The story below is cross-posted from Venue , where you can also read about lunar analogues in Arizona, prison visiting room portrait backdrops, cave organs, and more. Venue — a pop-up interview studio and multimedia rig traveling around North America through September 30, 2013 — is a project of the Nevada Museum of Art’s Center for Art + Environment, Future Plural, and Studio-X NYC, with funding provided by the Western States Arts Federation (WESTAF), Nevada Arts Council, and the National Endowment for the Arts.

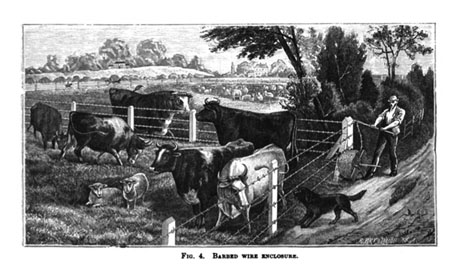

When European farmers arrived in North America, they claimed it with fences. Fences were the physical manifestation of a belief in private ownership and the proper use of land — enclosed, utilised, defended — that continues to shape the American way of life, its economic aspirations, and even its form of government.

Today, fences are the framework through the national landscape is seen, understood, and managed, forming a vast, distributed, and often unquestioned network of wire that somehow defines the “land of the free” while also restricting movement within it.

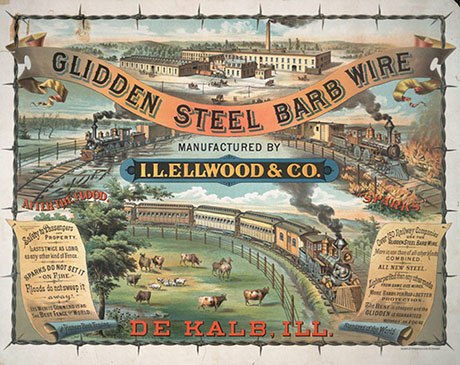

In the 1870s, the U.S. faced a fence crisis. As settlers ventured away from the coast and into the vast grasslands of the Great Plains, limited supplies of cheap wood meant that split-rail fencing cost more than the land it enclosed. The timely invention of barbed wire in 1874 allowed homesteaders to settle the prairie, transforming its grassland ecology as dramatically as the industrial quantities of corn and cattle being produced and harvested within its newly enclosed pastures redefined the American diet.

In Las Cruces, New Mexico, Venue met with Dean M. Anderson, a USDA scientist whose research into virtual fencing promises equally radical transformation — this time by removing the mile upon mile of barbed wire stretched across the landscape. As seems to be the case in fencing, a relatively straightforward technological innovation — GPS-equipped free-range cows that can be nudged back within virtual bounds by ear-mounted stimulus-delivery devices — has implications that could profoundly reshape our relationships with domesticated animals, each other, and the landscape.

In fact, after our hour-long conversation, it became clear to Venue that Anderson, a quietly-spoken federal research scientist who admits to taping a paper list of telephone numbers on the back of his decidedly unsmart phone, keeps exciting if unlikely company with the vanguard of the New Aesthetic, writer and artist James Bridle’s term for an emerging way of perceiving (and, in this case, apportioning) digital information under the influence of the various media technologies—satellite imagery, RFID tags, algorithmic glitches, and so on—through which we now filter the world.

The Google Maps rainbow plane, an iconic image of the New Aesthetic for the way in which it accidentally captures the hyperspectral oddness of new representational technologies and image-compression algorithms on a product intended for human eyes.

After all, Anderson’s directional virtual fencing is nothing less than augmented reality for cattle, a bovine New Aesthetic: the creation of a new layer of perceptual information that can redirect the movement of livestock across remote landscapes in real-time response to lines humans can no longer see. If gathering cows on horseback gave rise to the cowboy narratives of the West, we might ask in this context, what new mythologies might Anderson’s satellite-enabled, autonomous gather give rise to?

Our discussion ranged from robotic rats and sheep laterality to the advantages of GPS imprecision and the possibility of high-tech herds bred to suit the topography of particular property. The edited transcript appears below, reposted from the Venue site.

Nicola Twilley: I thought I’d start with a really basic question, which is why you would want to make a virtual fence rather than a physical one. After all, isn’t the role of fencing to make an intangible, human-determined boundary into a tangible one, with real, physical effects?

Pasture fence; photograph via Cheyenne Fence.

Dean M. Anderson: Let me put it this way, in really practical terms: When it comes to managing animals, every conventional fence that I have ever built has been in the wrong place the next year.

That said, I always kid people when I give a talk. I say, “Don’t go out and sell your U.S. Steel stock—because we are still going to need conventional fencing along airport runways, interstates, railroad right-of-ways, and so on.” The reason why is because, when you talk about virtual fencing, you’re talking about modifying animal behaviour.

Then I always ask this question of the audience: “Is there anybody who will raise their hand, who is one hundred percent predictable, one hundred percent of the time?”

The thing about animal behaviour is that it’s not one hundred percent predictable, one hundred percent of the time. We don’t know all of the integrated factors that go into making you turn left, when you leave the building, rather than right and so on. Once you realize that virtual fencing is capitalising on modifying animal behaviour, then you also realize that if there are any boundaries that, for safety or health reasons, absolutely cannot be breached, then virtual fencing is not the methodology of choice.

