Until recently, the question of whether an apple was truly ripe could only be answered by destroying it.

The human mouth, with its variety of multi-functional sensory detection mechanisms, provides the traditional—and, until recently, the most reliable—guide. But once an apple has been bitten, there is, as Eve reminds us, no going back.

For eaters, this is a simply one of life’s occasional but inevitable disappointments: a mouthful of tasteless mush or eye-watering acid instead of the sweet, crisp crunch of a perfect apple. For fruit growers, it is a serious financial liability. The quality and storage-life of their season’s crop—and thus its value—depend on harvesting the apples at peak ripeness.

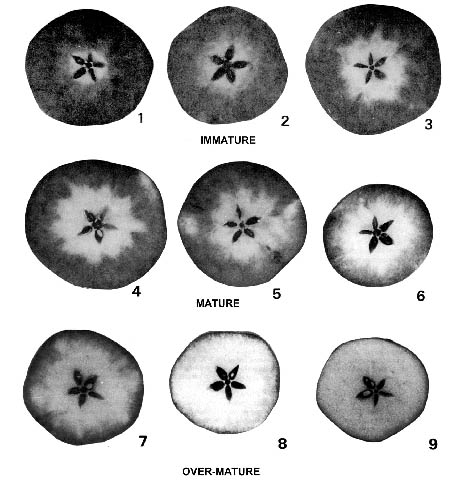

Industry standard ripeness-detection tools add up to little more than a disassembled mouth: the hole-punch-like penetrometer, which, like the human jaw, assesses flesh firmness; the refractometer, a taste bud analogue that measure sugar levels; and the iodine test, which operates in reverse, exposing sugar’s absence. (Iodine reacts with starch, dyeing the apple’s not-yet-sweet tissue purple-black.) All three methods, like their inspiration, the human mouth, require the sacrifice of an apple or several.

IMAGE: Starch iodine test guide for harvesting Red Delicious apples, via.

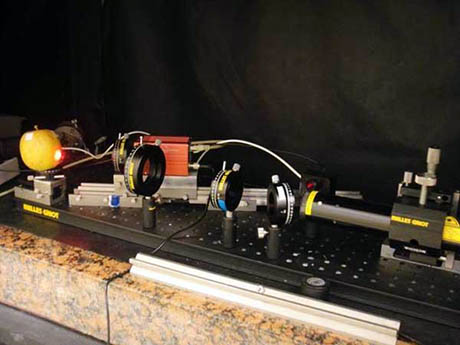

But, as I write in a new post for The New Yorker, a new technique that relies on the granular interference patterns generated by a perceptual mechanism that lies outside human anatomical reach: the laser.

IMAGE: Laser biospeckle measurement array. Photograph by Rana Nassif.

Finally, no apples have to suffer in order to determine a fruit’s peak ripeness: that elusive moment of maximum crunch and sweetness, before the inexorable softening sets in. The mouth, released from its analytical responsibilities, can dedicate itself entirely to a retirement of guaranteed pleasure.

For more on the laser-filled orchards of the future, read my story in full at The New Yorker.