IMAGE: A fish captured during the Malaspina Expedition. Credit: CSIC / JOAN COSTA.

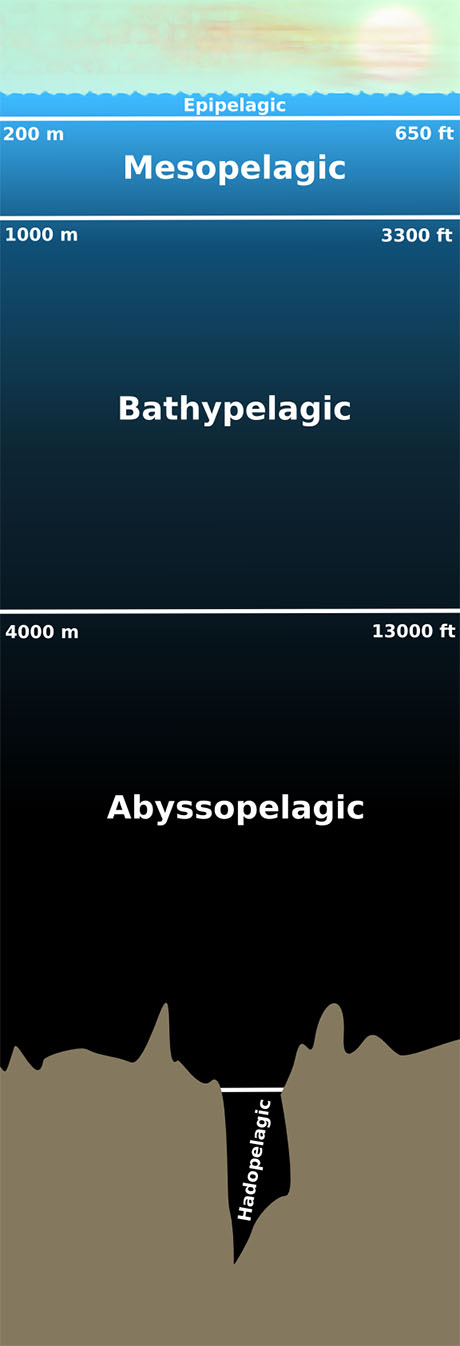

If you descend below two hundred metres in the world’s oceans, you enter the mesopelagic, or twilight, zone. The temperature plummets, pressure increases, light levels drop off quickly to almost nothing at all, and the water is filled with a continuous shower of “marine snow” — flakes of dead or dying plankton, algae, fecal matter, sand, and dust.

The fish that live in this zone are, to put it charitably, very strange-looking. There are blobfish, snailfish, slimeheads (known at your local fishmonger as orange roughy), the red-luminescence producing stoplight loosejaw, and the brownsnout spookfish, which is apparently the only vertebrate known to employ a mirror, as opposed to a lens, to focus.

What’s more, there are enormous numbers of these mesopelagic fish. In fact, there are so many that they create a sort of false sea floor: apparently, when sonar first began to be widely used during World War II, frustrated operators kept detecting what looked like solid ground at about 300 metres, even when they knew the ocean bed was a thousand or more metres deeper than that that. It proved to be an acoustic illusion created by the swim bladders of millions and millions of mesopelagic fish.

IMAGE: Scale diagram of marine zones by Finlay McWalter.

Last month, a team of researchers published the results of a new mesopelagic census. Scientists had previously estimated that this zone contained 1,000 million tons of fish; the new census, led by Spanish National Research Council researcher Carlos Duarte, discovered that there are actually between 10 and 30 times more than that.

In other words, these odd-looking, little-known, and for the most part completely unharvested fish make up an incredible 95 percent of all marine biomass. All of a sudden, there are a lot more fish in the sea.

All these bristlemouths and lanternfishes had managed to hide from hungry humans because of their enhanced vision and pressure-sensitivity. According to Duarte, “They are able to detect nets from at least five metres and avoid them.” Large trawl nets are the primary technology humans use to count fish, and these net-avoiding fish were thus invisible and inaccessible to us: “marine dark matter,” as Jason Kottke puts it.

Duarte’s seven-month global circumnavigation used sonar and echo sounding instead, extrapolating mesopelagic fish numbers based on their acoustic backscatter. Not only did the expedition’s findings revise fish population numbers up by an order of magnitude, they also showed that the oceanic gyres — rotating spirals of plastic waste previously assumed to be marine dead zones — are mesopelagic hotspots, home to what Duarte calls “the largest fish stock in the ocean”:

This very large stock of fish that we have just discovered, that holds 95 per cent of all the fish biomass in the world, is untouched by fishers. They can’t harvest them with nets. In the 21st Century we have still a pristine stock of fish which happens to be 95 per cent of all the fish in oceans.

Found via Kottke.org.