I always start with that disclaimer. Now, to get back to your question about why you’d want to make a virtual fence: On a worldwide basis, animal distribution remains a challenge, whether it’s elephants in Africa or Hereford cows in Las Cruces, New Mexico.

Photograph via Singing Bull Ranch, Colorado.

You will have seen this, although you may not have recognised exactly what you were looking at. For example, if you fly into Albuquerque or El Paso airports, you will come in quite low over rangeland. If you see a drinking water location, you will see that the area around that watering point looks as brown and devoid of vegetation as the top of this table, whereas, out at the far distance from the drinking water, there may be plants that have never seen a set of teeth, a jaw, or any utilisation at all.

So you have the problem of non-uniform utilisation of the landscape, with some places that are over utilised and other places that are underutilised. The over utilised locations with exposed soil are then vulnerable to erosion from wind and water, which then lead to all sorts of other challenges for those of us who want to be ecologically correct in our thinking and management actions.

Even as a college student, animal distribution was something that I was taught was challenging and that we didn’t have an answer to. In fact, I recently wrote a review article that showed that, just in the last few years, we have used more than sixty-eight different strategies to try to affect distribution. These include putting a fence in, developing drinking water in a new location, putting supplemental feed in different locations, changing the times you put out feed, putting in artificial shade, so that animals would move to that location—there are a host of things that we have tried. And they all work under certain conditions. Some of them work even better when they’re used synergistically. There are a lot of combinations—whatever n factorial is for sixty-eight.

Cattle clustered under a neatly labeled portable shade structure; photograph via the University of Kentucky College of Agriculture.

But one thing that all of them basically don’t allow is management in real time. This is a challenge. Think of this landscape — the Chihuahuan desert, which, by the way, is the largest desert in North America. If you’ve been here during our monsoon, when we (sometimes) receive our mean annual nine-inches plus of precipitation, you’ll see that where Nicola is sitting, she can be soaking wet, while Geoff and I, just a few feet away, stay bone dry. Precipitation patterns in this environment can be like a knife cut.

Students learning rangeland analysis at the Chihuahuan Desert Rangeland Research Center; photograph by J. Victor Espinoza for NMSU Agricultural Communications.

You can see that, with conventional fencing, you might have your cows way over on the western perimeter of your land, while the rainfall takes place along the other edge. In two weeks, where that rain has fallen, we are going to have a flush of annuals coming up, which would provide high-quality nutrition. But, if you have the animals clear over three pastures away, then you’ve got to monitor the rainfall-related growth, and you’ve got to get labour to help round those animals up and move them over to this new location.

You can see how, many times as a manager, you might actually know what to do to optimise your utilisation, but economics and time prevent it from happening. Which means your cows are all in the wrong place. It’s a lose-lose, rather than a win-win.

One of Dean Anderson’s colleagues, Derek Bailey, herds cattle the old-fashioned way on NMSU’s Chihuahuan Desert Rangeland Research Center. One aspect of Bailey’s research is testing whether targeted grazing, made possible through Anderson’s GPS collar technology, could reduce the incidence of catastrophic western wildfires. Photograph courtesy NMSU.

These annual plants will reach their peak of nutritional quality and decline without being utilised for feed. I’m not saying that seed production is not important, but, if part of this landscape’s call is to support animals, then you are not optimising what you have available.

My concept of virtual fencing was to have that perimeter fence around your property be conventional, whether it’s barbed wire, stone, wood, or whatever. But, internally, you don’t have fences. You basically program “electronic” polygons, if you will, based upon the current year’s pattern of rainfall, pattern of poisonous weed growth, pattern of endangered species growth, and whatever other variables will affect your current year’s management decisions. Then you can use the virtual polygon to either include or exclude animals from areas on the landscape that you want to manage with scalpel-like precision.

To go back to my first example, you could be driving your property in your air-conditioned truck and you notice a spot that received rain in the recent past and that has a flush of highly nutritious plants that would otherwise be lost. Well, you can get on your laptop, right then and there, and program the polygon that contains your cows to move spatially and temporally over the landscape to this “better location.” Instead of having to build a fence or take the time and manpower to gather your cows, you would simply move the virtual fence.

whitespace

This video clip shows two cows (the red and green dots) in a virtual paddock that was programmed to move across the landscape at 1.1 m/hr, using Dean Anderson’s directional virtual fencing technology.

It’s like those join-the-dots coloring books — you end up with a bunch of coordinates that you connect to build a fence. And you can move the polygon that the animals are in over in that far corner of the pasture. You simply migrate it over, amoeba-like, to fit in this new area.

You basically have real-time management, which is something that is not currently possible in livestock grazing, even with all of the technologies that we have. If you take that concept of being able to manage in real time and you tie it with those sixty-eight other things that have been found useful, you can start to see the benefit that is potentially possible.

Twilley: The other thing that I thought was curious, which I picked up on from your publications, is this idea that perhaps you might not be out on the land in your air-conditioned pickup, and instead you might actually be doing this through remote sensing. Is that possible?

Dean Anderson’s NMSU colleague, remote sensing scientist Andrea Laliberte, accompanied by ARS technicians Amy Slaughter and Connie Maxwell, prepare to launch an unmanned aerial vehicle from a catapult at the Jornada Experimental Range. Photograph USDA/ARS.

