follow a proven formula, leavening glossy photos of gorgeously styled food with a sprinkling of concise instructions, titillating sensory details, and hackneyed personal anecdotes.

However, at the outer fringes of the food publishing industry are three projects whose ambitions far exceed the Food Network‘s “dump and stir” model.

First of all, hot off the press comes Food + Sex magazine. It’s destined to be shelved with Cabinet rather than Playboy, by all accounts, and describes its editorial strategy as the “combined effort of artists, writers, farmers and foodmakers exploring how desire shapes the food environment.”

While the preview spreads look to favour vaguely trippy artwork over text, and the thought of “human-incubated yogurt,” as Food + Sex headlines it, makes me feel a little sick, the magazine’s basic premise holds plenty of potential. A couple of essays on bee and worm sex – both essential for food production – seem to promise a Botany of Desire-style insect- and plant’s-eye view of agriculture.

The Penis Mushroom in all its glory. Photo by John W. Allen.

Their article on the frankly incredible psychedelic Penis Mushroom (apparently a reprint of this 2008 piece in Vice) involves Amazonian spores, UV experiments, and an unsolved murder, and is well worth a read. Food + Sex is on tour this month: if you’re in NYC, the Bay Area, or North Carolina’s Triangle, check them out.

Another interesting new food publication is artist Aleksandra Mir‘s How Not To Cook. Her project, a commission from Edinburgh’s Collective Gallery, is a sort of oral history of kitchen catastrophes:

Based on Aleksandra’s personal history of cooking disasters, the project invites 1000 people from all around the world to give their advice of how NOT to cook. With this volume, any reader will be more than well equipped to avoid making the same mistakes in their kitchen.

Cover art for Aleksandra Mir’s The How Not To Cookbook.

You can download a sample pdf here: it is a lovely mixture of the head-noddingly familiar and the head-shakingly idiotic, with a tears-of-laughter-inducing tone of mournful, hard-earned wisdom. Some of my favourites:

A cucumber is a poor substitute when making zucchini bread, no matter how similar they appear.

Do not waste your time going through the whole process of mixing, kneading and baking bread when you do not know what lukewarm is really supposed to mean. When the water is too hot, you will kill your yeast and end up using your hard-as-rock boule as a doorstop.

If you happen upon a large amount of fruit-and-nut-studded cheese, and you do not like it, do not try to make a cheesecake out of it by running it through a food processor with some milk and then baking it. You still will not like it.

If you want to feed your date by cooking tomatoes mixed with eggs take into account that after adding butter and oil do not also add a jar of peanut butter. She will not feel like having sex after eating this.

I could actually just cut-and-paste the whole thing, I enjoyed it so much. Together, these tips transcend their status as funny stories to form an alternative landscape of cooking – a direct and refreshing contrast to the glossily perfect, celebrity-chef food we consume so eagerly in books, magazines, and on TV. As the book’s blurb suggests: “By making our guilty failures public we may even be creating an original and subversive form of art, rather than simply aspiring to obvious and repetitive results.”

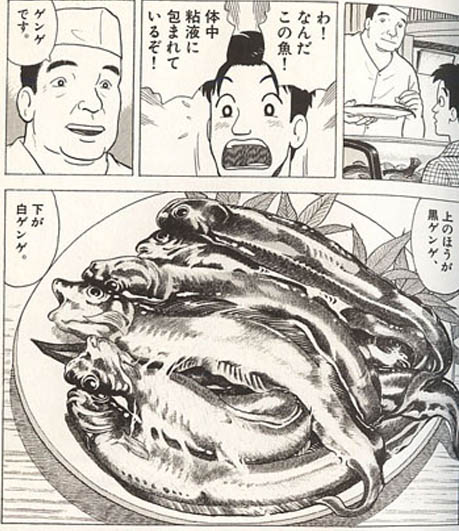

Image from the Japanese version of Oishinbo.

Finally, this article in the June issue of Monocle introduced me to the amazing world of Japanese food manga. “Number one on the charts,” apparently, “is Oishinbo which follows the exploits of a foodie journalist and has sold over 100 million copies since it first appeared in 1983.”

As of January 2009, Oishinbo is also available in English, in a best-of format that collects past issues under thematic headings such as The Joy of Rice and Izakaya – Pub Food.

The cover of the first issue of the English translation of Oishinbo, via Viz Media.

Oishinbo‘s premise is quite intriguing: Yamaoka Shiro, who has a highly refined palate and an estranged father, Kaibara Yuzan, is commissioned by Tozai News to create “The Ultimate Menu,” “a model meal embodying the pinnacle of Japanese cuisine,” as part of the newspaper’s 100th anniversary celebrations.

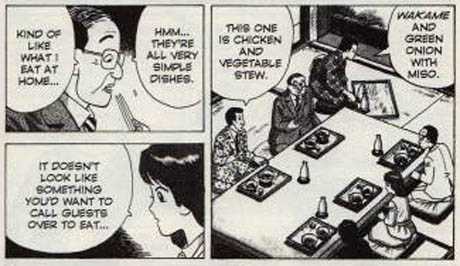

Image from the English translation of Oishinbo, via Viz Media.

Twenty-five years and 126 volumes later, the task is still not complete, but Kaibara has accepted an offer from a rival newspaper to create a competing Ultimate Menu, Yamaoko has married and had children, and readers have been instructed on such vital and complex topics as whether mackerel can ever make truly good sashimi, or how to correctly season sea bream:

The salinity of the water varies a lot in different parts of the inland sea. This is especially the case in the Akashi Strait, which is recessed like a pocket. So I came to the conclusion that the best way to season the fish would be to match the salt level of the seawater that the fish lived in.

The very idea that there could be a perfect expression of Japanese cuisine, and that it would require an epic, lifetime quest to achieve it, says something interesting about the national culture and relationship with food (and is the subject of this subscriber-only article in Gastronomica).

Other top-selling Japanese culinary manga include Cooking Papa, about a salaryman with better kitchen skills than his wife, and the awesome-sounding Professor Genmai’s Bento Box, in which a professor of agriculture lectures his students on farming, fermentation, and constipation.

The latest trend, however, is a wine manga called Kami no Shizuku, or Drops of God, which apparently has a huge influence on the still relatively small Japanese wine-market. According to Shin and Yuko Kibayashi, the manga’s creators, “If we mention a wine, it sells out. We have to be careful when we include wines we like personally.”

Kami no Shizuko cover art, via the Daily Mail.

They are also revolutionising the language of wine description through their hero, Shizuku Kanzaki, who has a completely uneducated palate at first, and likens a 2001 Château Mont-Pérat to the band Queen. After all, as Shin and Yuko say in their interview with Monocle, “Who understands if you say a wine tastes like a ‘wet ash tray’?”

According to the Daily Mail, some South Korean parents even “slip a copy into their children’s suitcase before they leave for university, in the hope it will inspire them to develop sophisticated palates.” The manga has spun off a Japanese Nintendo DS game called Sommelier, and is a huge hit in France, where a younger generation is, according to the publishers, intimidated by fine wine and appreciates learning alongside the clueless hero.

“Of course, grand cultural statements were never the purpose of cookbook writing,” says the anonymous author of “Successful Cookbook Writing” (one of many “Cookbook Writing: Secrets to Success” websites, which are in themselves a fascinating sub-genre). Maybe not – but, as the examples above show, the cultural subtexts that cookbooks, and food writing in general, contain, are an anthropological goldmine.