At the New York State Department of Conservation’s fyke net in Richmond Creek on Staten Island, nightly glass eel catch totals have tapered off. Further north, in the Bronx River, the annual migration of tiny, translucent baby eels will continue for another couple of weeks. And, in Maine, one of only two states to allow a commercial catch, a few hundred licensed elver fishermen are currently sleeping in their cars, some with guns, in order to defend their nets against poachers, while banks are running low on bills as dealers pay up to $2,000 in cash per pound for their harvest.

IMAGE: Elver migration, photograph by Andrew Fahlund. Glass eels metamorphose into elvers, becoming slightly rounder and darker, once they reach the coast.

This annual eel run is “probably the most miraculous example of migratory evolution on the planet,” according to Chris Bowser, the science education specialist charged with recruiting and running the D.E.C.’s American Eel Research Project. All the way along the East Coast, from South Carolina to Maine, writhing ribbons of these two- to three-inch-long transparent worm-like fish are finding their way into estuaries and up to the freshwater rivers they will call home for up to twenty years. They have made their way to the coast from spawning grounds in the Sargasso Sea (the world’s only sea without a land boundary), just east of Bermuda, in a migratory pattern that is still a scientific mystery.

IMAGE: Glass eels, via.

Eels migrate in precisely the opposite direction to other homing fish species. In other words, while a salmon or shad spends most of its adult life in the sea, returning to the river it was born in to spawn, the American eel is born at sea, floats to the shore on prevailing currents, and chooses its river home seemingly at random, before heading back to its original spawning ground to reproduce and die.

To add to their mystery, most aspects of the eel lifecycle are still unknown to science. As James Prosek, author of Eels: An Exploration, From New Zealand to the Sargasso, of the World’s Most Mysterious Fish, and the director of a new documentary, The Mystery of Eels (which you can watch in full online), explains, no one knows what prompts them to move into freshwater, no one knows how they distribute themselves throughout their range, no one knows what determines their adult gender (although density is correlated to masculinity), and no one has ever witnessed the holy grail of eel research: an adult eel spawning.

Katsumi Tsukamoto, a Japanese scientist featured in Prosek’s film, speculates that the adult aggregate into a large ball and spawn simultaneously, in a sort of eel orgy, but this is pure conjecture — after a lifetime’s research, he has come tantalisingly close, netting fresh eel eggs (which only last 36 hours), but has now had to retire. Chris Bowser added a similar, historical anecdote of eel frustration: apparently, one of Sigmund Freud’s earliest research projects, long before writing The Interpretation of Dreams, was an inconclusive attempt to find the European eel’s gonads.

IMAGE: Pier 15, designed by SHoP architects, and photographed (in low-light with an iPhone, sorry) by me.

Prosek and Bowser (present in, he was keen to stress, an entirely unofficial capacity) had come together to share their enthusiasm for the enigmatic eel at a Sunday-evening meeting of artist Natalie Jeremijenko’s Cross-Species Adventure Club. We met in the future maritime education center building on Pier 15 in Manhattan, a city-funded effort to re-connect New Yorkers to the waters that surround their urban archipelago. Jeremijenko’s own agenda seems, on the surface, similar, but is actually much more radical: the Cross-Species Adventure Club is actually a series of design interaction experiments, intended to transform human relationships with the urban ecosystem into a form of cultivation rather than extraction or damage, or even just straightforward preservation.

“As an environmental mantra, ‘leave no trace,'” Jeremijenko told the assembled Adventurers, “is a bit pathetic. It assumes that we can extract ourselves from our ecosystem — and that we are only capable of negative impact. Can’t we interact with our environment in a way that has a positive effect?”

IMAGE: Cross-Species Adventure Club lures; photograph via Natalie Jeremijenko.

Earlier Cross-Species Adventure Club projects demonstrate ways to put this philosophy into action. For example, Jeremijenko has designed a lure made of gin & tonic-flavoured gellan mixed with chelating agents that remove heavy metals from bio-availability, with the idea that, rather than throwing Doritos and bread at fish in ponds, snacking humans could satisfy their urge to feed fish while also engaging in cumulative acts of environment remediation — and, perhaps most importantly, re-thinking their own place in the urban ecosystem.