Anderson: Definitely. Currently we have a very active program here on the Jornada Experimental Range in landscape ecology using unmanned aerial vehicle reconnaissance. I see this research as fitting hand-in-glove with virtual fencing. However — and this is very important — all of these whiz-bang technologies are potentially great, but in the hands of somebody who is basically lazy, which is all human beings, or even in the hands of somebody who just does not understand the plant-animal interface, they could create huge problems.

If you don’t have people out on the landscape who know the difference between overstocking and under-stocking, then I will want to change my last name in the latter years of my life, because I don’t want to be associated with the train wreck — I mean a major train wreck — that could happen through using this technology. If you can be sitting in your office in Washington D.C. and you program cows to move on your ranch in Montana, and you don’t have anybody out on the ground in Montana monitoring what is taking place …. [shakes head] You could literally destroy rangeland.

We know that electronics are not infallible. We also know that satellite imagery needs to be backed up by somebody on the ground who can say, “Wow, we’ve got a problem here, because what the electronic data are saying does not match what I’m seeing.”

This is the thing that scares me the most about this methodology. If people decouple the best computer that we have at this point, which is our brain, with sufficient experience, from knowing how to optimise this wonderful tool, then we will have a potential for disaster that will be horrid.

NMSU and USDA ARS scientists prepare to launch their vegetation surveying UAV from a catapult. Photograph USDA/ARS.

Twilley: One of the things I was imagining as I looked at your work was that, as we become an increasingly urban society, maybe farmers could still manage rural land remotely, from their new homes in the city.

Anderson: They can, but only if they also have someone on the ground who has the knowledge and experience to ground-truth the data — to look at it and say, “The data saying that this number of cows should be in this polygon for this many days are accurate” — or not.

You need that flexibility, and you always need to ground-truth. The only way you can get optimum results, in my opinion, is to have someone who is trained in the basics of range science and animal science, to know when the numbers are good and when the numbers are lousy. Electronics simply provide numbers.

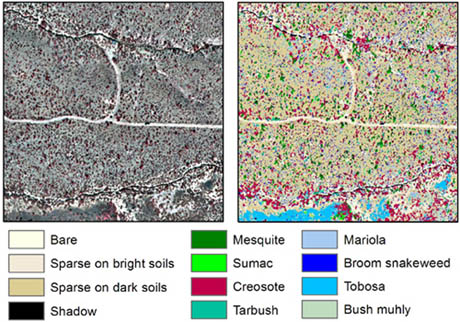

Multispectral rangeland vegetation imagery produced by Andrea Laliberte’s UAV surveys. Image from “Multispectral Remote Sensing from Unmanned Aircraft,” by Andrea S. Laliberte, Mark A. Goforth, Catriana M. Steele, and Albert Rango, 2011.

Now, you’re right, we are getting smarter at developing technology that can interpret those numbers. I work with colleagues in virtual fencing research who are basically trying to model what an animal does, so that they can actually predict where the animal is going to move before the animal actually moves. In my opinion if they ever figure that out, it’s going to be way past my lifetime.

Still, if you look at range science, it’s an art as well as science. I think it’s great that we have these technologies and I think we should use them. But we shouldn’t put our brain in a box on a table and say, “OK. We no longer need that.” Human judgment and expertise on the ground is still essential to making a methodology like this be a positive, rather than a negative, for landscape ecology.

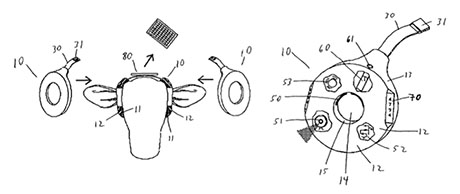

Drawings from Anderson’s patent #7753007 for an “Ear-a-round equipment platform for animals.”

Manaugh: I’m curious about the bovine interface. How do you interface with the cow in order to stimulate the behaviour that you want?

Anderson: I think that basically my whole career has been focused on trying to adopt innate animal behaviours to accomplish management goals in the most efficient and effective ways possible.

Here’s what I mean by that. I can guarantee that, if a sound that is unknown and unpleasant to the three of us happens over on that side of the room, we’re not going to go toward it. We’re going to get through that door on the other side as quickly as possible.

What I’m doing is taking something that’s innate across the animal world. If you stimulate an animal with something unknown, then, at least initially, it’s going to move away from it. If the event is also accompanied by an unpleasant ending experience and the sequence of events leading up to the unpleasant event are repeatable and predictable, after a few sequential experiences of these events, animals will try and avoid the ending event — if they’re given the opportunity. This is the principle that has allowed the USDA to receive a patent on this methodology.

The thing, first of all, about our technique is that it’s not a one-size-fits-all. In other words, there are animals that you could basically look at cross-eyed and they’ll move, and then there are animals like me, where you’ve got to get a 2×6 and hit them up across the head to get their attention before anything happens.

When these kinds of systems have been built for dog training or dog containment in the past, they simply had a shock, or sometimes a sound first and then a shock. The stimulus wasn’t graded according to proximity or the animal’s personality.

Dean Anderson draws the route of a wandering cow approaching a virtual fence in order to show Venue how his DVF™ system works.

