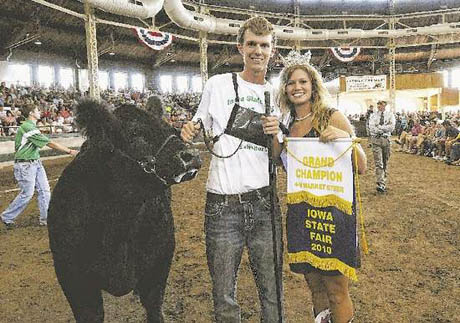

IMAGE: Tyler Faber with “Doc,” receiving his grand champion 4-H market steer award from Iowa State Fair queen Lacy Stevensen. Photo by Steve Pope for the Iowa State Fair.

As today’s New York Times points out, it’s state fair season in America: a time for deep-fried salad, loosely bolted-together Ferris wheels, and — almost anachronistically in this age of Cargill and ConAgra — farm animals. But amidst the nostalgia-laden petting zoo and cattle auctions, the cutting-edge of industrial food technology has reared its controversial head.

In Iowa — a state whose agricultural enterprise is already front page news thanks to Mr. DeCoster’s egg-producing practices — the 2010 State Fair’s 4-H grand champion prize-winner was a 1320 lb steer called “Doc.” He was shown by Tyler Faber, who also won the same contest in 2008 with “Wade,” clocking in at 1310 lbs.

Apart from the 10 lbs difference between the two steers, however, there was very little else to tell them apart: “Doc” was cloned from “Wade” by Faber’s father, who runs Trans Ova Genetics of Sioux Center.

IMAGE: “Wade,” 2008 grand champion 4-H market steer, with Tyler Farber and family. Photo courtesy of the Iowa State Fair.

IMAGE: Tyler Farber is hugged by his sister Sara after one of his victories — the Des Moines Register caption is appropriately vague as to whether the steer in the photo is “Wade” or “Doc.” Photo by Mary Chind.

As reported in the Des Moines Register, “‘Doc’ is the first cloned animal to win a 4-H livestock blue ribbon at the fair,” but “the cloned animal was not illegal in the judging competition.” According to Mike Anderson, Iowa State University Extension specialist and 4-H livestock judging director, “We didn’t know at the time that Doc was a clone, but it’s not against the rules.”

Anderson added that “the issue might be discussed when 4-H officials meet with the State Fair Board in October,” but “rules against cloned steers in judging competitions would be difficult to enforce.”

The source of this difficulty is fascinating: because (rather obviously, if you think about it) there is no scientific test that can determine whether an animal is a clone or not, Faber’s disgruntled competitors would have no way to prove their own entries were not themselves clones. For all the judging panel can possibly know, they might all be clones.

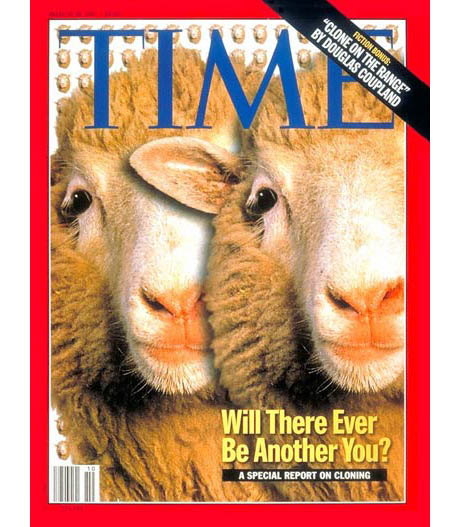

IMAGE: “Dolly,” the first mammal to be cloned from an adult cell, on the cover of Time magazine. She died young in 2003.

Outside the world of state fair competitions, this ambiguity has had some interesting repercussions. In the U.S., where the sale of meat from clones has been legal since 2008 (albeit subject to a voluntary moratorium at the request of the U.S.D.A., to avoid scaring foreign trade partners), meat cannot be labeled with its clone/non-clone origins.

The F.D.A., which regulates such matters, holds that the “only grounds for labeling food are if there are any safety concerns or if there is a material difference in the composition of food.” As the Iowa State Fair blue-ribbon competition shows, there is no test that can determine whether an animal is a clone or not, and the F.D.A. has already ruled that meat from cloned animals is perfectly safe*, which means that, theoretically, a consumer who does not buy organic could have been unknowingly eating prime rib from the “same” cow every night for the past several years.

IMAGE: Farmer Steven Innes, who sold the offspring of a cloned bull for meat, causing uproar in the U.K., where such transactions are illegal. Photo by David Moir for Reuters.

This is not a completely far-fetched scenario. In a 2008 online discussion at the Washington Post, staff writer Rick Weiss notes that:

There is good evidence […] that lots of those offspring [of clones] have entered the food stream in recent years. One cattleman I spoke to said thousands have probably done so.

Meanwhile, just a couple of weeks ago, when Canadian officials asked U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack whether meat from clones might have entered the North American food chain, he replied:

I can’t say today that I can answer your question in an affirmative or negative way. I don’t know.

As a side note inspired by Iowa’s current egg woes: given the absence of labeling, let alone a clone DNA database, just imagine trying to recall all the meat from the offspring of a particular clone…

IMAGE: Image via Bovance, who also provide detailed instructions for the emergency procedures required to genetically preserve post-mortem cattle.

But food safety concerns and quasi-existential questions on the impossibility of distinguishing clones aside, the labeling question throws up another intriguing wrinkle. Weiss explains that the economic value in cloning lies in ramping up the production of high-end sperm: the investment in creating a clone of a particularly large and virile Hereford or an especially lusciously fat-marbled Kobe steer — or even an endangered heritage breed bull — pays off in an infinite reservoir of guaranteed high-quality reproductive matter that can be sold on to cattle farmers for artificial insemination.

Given this business model, Weiss notes, it makes sense that once the small matter of public unease is overcome, meat packers might actually want to label meat with its clone origins. The problem is that there is no accepted terminology to describe the offspring of clones, or “Meat from an animal conceived by artificial insemination in which sperm from a clone was squirted into a cow’s uterus,” as Weiss rather un-appetisingly puts it. What should these half-clone/half-non-clone animals be called? And what about their offspring in turn? Or their clones? Or, indeed, their offspring’s clones? Suggestions in the comments, please.

* At one point in the Washington Post online discussion, Rick Weiss explains the slightly terrifying working assumptions that lie behind the FDA’s safety ruling:

The FDA could not decide whether this [epigenetic] difference poses a health risk to consumers, mostly because they know very little about the NORMAL patterns of gene activity in conventional animals, and even less about the relevance of those patterns to food safety and nutrition. In the end, they decided that, lacking evidence that it poses a problem (and given that the ones [clones] with really disrupted gene regulation LOOK sick, and so would not pass muster at the slaughterhouse) they would just ignore it.

[NOTE: Thanks to always informative Agricultural Biodiversity Weblog for the link to the Iowa State Fair clone story.]