A confession: the title of this post is lifted directly from an irresistibly enthusiastic history of butter packaging [PDF], prepared by one Milton E. Parker in 1948, for the Packaging Machinery Division of the Lynch Corporation, which I stumbled across while trying to find out how the EU butter molehill is stored.

Parker is an unabashed butter fan, describing it in the first sentence of his treatise as “the everlasting delight of the gourmand, the faithful ally of the culinary arts, the constant symbol of good living,” as well as a sort of “reserve bank,” bringing “farm security and financial stability to the dairy industry.”

IMAGE: Traditional butter pats, via.

Curiously, but in tune with the preoccupations of his historical era, he even notes butter’s superiority over atomic fission in terms of molecular energy:

Granting atomic fission is completely terrible, and […] its sheer power staggers the imagination, we must, nevertheless, recognize that when it comes to molecular energy, butter is still king. For, as Dr. George R. Harrison has pointed out, one pound of butter contains the equivalent of 18,000 B.T.U.’s, while one pound of coal yields 16,000 B.T.U.’s, one pound of TNT lays claim to 2,400 B.T.U.’s, and one pound of uranium (the basic element of the Bomb) can muster only 2,300 B.T.U.’s.

IMAGE: Tinned butter, originally developed to satisfy the demands of gold miners in the Yukon for fresh butter for their flapjacks, via.

The story of butter packaging is, of course, also the story of urbanisation, and the concomitant need to keep food fresh over extended distances and time.

By way of context, Parker collects pre-industrial examples of butter wrapping, ranging from earthenware crocks and pails to “cool cabbage leaves:”

As a matter of fact, it was a common practice in the earlier days of the South Water Street market in Chicago, for farmers to refrigerate their shipments of butter transported in open wagons by covering the same with grass freshly cut while still wet with dew.

Interestingly, Parker’s history also describes butter packaging’s evolution from small, cloth-wrapped rolls or pats, typically made by a local farmers’ wife, to bulk tubs and barrels, produced in a factory creamery and shipped over increasingly large distances — and then back down in size to the individually wrapped sticks we buy today.

IMAGE: Sampling butter barrels at Lurpak’s Danish storage facilities, via.

Parker bemoans the fact that early packaging pioneers rarely kept records as they made butter history, noting that “the question as to when and where the first creamery was started has never been satisfactorily resolved.” Nonetheless, it is clear that the advent of mechanised cream separation and railways combined to make factory-scale butter production, under the “centralized creamery system,” commonplace during the second half of the nineteenth century.

IMAGE: A butter firkin, via.

At this point, Parker explains, the forty, fifty, or even sixty-pound wooden tub “came into general favor” as a butter container, “as both dairymen and creamery men became shippers, their product finding its way to markets such as New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and Chicago where it was sold through commission houses and brokers.”

IMAGE: Soda crackers, via.

Crackers led the way into the next wave of butter packaging — specifically the National Biscuit Company’s introduction of the revolutionary Uneeda soda cracker in 1896. Its “fine, flaky and tasteful” qualities needed protection from breakage, moisture, and rancidity, which was achieved through a “shell-type folding carton of chipboard with an inner wrap of waxed paper.”

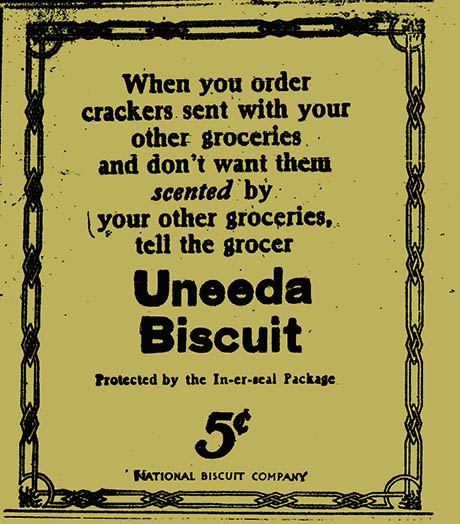

IMAGE: Uneed “In-er-seal” Package advertising, via.

The Uneeda “Inner-Seal” packaging was promoted with a national advertising campaign and met with considerable commercial success.

The butter men were watching, Parker writes, recounting a conversation he had with John S. Parks of the Continental Creamery Company, based in Topeka, Kansas, on the creamery business’s attempts to jump aboard the waxed paper train:

“The National Biscuit Company about that time solved its selling problem by putting on the market crackers in individual pound packages. This particular package was the brainchild of Frank M. Peters… who was… endowed with unusual mechanical ability. Realizing the admirable quality of Peters’ ‘Inner-Seal’ Package for butter, I started negotiations with him for its use.”

Retail — as opposed to bulk — packaging suited the way people were beginning to shop in America’s growing cities: it was time-saving (Parker describes “a strong feeling that developed against returnable packages”), it seemed more sanitary, and, at the dawn of an era when personal knowledge of food producers was beginning to be replaced by trust in brands, it allowed creameries to label their product distinctively. Parker quotes the Elgin Dairy Report on the marketing potential of packaging as early as 1902:

“One of the special advantages of packing butter in this form is the fact that the creamery man can use a copyrighted label or trace mark and thereby hold his trade and create a demand for the quality of goods he is making, if he is making such as to warrant consumers in calling for his brand.”

Parker’s mid-century history thus traces an entire evolution in America’s food system through the otherwise unremarkable medium of butter packaging.

Incidentally, he also points out an early example of an east/west butter divide, with Vermont and northern New York championing spruce for their bulk wooden tubs, while west of the Rockies, ash was the material of choice.

IMAGE: An Elgin packet above a Western stubby, via.

Although both ash and spruce lost out to waxed paper in the end, that divide continues to this day, with Western butter cutting machines having settled on a shorter, fatter shape (known, rather unfortunately, as the “Western stubby”), while the Eastern market prefers longer, thinner sticks, stacked two-by-two, and known as the “Elgin” pack shape (after the Elgin Dairy, which Parker mentions as a strong contender for the title of first butter factory in America).

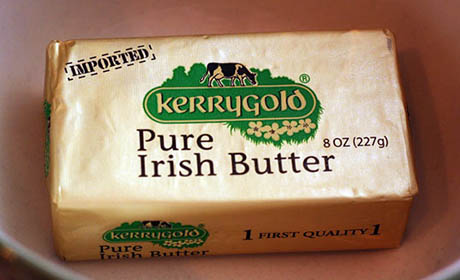

IMAGE: Irish butter, via.

Of course, in Europe, butter is typically sold in much larger rectangles, wrapped in a waxed paper-foil laminate, and it tastes much better due to being made from fermented rather than fresh (“sweet”) cream, but that is another story…