[stands up and draws on whiteboard] Let’s say that this is the polygon that we want the animal to stay in. If we are going to build a conventional fence, we would put a barbed wire fence or some enclosure around that polygon. In our system, we build a virtual belt, which in the diagrams is shaded from blue to red. The blue is a very innocuous sound, almost like a whisper. Moving closer to the edge of the polygon, into the red zone, I ramp that whisper up to the sound of a 747 at full throttle takeoff. I can have the sound all the way from very benign up to pretty irritating. At the top end, it’s as if a fire alarm went off in here — we’re going to get out, because it sounds terrible.

whitespace

This video clip captures the first-time response of a cow instrumented with Dean Anderson’s directional virtual fencing electronics when encountering a static virtual fence, established using GPS technology.

I’ve based the sounds and stimuli that I’ve used on what we know about cow hearing. Cows and humans are similar, but not identical. These cues were developed to fit the animal that we are trying to manage.

Now, if we go back to me as the example, I’m very stubborn. I need a little higher level of irritation to change my behaviour. We chose to use electric stimulation.

I used myself as the test subject to develop the scale we’re using on this. My electronics guys were too smart. They wouldn’t touch the electrodes. I’m just a dumb biologist, so…

Diagram showing how directional virtual fencing operates. The black-and-white dashed line (8) shows where a conventional fence would be placed. A magnetometer in the device worn on the cow’s head determines the animal’s angle of approach. A GPS system in the device detects when the animal wanders into the 200m-wide virtual boundary band. Algorithms then combine that data to determine which side of the animal’s to cue, and at what intensity. From Dean M. Anderson’s 2007 paper, “Virtual Fencing: Past, Present, and Future” (PDF).

If I’m the animal and I’m getting closer and closer to the edge of the polygon, then the electrodes that are in the device will send an electrical stimulation. In terms of what those stimulations felt like to me, the first level is about like hitting the crazy bone in your elbow. The next one is like scooting across this floor in your socks and touching a doorknob — that kind of static shock. The final one is like taking and stopping your gas-powered lawnmower by grabbing the spark plug barehanded.

What we did was cannibalise a Hot-Shot that some people buy and use to move animals down chutes. I touched the Hot-Shot output and I could still feel it in my fingertips the next morning, so we cut it right down for our version

As the cow moves toward the virtual fence perimeter, it goes from a very benign to a fairly irritating set of sensory cues, and if they’re all on at their highest intensity , it’s very irritating. It’s the 747s combined with the spark plug. Now, back from your eighth-grade geometry, you know that you have an acute angle and you have an obtuse angle. As the cow approaches a virtual fence boundary, we send the cues on the acute side, to direct her away from the boundary as quickly and with as little amount of irritation as possible. If we tried to move the cow by cuing the obtuse side, she would have had to move deeper into the irritation gradient before being able to exit it.

We don’t want to overstress the animal. So we end up, either in distance or time or both, having a point at which, if this animal decides it really wants what’s over here, it’s not going to be irritated to the point of going nuts. We have built-in, failsafe ways that, if the animal doesn’t respond appropriately, we are not going to do anything that would cause negative animal welfare issues.

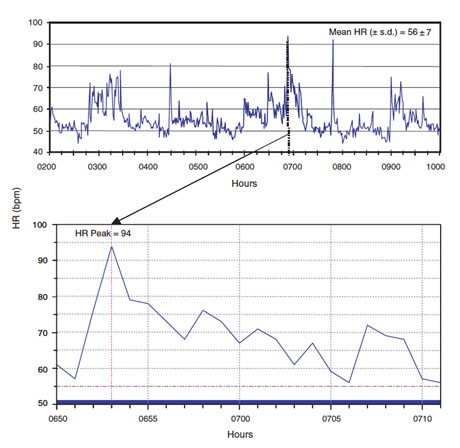

Heart rate profile (beats per minute) of an 8-year-old free-ranging cross-bred beef cow before, during, and after an audio plus electric stimulation cue from a directional virtual fencing device. The cue was delivered at 0653 h. The second spike was not due to DVF cues; the cow was observed standing near drinking water during this time. From Dean M. Anderson’s 2007 paper, “Virtual Fencing: Past, Present, and Future” (PDF).

The key is, if you can do the job with a tack hammer, don’t get a sledgehammer. This is part of animal welfare, which is absolutely the overarching umbrella under which directional virtual fencing was developed. There’s no need to stimulate an animal beyond what it needs. I can tell you that when I put heart rate monitors on cows wearing my DVF™ devices. I actually found more of a spike in their heart rates when a flock of birds flew over than when I applied the sound.

Now, there are going to be some animals that you either get your rifle and then put the product in your freezer, or you go put the animal back into a four-strand barbed wire fenced pasture. Not every animal on the face of the earth today would be controllable with virtual fencing. You could gradually increase the number of animals that do adapt well to being managed using virtual fencing in your herd through culling.

But the vast majority of animals will react to these irritations, at some level. They can choose at which point they react, all the way from the whisper to the lawnmower.