This particular Cross-Species Adventure, however, was much less tightly resolved. It began with Chris Bowser describing his fantastic citizen science project, which has been recording baby American eel numbers during the Hudson spring migration since 2008. Volunteers count and weigh each night’s catch at sites along the length of the river, and then release the eels, in some cases further upstream, past any dams or diversions that might have blocked their journey. Although eels are not yet listed as endangered, access to eighty-four percent of the freshwater tributaries on the Atlantic seaboard — the adult eels’ potential homes — has been restricted or cut off altogether.

IMAGE: Images from a report by Chris Bowser’s Hudson River Eel Project (pdf), showing a fyke net, students holding up a bag of elvers and glass eels, and students re-setting the net.

A screening of Prosek’s film then filled in some context on eel science, as well as human/eel relationships around the world (in addition to American eels, there are a number of other species of freshwater eel, or Anguillidae), from eel-worshiping Pacific Islanders to Tokyo eel slaughterhouses capable of cleaning, skewering, and grilling more than 4,000 eels per day.

Indeed, it is the Japanese hunger for eels (they consume more than 130,000 tons each year), combined with the increasing scarcity of their native eel and an E.U. ban on elver export, that has pushed Maine glass eel prices so high. Dealers sell the baby eels to Japanese fish farms, who have worked out how to raise them in captivity to precisely two times the size of a standard bento box, but not how to reproduce them economically, making them dependent on wild-caught seed stock.

IMAGE: Inside a Tokyo eel slaughterhouse. Photograph by David Doubilet for National Geographic.

Educated and fascinated, we were each then given an eel cocktail — or rather, a glass full of glass eels, with a salt water mixer — and asked to consider the question of what a productive human interaction with an eel could be.

IMAGE: With glass eels working out at about $1 each at today’s prices, this was not a cheap cocktail, despite being alcohol free. Photograph by Nicola Twilley.

Jeremijenko had bought half a pound of baby eels from a Maine dealer, diverting them from their sushi fate, and then driven them down to New York City with the intention of offering us the opportunity to release them into the East River.

Bowser was not aware of this plan, and quickly pointed out that not only is it actually illegal to stock fish without a permit, it is also a bad idea: we have no idea what factors made the eels chose Maine, rather than New York, in the first place, and we also don’t know whether they might be carrying any diseases (eel conservationists are increasingly concerned about a swim-bladder parasite that is present in aquaculture operations and has now appeared in the wild).

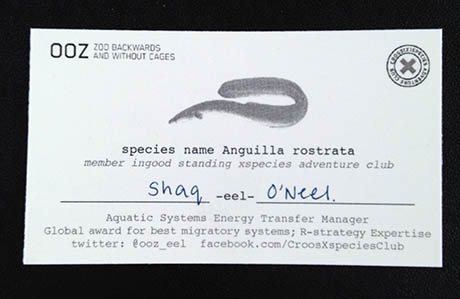

IMAGE: As part of our eel bonding experience, we were asked to name an eel. This was my attempt. Photograph by Nicola Twilley.

“If you ask me, we should put them in a frying pan with some olive oil and garlic for just a second or two,” Bowser said, describing the taste as “like al dente pasta.” No one seemed to be in a hurry to take him up on this advice, and, instead, for the next hour, we held the eels in our hands (they move constantly, in a way that is ticklish rather than slimy), watched their hearts pump and gills flap inside their translucent bodies, marvelled as they propelled themselves up the sides of the glass, and discussed the various roles of eels and humans in the aquatic food chain.

We learned that baby eels are an important food source for all kinds of other fish, that eels are inveterate cannibals, and that they eat anything that’s too large to inhale using a drilling technique that involves sinking their teeth into the meat and then rotating up to fifteen times per second, until a smaller chunk breaks off. As we became increasingly attached to our tiny eels with their black button eyes, Bowser noted that he wouldn’t recommend keeping an eel as a pet, because “they’re famous escape artists. One day you’ll come home to an empty aquarium and a dead stinky eel hidden somewhere in your apartment.”

IMAGE: A glass eel on a Cross-Species Adventure Club attendee’s hand. Photograph by Nicola Twilley.

IMAGE: Natalie Jeremijenko’s glass eel aquarium. Photograph by Nicola Twilley.

Gradually, we “released” our seven or eight eels into the larger aquarium, and went home, newly enchanted by eels and newly frustrated by our inability to imagine a productive interaction with them. Perhaps that was, in itself, the most productive interaction possible.

One Comment

Thank you – I didn’t know about these eels or the future maritime ed center at Pier 15.

I hope the Cross-Species Adventure Club will offer something for the younger set – they are quite experientially oriented and flora & fauna fascinated.