IMAGE: Bottles of holy water (available at the Sacramentals Foundation of Omaha, Nebraska) and a radish.

In a paper published in the journal Psychological Reports in 1979, Sandra Lenington measured the mean growth of 12 radish seeds watered with holy water against that of 12 radish seeds watered with tap water. It was not, Lenington concluded, “significantly different.”

Lenington, a life coach specialising in “Radiant Recovery” whose career has included spells as a research engineer at NASA Ames and as a Curves franchise owner, initiated her experiment in an attempt to reproduce the findings of Canon William V. Rauscher, who had previously reported “that canna plants given holy water left over from use in from use in religious services grew more than three times higher than canna plants which were not given holy water.”

Having secured a glass container full of holy water from a local church that used the same municipal source as the Santa Clara University tap water, as well as two identical watering cans, Lenington watered her seedlings every other day for three weeks and then measured them. After reporting her null finding, she goes on to speculate that Rauscher’s previous results might have been due to his belief in the power of holy water to affect plant growth. In her own case, she writes, “the author had no expectations of the outcome.”

Another critical difference was that Rauscher had dipped his hands in his holy water, whereas the water received by Lenington’s radishes had only been blessed. “Is the ‘laying on of hands’ necessary or helpful for a transfer of energy to take place?” Lenington wonders. “Future work to check differences in growth rates of plants given prayer while being touched versus plants given prayer alone might prove interesting.”

Finally, a more mundane consideration: the holy water was only changed weekly, meaning that “it was necessarily older and had been sitting a little longer than the tap water.”

Despite the irresistible temptation to giggle at this experiment—it, like many of my favourite examples of scientific research, has been featured in the Annals of Improbable Research—it also serves as an interesting reminder of a recurring debate in plant science: the thorny question of plant intelligence.

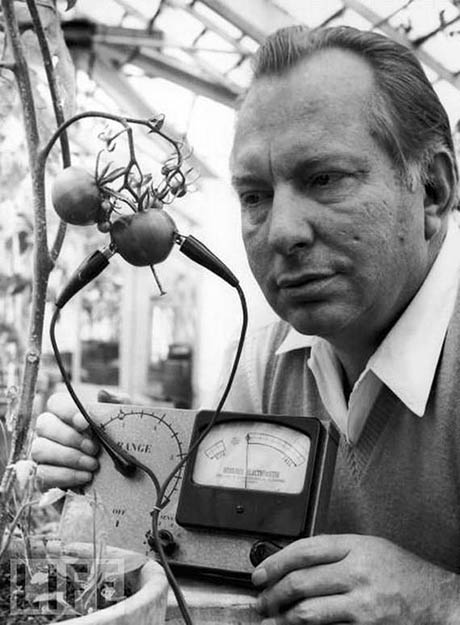

IMAGE: L. Ron Hubbard, better known as the founder of Scientology, attempting to measure whether tomatoes experience pain, in 1968. Photo: Getty Images.

As Michael Pollan pointed out in his recent essay for the New Yorker, a New Age-inspired belief in plant sentience was not uncommon in the 1970s. Former C.I.A. analyst Clive Backster had spent the late 1960s measuring plant-human thought transference by attaching a polygraph machine to tomatoes and bananas, and The Secret Life of Plants was a nonfiction best-seller when it was published in 1973. Seen in this context, Sandra Lenington’s holy water-irrigated radishes tell us less about vegetables, and rather more about humans and the limitations of the conceptual structures from within which we examine the world.

What is fascinating is that, although many of these original experiments have since been discredited, botanists have recently, if tentatively, returned to the idea of plant intelligence. And, just as Lenington did in 1979, they have done so using the dominant metaphors of our time. The scientists quoted in Pollan’s (fascinating) article draw heavily on twenty-first century buzz words to explain plant-based phenomena: “modular,” “resilience,” “emergent,” and “networks” are all used repeatedly.

Just as the new technology of the railway provided an analogy that helped Einstein to develop, as well as explain, his theory of relativity, and just as the invention of the telephone both reflected and structured how scientists understood the human nervous system, so, too, it seems with our ability to understand how a plant experiences and functions in the world: it is both expanded and limited by the available metaphors. From telekinesis to distributed intelligence, we think like our technology when we try to think like a plant.

Previously in vegetable metaphors on Edible Geography: “The Carrot Hack”. Sandra Lenington’s study discovered via @kyledropp.