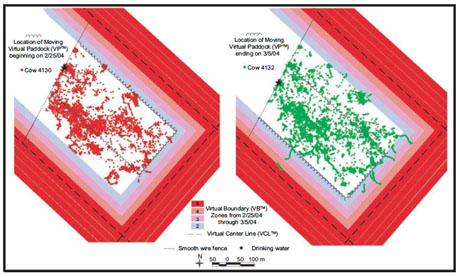

Diagram showing two cows responding differently to the virtual boundary: Cow 4132 (in green) penetrates the boundary zone more deeply, tolerating a greater degree of irritation before turning around. From Dean M. Anderson’s 2007 paper, “Virtual Fencing: Past, Present, and Future” (PDF).

Here is the other thing: We all learn. Whatever we do to animals, we are teaching them something. It’s our choice as to what we want them to learn.

Of course, I don’t have data from a huge population that I can talk about. But, of the animals with whom I have worked — and the literature would support what I’m going to say — cows are, in fact smarter than human beings in a number of ways. If I give you the story of the first virtual fencing device that I built, I think you’ll see why I say that.

What our team did initially was cannibalise a kids’ remote control car to send a signal to the device worn by the animal. I had a Hereford/Angus cross cow, and she was a smart old girl. I started to cue her. I was close to her and she responded to the cues exactly the way I wanted her to. But she figured out, in less than five tries, that, if she kept twenty-five feet between me and her, I could press a button, and nothing would happen. I tried to follow her all over the field. She just kept that distance ahead of me for the rest of the trial — always more than twenty-five feet!

So that’s the reason why we are using GPS satellites to define the perimeter of the polygon. You can’t get away from that line.

A cow being fitted with an early prototype of Dean Anderson’s Ear-A-Round DVF device. Photograph via USDA Jornada Experimental Range, AP.

What sets DVF™ apart from other virtual fencing approaches is that it’s not a one-size-fits-all. The cues are ramped, and the irritating cues are bilaterally applied, so we can make it directional, to steer the animals — no pun intended — over the landscape.

What’s interesting is that if you have the capacity to build a polygon, you can encompass a soil type, a vegetation situation, a poisonous plant, or whatever, much better than you can if you have to build a conventional fence. In building conventional fences, you have to have stretch posts every time you change the fence’s direction. That increases both materials and labor costs in construction, which is why you see many more rectangular paddocks than multi-sided polygons. Right now, you can assume that, on flat country, about fifty percent of the cost in a conventional fence is labour, and the other fifty percent is material.

Stretching barbed wire around a corner, shown in this engraving from A Treatise Upon Wire: Its Manufacture and Uses, Embracing Comprehensive Descriptions of the Constructions and Applications of Wire Ropes, J. Bucknall Smith, 1891.

Twilley: Which raises another question: Is virtual fencing cost-effective?

Anderson: It depends. I’ll give you an example to show what I mean. The US Forest Service over in Globe, Arizona, is interested in possibly using virtual fencing. Some of the mining companies over there have leases that say that before they extract the ore, and even after, the surface may be leased to people with livestock.

That country over there is pretty much like a bunch of Ws put together. In March 2012, for two-and-a-half miles of four-strand barbed wire, using T posts, they were given a quote of $63,000.

That’s why they called me. [laughs]

Now, if that was next to a road, even if it cost $163,000 for those two-and-a half miles of fence, it would be essential, in my opinion, that they not think about virtual fencing — not in this day and time.

In twenty years from now — somewhere in this century, at least — after the ethical and moral issues have been worked out, instead of stimulating animals with external audio sound or electrical stimulation, I think we will actually be stimulating internally at the neuronal level. At that point, virtual fencing may approach one hundred percent effective control.

The DARPA “Robo Rat,” whose movements could be directly controlled by three electrodes inserted into its brain; photograph via.

It’s been done with rodents. The idea was that these animals could be equipped with a camera or other sensors and sent into earthquake areas or fires or where there were environmental issues that humans really shouldn’t be exposed to. Of course, even if it can be done scientifically, there are still issues in terms of animal welfare. What if there is a radiation leak? Do you send rodents into it? You can see the moral and ethical issues that need to be worked out.

Twilley: If that ever becomes a real-world application, will you sell your shares in U.S. Steel?

Anderson: [laughs] I have a feeling that we never will have a landscape devoid of visible boundaries. If nothing else, I want a barbed wire fence between Ted Turner’s ranch and our experimental ranch up the road here. With a visible boundary, there’s no question — this side is mine and that side is yours.

Fencing photograph via InformedFarmers.com. Incidentally, Ted Turner’s Vermejo ranch in New Mexico and southern Colorado is said to be the largest privately-owned, contiguous tract of land in the United States.

Twilley: Aha — so it’s the human animals that will still need a physical fence.

Anderson: I think so. Otherwise you’re looking at the landscape and there’s absolutely nothing out there — whether it be to define ownership or use or even health or safety hazards.

Manaugh: Do you think this kind of virtual fencing would have any impact on real estate practices? For example, I could imagine multiple ranchers marbling their usage of a larger, shared plot of land with this ability to track and contain their herds so precisely. Could virtual fencing thus change the way land is controlled, owned, or leased amongst different groups of people?

Anderson: If you were to go down here to the Boot Heel area of New Mexico you could find exactly that: individual ranchers are pooling areas to form a grass bank for their common use.

