Just a quick note to say that this week I’m hosting an online Glass House Conversation on the topic of food design. My question — which is open to anybody who wants to respond — is about how we should invest in food design R&D, in order to make sure we take advantage of the opportunities that redesigning food can offer, while avoiding the pitfalls. What funding structures would help make sure that food design innovation is carried out in the pursuit of social and environmental goals, rather than simply an increased bottom line? Or, as I asked over at the Glass House Conversation site:

In an era when food justice, food security, climate change, and obesity are such pressing issues, should there be public funding for food design R&D, and, if so, who should be receiving it?

IMAGE: Carrot diversity, from the Design and Assessment of Nutritionally Enhanced Carrots With Unusual Pigments, published by the USDA.

I am starting this conversation from the premise that food — the substance itself, as well as its methods of production, processing, and consumption — has always been the subject of tinkering and design. The color of carrots, the shape of silverware, and the layout of supermarkets are all products of human ingenuity applied to the business of nourishment. The application of design to food can be seen in such widely varying outcomes as Brazil’s investments in low-carbon agriculture, Natalie Jeremijenko’s cross-species eating adventures, and Monsanto’s Round-Up Ready maize.

Although several commenters disagree, I’m of the opinion that future innovations in food design offer great potential benefits, as well as dystopian “Frankenfood” scenarios. And condemning the intentional application of design to food out of hand ignores the collaborative process of domestication and evolution that, for example, morphed the same wild mustard ancestor into the vegetables we know today as cauliflower, broccoli, cabbage, and kale.

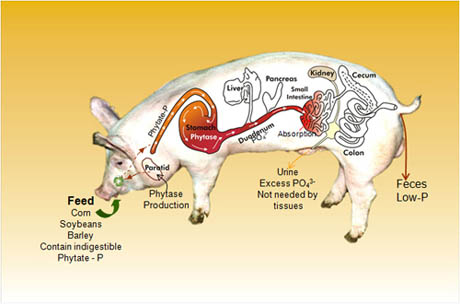

IMAGE: Model of the “Enviropig,” a Canadian-designed transgenic pig that produces manure with lower levels of polluting phosphorus, via the University of Guelph.

One of the interesting threads that emerged early on the debate is a need to define “food design,” and even break it down into different types, in order to have a productive conversation about what sorts of “food design” we might want to encourage and, conversely, which initiatives should be better regulated, or abandoned outright.

Adam Lerner, Director of the Denver Museum of Contemporary Art, even made a fascinating distinction between “food design” as an “active term” that “helps people think about how they might act to improve their world in relation to food,” as opposed to “food wellness,” which he suggested:

might be a better term when speaking about public funding and R&D. Whatever term it is, it would have to speak to a broader audience [than “food design”] and engage in the discourse of social welfare.

IMAGE: From Local Code by Nicholas de Monchaux et al.; a proposal that uses geospatial mapping tools to identify pockets of abandoned public land throughout American cities, so that they can be used for soil and storm-water remediation, as well as victory gardens and public green space.

To give some context to the conversation, I’ve also been asking people who come at food design from a variety of different backgrounds to share their thoughts about its potential, as well as their opinion on how we might best ensure it achieves that potential. I’m publishing these mini-Q&As over at GOOD.

Yesterday, for example, Paola Antonelli helpfully broke down food design into three scales: the molecular, the unit of food itself, and the systemic, with different opportunities and challenges at each level. This morning, I linked a video presentation by artist-entrepreneur Marije Vogelzang, who is careful to describe her work as “eating design,” rather than food design. I have three or four more of these short interviews or profiles to come over the next couple of days, so please check back.

Meanwhile, you have until Friday at 8:00 p.m. EST to add your thoughts to the Glass House Conversation. What areas of food design do you think should be prioritised, and how should we go about doing that? Is it best left to entrepreneurs, multi-nationals, and market forces? What are our powers as citizens, as well as as consumers? Should government intervention in food design be limited to regulation, or might it also be worth incentivising or funding research into neglected but promising areas? Jump in!