One-minute idling ordinances. Restricted streets and inherited parking spots. Minimum pavement width. Health-department inspections. A $500 “refreshment vehicle assistant” licensing fee…

IMAGE: New York City’s vending regulations book, photo by Candy Chang for Urban Omnibus.

At both Foodprint NYC and Foodprint Toronto, the subject of street food trucks has come up in the “Zoning Diet” panel: a perfect case-study of the way economic and regulatory forces play out at the street level to shape an urban, mobile food delivery system.

Indeed, based on the evidence in Toronto and New York, street food vending provides something of a cautionary tale, as cities try to use the design tools at their disposal — from parking tickets to permit caps — to optimise the economic, health, and street-life building potential of mobile food vending, but instead end-up handicapping vendors with, for example, 1,000 lb trucks (which can’t be stored on the street overnight, but which “the city had designed specifically so they couldn’t be towed”).

IMAGE: “Toronto a la cart vendor Issa Ashtarieh sells falafel and kebab at the corner of University Ave. and College St.” Photo by Lucas Oleniuk for the Toronto Star.

In Toronto, clumsy regulation seems to be strangling food cart initiatives at birth, while in New York, restrictions promote resistance. On the one hand, vendors are currently using petitions, hot pink fake parking tickets, and passionate courtroom depositions to challenge proposed new legislation that would revoke a vendor’s license if they receive three or more parking or idling citations within twelve months.

IMAGE: Food trucks run by disabled veterans in front of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Photo by Ashley Gilbertson for The New York Times. According to reporter Simon Akam, “A 19th-century state law allows disabled veterans to sell in some areas that are off limits to others,” however, some carts simply “rent-a-vet” to sit in front of the cart in order to take advantage of their location dispensation.

And on the other hand, New York’s nearly three-decade-old cap of 3000 food-cart licenses and the tempting economics of street vending combine to produce the food cart underground — a black-market in food-cart permits that, according to Sean Basinski, Foodprint NYC panelist and Director of the Street Vendor Project, “the health department knows exists, but they look the other way.”

IMAGE: Street Vendor Project Director Sean Basinski speaking at Foodprint NYC. Photo by Ho Kyung Lee, Columbia GSAPP.

The health department’s gaze may be averted, but the street food underground does receive some scrutiny: while going through a stack of old New Yorkers (a favourite pre-move packing procrastination technique), I came across Busted by Larissa MacFarquhar, a fantastic article from the February 1, 2010, issue, on New York City’s Department of Investigation, whose job is to track down “fraud and corruption among city employees and people who deal with them.”

In a lengthy subsection, MacFarquhar describes a sting set up by Chis Staackmann, the D.O.I.’s inspector general for the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, and Byron, one of his “main undercover men,” to gather evidence of a food-cart inspection scam:

Food-vending carts were required to undergo inspection at the city’s inspection station, in Maspeth, but many of the carts were too dilapidated to pass. There were operations in Queens that would supply a vender with a clean, new cart, put it through the inspection process, and then transfer the inspection decal from that cart to the vender’s old, broken one.

Incredibly, the D.O.I. knew for sure that this was happening because “they had begun tagging carts with invisible ink,” and were seeing the same carts come through the inspection station “over and over again.”

IMAGE: Cop writing up a ticket for a falafel truck in DUMBO. Photo via Brownstoner.

What they didn’t know is how the vendors were able to transfer the inspection decal despite the Department of Health’s precautions, which included extremely strong glue and a hologram of the world “VOID” that was supposed to appear if the sticker was removed.

Did they apply a heat torch from behind the metal panel? Did they coat the side of the cart with some kind of lubricant so that the decal never stuck on properly in the first place? Did they treat the metal with graphite? […] Nobody could figure out how they did it.

The story unfolds with the enjoyably absurdist drama that only a bureaucratic procedural can offer — Chris and Byron are staked out in a Boston Market parking lot, and abandon their call signs after forgetting which one of them is “H1” and which is “H2” — the D.O.I. fails to gather any visual evidence against the suspected decal swappers at Steve’s Sheet Metal. And as a result, although Steve and his colleague Fernando plead guilty to misdemeanours, the mechanics of decal removal remain a mystery.

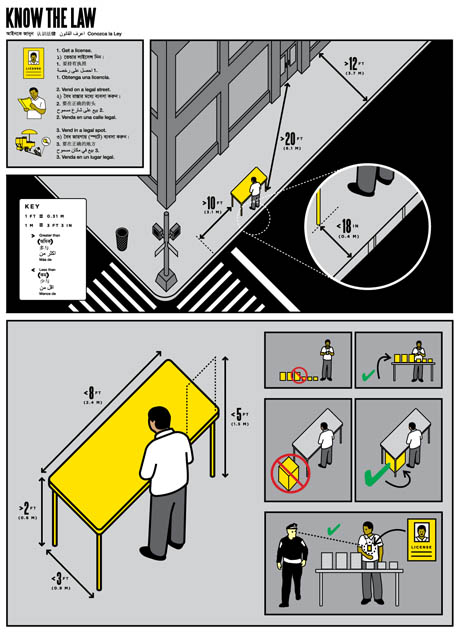

IMAGE: A spread from designer Candy Chang’s awesome Vendor Power! booklet, created as an educational/advocacy tool in collaboration with the Center for Urban Pedagogy and the Street Vendor Project. Read more about it on BLDGBLOG.

As Larissa MacFarquhar tells it, this story’s anticlimactic ending is apt, given the frustrating nature of much of the D.O.I.’s work: “an endless game of Whack-a-Mole,” applying band-aids rather than “fixing the city.” But, as we have seen at Foodprint NYC and Foodprint Toronto, fixing the city is not so easily achieved, and opinions differ on how it should be done.

For example, the D.O.I.’s Chris Staackmann tells Larissa MacFarquhar that he is “going to recommend that food venders should have to take their own carts to inspection and get their I.D.-card photographs retaken every year. That would make it harder for someone to sell his permit illegally and then leave the country.” Meanwhile, Sean Basinski and the Street Vendor Project think that the city “should revoke permits from people who are no longer using them, and reissue them to current vendors who desperately need them,” as well as “simply issue more permits.”

And of course, there is always the the D.O.I.’s core business: the problem of human susceptibility to the economic temptations of black-market food vending, dodgy plumbing, welfare skimming, and construction short-cuts:

They couldn’t fix human nature. There was clearly some kind of neurological link between building buildings, fixing pipes, and bribery, and there was nothing they could do to change that.

“It is what it is, man,” says Byron at the end of MacFarquhar’s article, and it’s hard to disagree with him. But it also seems that street food is a fascinating place to start unpacking the ways regulations, enforcement, incentives, economic development, and consumer demand interact to shape cities and their food systems.

IMAGE: Discussing food trucks during the Zoning Diet panel at Foodprint Toronto. (L-R) Nicola Twilley, Pat Pessotto, Jessica Duffin Wolfe, Barbara Emanuel, and Lola Sheppard. Photo by Stacy Lewis.

[NOTE: Tracing the ways food and cities shape each other and the hidden economic, regulatory, and cultural forces that consciously or accidentally design urban food systems is at the heart of the Foodprint Project, an international event series that I co-curate with Sarah Rich. You can watch both Zoning Diet panels online (NYC and Toronto) for more of these kinds of discussions. And please consider supporting the Foodprint Project Kickstarter campaign, as we fundraise to cover expenses from Foodprint Toronto and put together future Foodprint Project events — it could be your city next!]