Anything that I can do in my profession to encourage flexibility, I figure I’m doing the correct thing. That’s where this all came from. It never made sense to me that we use static tools to manage dynamic resources. You learn from day one in all of your ecology classes and animal science classes that you are dealing with multiple dynamic systems that you are trying to optimise in relationship to each other. It was a mental disconnect for me, as an undergraduate as well as a graduate student, to understand how you could effectively manage dynamic resources with a static fence.

Now, there are some interesting additional things you learn with this system. For example, believe it or not, animals have laterality. You probably didn’t see the article that I published last year on sheep laterality. [laughter]

USDA ARS scientists testing cattle laterality in a T-Maze. Photograph by Scott Bauer for the USDA ARS.

Twilley and Manaugh: No.

Anderson: Our white-faced sheep, which have Rambouillet and Polypay genetics, were basically right-handed. You’ll want to take a look at the data, of course, but, basically, animals are no different than you and I. There are animals that have a preference to turn right and others that have a preference to turn left.

Now, I didn’t do this study to waste government money. Think about it in terms of what I have told you about applying the cues bilaterally. If I know that my tendency is right-handed, then in order to get me to go left, I may need a higher level of stimulation on my right side than I would if you were trying to get me to go right by applying a stimulus on my left side, because it’s against my natural instincts.

With the computer technology we have today, everything we do can be stored in memory, so you can learn about each animal, and modify your stimulus accordingly. There is no reason at all that we cannot design the algorithms and gather data that, over time, will make the whole process optimised for each animal, as well as for the herd and the landscape.

Cow equipped with a collar-mounted GPS device; photography by Dave Ganskoop for the USDA ARS.

Twilley: Going back to something you said earlier about animal memory — and this may be too speculative a question to answer — I’m curious as to how dynamic virtual fencing affects how cows perceive the landscape.

Anderson: The question would be whether, if the virtual fence is on or near a particular rock, or a telephone pole, or a stream, and they have had electrical stimulation there before, do they associate that rock or whatever with a limit boundary? In other words, do they correlate visual landmarks with the virtual fence? Based on some non-published data I have collected, the answer is yes.

In fact, to give some context, there have been studies published showing that for a number of days following removal of an electric fence, cattle would still not cross the line where it had been located.

So this could indeed be an issue with virtual fencing, but — and my research on this topic is still very preliminary — I have not seen a problem yet, and I don’t think I will. Part of the reason is that cows want to eat, so if the polygon that contains the animals is programmed to move toward good forage, the cows will follow. It’s almost like a moving feed bunk, if you will. I’m sure that, in time — I would almost bet money on this — that if you were using the virtual fence to move animals toward better forage, you could almost eliminate the virtual fence line behind the animals, especially if the drinking water was kept near the “moving feed bunk.”

The other thing is that the consumer-level GPS receivers I have used in my DVF™ devices do not have the capability to have the fixes corrected using DGPS, which means that the fix may actually vary from the “true” boundary by as much as the length of a three-quarter ton pick-up. That’s to my benefit, because there is never an exact line where that animal is sure to be cued and hence the animal cannot match a particular stone or other environmental object with the stimulation event even if the virtual boundary is held static. It’s always going to be just in the general area.

A cow fitted with an early prototype of Anderson’s Ear-A-Round DVF system at the Jornada Experimental Range; photograph via AP/Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Iuliu Vasilescu.

Manaugh: So imprecision is actually helpful to you.

Anderson: Yes, I believe so — although I don’t have enough data that I would want to stand on a podium and swear to that. But I think the variability in that GPS signal could be an advantage for virtual paddocks that spatially and temporally move over the landscape.

Twilley: We’ve talked about optimising utilisation and remote management, but are we missing some of the other ways that virtual fencing might transform the way we manage livestock or the land?

Anderson: Ideas that we know are good, but are simply too labour-intensive right now, will become reasonable. The big thing that has been in vogue for some time — and it still is, in certain places — is rotational stocking. The idea is that you take your land and divide it into many small paddocks and move animals through these paddocks, leaving the animals in any one paddock for only a few hours or days. It’s a great idea under certain situations, but think of the labour of building and maintaining all those fences, not to mention moving the animals in and out of different paddocks all the time.

A fence in need of repair; photograph via.

With the virtual paddock you can just program the polygon to move spatially and temporally over the landscape. Even the shape of the virtual paddock can be dynamic in time and space as well. It can be slowed down where there’s abundant forage, and sped up where forage is limited so you have a completely dynamic, flexible system in which to manage free-ranging animals.

Here’s another thing. Like anybody who gathers free-ranging animals, I have a song I use. My song is pretty benign and can be sung among mixed audiences. [sings] “Come on sweetheart, let’s go. Come on. Come on. Come on, girls. Let’s go.”

whitespace

In this video clip, a cow-calf pair are moved using only voice cues (Dean Anderson’s gathering song) delivered from directional virtual fencing (DVF™) electronics carried by the cows on an ear-a-round (EAR™) system.

That’s the way I talk to them, if I want them to move. One day when I was out manually gathering my cows on an ATV I put a voice-activated recorder in my pocket and recorded my song. We later transferred the sounds of my manual gathering into the DVF™ device. Then when we wanted to gather the animals we wirelessly activated the DVF™ electronics and my “song” — “Come on, girls, let’s go” — began to play. Instead of a negative irritation, this was a positive cuing — and it worked.

The cows moved to the corral based on the cue, without me actually being present to manually gather them — it was an autonomous gather.

I think this type of thing also points to a paradigm shift in how we manage livestock. Sure, I can get my animals up in the middle of night to move them, but why do that? Why not try to manage on cow time, rather than our own egotistical needs — “At eight o’clock, I want these cows in so I can brand them,” or whatever. Why not mesh management routines with their innate behaviours instead? For example, my song could maybe be matched to correspond to a general time of day when the animals might start drifting in to drink water, anyway.

Twilley: I see — it’s a feedback loop where you’re cuing behaviour with the GPS collars, but you’re also gathering data. You can see where they are already heading and change your management accordingly.

Anderson: Absolutely. You are matching needs and possibilities.

Manaugh: To make this work, does every animal have to be instrumented?

Anderson: This is a very valid question, but my answer varies. All the research needed to answer this question is not in, and the answers depend on the specific situation being addressed. I have a lot of people right now who are calling me and asking for a commercial device that they can put on their animals because they are losing them to theft. With the price of livestock where it is currently, cattle-rustling is not a thing of the nineteenth century. It is going on as we speak.

If that’s your challenge, then you’re going to need some kind of electronic gadgetry on every animal for absolute bookkeeping. For me, the challenge is how do you manage a large, extensive landscape in ways that we can’t do now, and I don’t think we necessarily need to instrument every animal for virtual fencing to be effective.

Instead, if you’ve got a hundred cows, you need to ask: which of those cows should you put instruments on? As a producer, you probably have a pretty good idea which animals should be instrumented and why: you would look for the leaders in the group.

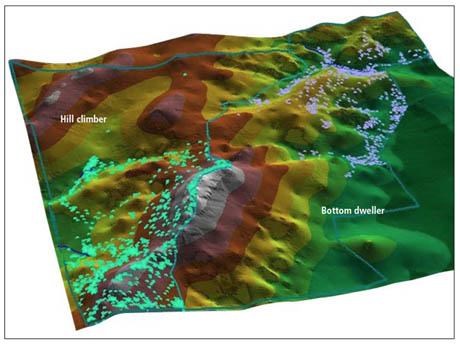

Position of two cows grazing similar pastures in Montana, recorded every ten minutes over a two-week period. The difference in their grazing patterns reveal one cow to be a hill climber and one to be a bottom dweller. Image form a USDA Rangeland Management publication (PDF) co-authored by Derek Bailey, NMSU.

What’s interesting is that there are cows that prefer foraging up on top of hills. There are others that prefer being down in a riparian area. A colleague of mine at New Mexico State University, calls them bottom dwelling and hill climbing cows and this spatial foraging characteristic apparently has heritability. So it’s possible that you could select animals that fit your specific landscape. If, as I mentioned earlier, the ease with which an animal can be controlled by sensory cues also has heritability, it seems logical to assume that you could create hightech designer animals tailored to your piece of land.

Now, when you start adding all of these things together, using these electronic gadgetries and really leveraging innate behaviours, it points to a revolution in animal management — a revolution with really powerful potential to help us become much better stewards of the landscape.

This photograph shows a worm fence, an American invention. It was the most widely built fence type in the US through the 1870s, until Americans ran out of readily accessible forests, triggering a “fence crisis,” in which the costs of fencing exceeded the value of the land it enclosed. The “crisis” was averted by the invention of mass-produced woven wire in the late 1800s. Photograph from the USDA History Collection, Special Collections, National Agricultural Library.

Twilley: None of this is commercially available yet, though, right?

Anderson: That’s true — you cannot go out today and buy a commercial DVF™ system, or for that matter any kind of virtual fence unit designed specifically for livestock, to the best of my knowledge. But there is a company that is interested in our patent and they are trying to get something off the ground. I’m trying to feed this company any information that I can, though I am not legally allowed to participate in the development of their product as a federal employee.

Manaugh: What are some of the obstacles to commercial availability?

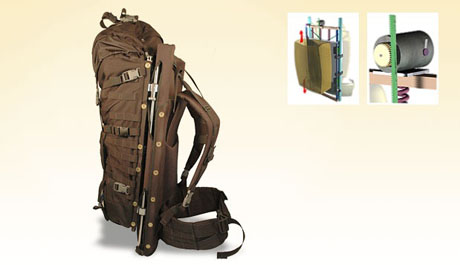

Anderson: The largest immediate challenge I see is answering the question of how you power electronics on free-ranging animals for extended periods of time. We have tried solar and it has potential. I think one of the most exciting things, though, is kinetic energy. I understand that there are companies working on a technology to be used in cellphones that will charge the cell phone simply by the action of lifting it out of your purse or pocket, and the Army has got several things going on now with backpacks for soldiers that recharge electronic communication equipment as a result of a soldier’s walking movement.

Lawrence Rome’s kinetic backpack.

I don’t think the economics warrant animal agriculture developing any of these power technologies independently, but I think we can capitalise on that being developed in other, more lucrative industries and then simply adapt it for our needs. When I developed the concept of DVF™ I designed it to be a plug-and-pray device. As soon as somebody developed a better component, I would throw my thing out and plug theirs in—and pray that it would improve performance. Sometimes it did and sometimes it didn’t!

Manaugh: Have you looked into microbial batteries?

Anderson: That’s an interesting suggestion that I have not looked into. However, I have though a lot about capturing kinetic energy. If you watch a cow, their ears are always moving, and so are their tails. If we can capture any of that movement….

The other thing we need is demand from the market. In 2007, I was invited to the UK to discuss virtual fencing — the folks in London were more interested in virtual fencing than anybody else I have ever talked to in the world.

The reason was really interesting. England has a historic tradition of common land, which is basically open “green space” that surrounds the city and was originally used for grazing by people who had one or two sheep or cows. Nowadays, it’s mostly used by dog walkers, pony riders — for recreation, basically. The problem is that they need livestock back on these landscapes so certain herbaceous vegetation does not threaten some of the woody species. However, none of the present-day users want conventional fencing because of the gates that would have to be opened and shut to contain the animals. So they were interested in virtual fencing as a way to get the ecology back into line using domestic herbivores, in a landscape that needs to be shared with pony riders and dog walkers who don’t want to shut gates and might not do it reliably, anyway.

But it’s an interesting question. I’ve had some sleepless nights, up at two in the morning wondering, “Why is it not being embraced?” I think that a lot of it comes strictly down to economics.

I don’t know, at this point, what a setup would cost. But, in my opinion, there are ways we could implement this immediately and have it be very viable. You wouldn’t have every animal instrumented. You can have single-hop technology, so information uploads and downloads at certain points the animals come to with reliable periodicity — the drinking water or the mineral supplement, say. That’s not real-time, of course — but it’s near real-time. And it would be a quantum leap compared to how we currently manage livestock.

Barbed wire, patented by Illinois farmer Joseph Glidden in 1874, opened up the American prairie for large-scale farming. Photograph by Tiago Fioreze, Wikipedia.

Twilley: What do the farmers themselves think of this system?

Anderson: What I’ve heard from some ranchers is something along the lines of: “I’ve already got fences and they work fine. Why do I need this unproven new technology?”

On the other hand, dairy farmers who have automatic milking parlours, which allow animals to come in on their own volition to get milked, think virtual fencing would be very appropriate for their type of operation, for reasons of convenience rather than economics.

Robotic milking parlour; photograph via its manufacturer, DeLaval.

Now, let me tell you what I think might actually work. I think that environmentalists could actually be very beneficial in pushing this forward. Take a situation where you have an endangered bird species that uses the bank of a stream for nesting or reproduction. Under current conditions, the rancher can’t realistically afford to fence out a long corridor along a stream just for that two-week period. That’s a place where virtual fencing is a tool that would allow us to do the best ecological management in the most cost-effective way.

But the larger point is that we cannot afford to manage twenty-first century agriculture using grandpa’s tools, economically, sociologically, and biologically.

I.L. Elwood & Co. Glidden Steel Barb Wire, non-dated Advertising Posters, Advertising Ephemera Collection, Baker Library Historical Collections, via.

Some people have said, “Well, I think you are just ahead of your time with this stuff.” I’m not sure that’s true. In any case, in my personal opinion, if I’m not doing the research that looks twenty years out into future before it’s adopted, then I’m doing the wrong kind of research. In 2005, Gallagher, one of the world’s leading builders of electric fences, invited me to talk about virtual fencing. During that conversation, they told me that they believe that, by the middle of this century, virtual fencing will be the fencing of choice.

But here’s the thing: none of us have gone to the food counter and found it empty. When you have got a full stomach, the things that maybe should be looked at for that twenty-year gap are often not on the radar screen. As long as the barbed wire fences haven’t rusted out completely, the labour costs can be tolerated, and the environmental legislation hasn’t become mandatory, then why spend money? That’s human nature. You only do what you have to do and not much more.

The point is that it’s going to take a number of sociological and economic factors, in my opinion, for this methodology of animal control to be implemented by the market. But speaking technologically, we could go out with an acceptable product in eighteen months, I believe. It wouldn’t have multi-hop technology. It would equal the quality of the first automobile rather than being comparable to a Rolls Royce in terms of “extras” — that would have to await a later date in this century.

And here’s another idea: I think that there ought to be a tax on every virtual fencing device that is sold or every lease agreement that’s signed in the developed world. That tax would go to help developing countries manage their free-ranging livestock using this methodology because that’s where we need to be better stewards of the landscape and where we as a world would all benefit from transforming some of today’s manual labour into cognitive labour.

Herding cattle the old-fashioned way on the Jornada Experimental Range; photograph by Peggy Greb for USDA ARS.

Maybe with this technology, a third-world farmer could put a better thatched roof on his house or send his kids to school, because he doesn’t need their manual laboir down on the farm. It’s fun for a while to be out on a horse watching the cows; what made the West and Hollywood famous were the cowboys singing to their cows. I love that; that’s why I’m in this profession. Still, I’m not a sociologist, but it seems as though you could take some of that labour that is currently used managing livestock in developing countries and all of the time it requires and you could transfer it into things that would enhance human well-being and education.

It’s in our own interest, too. If non-optimal livestock management is creating ecological sacrifice areas, where soil is lost when the rains come or the wind blows, that particulate matter doesn’t stop at national boundaries.

I always say that virtual fencing is going to be something that causes a paradigm shift in the way we think, rather than just being a new tool to keep doing things in the same old way. That’s the real opportunity.