IMAGE: Mossman Sugar Mill. All mill photos by the author.

Last month, BLDGBLOG and I joined a small group (consisting mostly of wheat farmers on a busman’s holiday) to visit Mossman mill, which is just up the road from Cairns.

As it happens, we are apparently on the brink of a sugar crisis, with the Wall Street Journal reporting that Americans might face an autumn without sugar (“Can you imagine an America with no sugar? demanded comedian Stephen Colbert in response. “Juice would contain nothing but 10% juice!”)

On this apocalyptic note, then, below are a couple of highlights from our tour through Australia’s northernmost sugar mill.

IMAGE: Stage 1: Emptying billets of sugar cane into the shredder, which ruptures the cane’s cells to release the juice.

IMAGE: Each canetainer’s contents are processed separately until its sweetness level can be measured, so that the grower’s payment can be calculated correctly.

The milling process appears to begin once the canetainers are emptied into the shredder – but, in fact, the mill’s influence extends far beyond its gates, to impose a rigorous policy of sunshine equality across the entire growing region.

The rationale behind this ambitious program of solar rationing lies in the fact that the amount a farmer is paid for their sugar cane is determined by this simple equation: tonnage multiplied by sweetness. Tonnage can be increased by the usual agricultural means – fertiliser, irrigation, breeding more productive varietals, or simply sowing a larger acreage – but the most effective way to increase sweetness levels is simply to allow the cane crop more time in the sun.

The problem is that sugar cane is a highly perishable crop that needs to be processed within eighteen hours of harvest; harvest can only take place during the dry season; Mossman mill can only crush 350 tons per hour; and last year, the region produced 792,000 tons of raw cane.

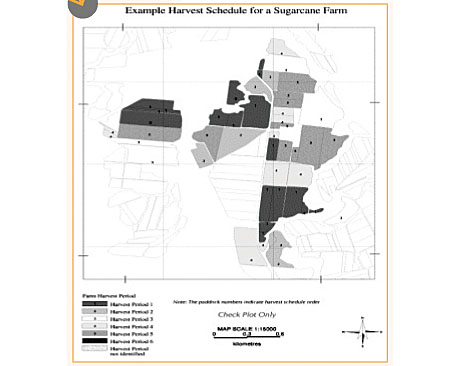

As a result, nearly a fifth of the sugar cane crop has to be harvested as early as June – missing out on four whole months of sunshine. Unsurprisingly, few farmers volunteer to go first; hence the need for the mill to institute its own sunshine equalisation system. The HarvSched database combines cane type, age, and projected yield with mill capacity in order to generate a five-month-long harvesting schedule of scrupulous fairness and optimal productivity.

IMAGE: Sample HarvSched-generated solar equalisation plan.

Each farmer’s land is divided up into dozens of smaller chunks, each of which is then given its own unique harvest date. Following the HarvSched plan means that the mill receives a steady supply of sugar through the season, the farmers receive an equal dosage of sunshine relative to acreage, and the harvesting crews enjoy a regular and refreshing change of scene.

This idea of scientifically allocating sunshine seems parodically Soviet – both heroically rational and intrinsically absurd. It would make the perfect plot device for a Viktor Pelevin short story: an electromechanical engineer embarks on a quixotic mission to achieve total solar equality across the vast collectivised farms of the USSR, eventually replacing the unreliable original star with a monumental array of mono-frequency lamps and parabolic mirrors.

IMAGE: Olafur Eliasson’s Weather Project (2003), Tate Modern, via Infranet Lab.

Elsewhere at Mossman mill, scientists are at work altering the chemistry of sugar itself.

Last year, for example, food scientist Dr. Barry Kitchen managed to lower the GI, or glycaemic index, of sugar to 50. For those who aren’t South Beach Diet veterans, GI is a measure of how quickly carbohydrates release glucose into the bloodstream during digestion. High GI foods (70+ on a scale of 100) release glucose quickly, leading to blood sugar spikes, which aren’t good, especially for diabetics.

Ordinary sugar is actually only a medium GI food (65, the same as rice and sweet potatoes), but by adding more of the polyphenols, minerals, and organic acids found in molasses back into the sugar at the centrifuge stage, Dr. Kitchen managed to produce LoGicane, the world’s first low GI sugar.

IMAGES: Freshly-harvested cane being processed into cane syrup at Mossman mill.

The process was only perfected in time for the last three weeks of the 2008 crush, producing just 600 tons of this new version of sugar. That was enough to launch in the Australian market, and it’s been sufficiently popular that the Mossman mill was producing sacks of it during my visit – our sample looked and tasted like demerara.

As a next step, Dr. Kitchen and his team in the Horizon Science Shed at Mossman are also planning to use molasses to cure obesity. Incredibly, their website claims that:

Horizon Science has identified a range of phytochemicals in molasses capable of positively changing body composition. The range of molasses phytochemicals has never been previously identified because of the focus in sugar processing to produce pure white sucrose products.

When fed to animals on a high fat diet, our molasses extract has been shown to significantly reduce body fat and increase lean muscle mass.

In an alarmingly perfect inversion, it seems as though the part of sugar cane that we usually discard in processing actually reduces body fat and promotes lean muscle mass; the part we keep makes us fat and sick.

IMAGE: Sugar crystals are separated out from the molasses in which they are suspended through centrifugal force. Typically the mixture, called massecuite, is run through the centrifuge three times – but that number can go up or down depending who the sugar is destined for. The Japanese prefer a little more molasses in their raw sugar (no doubt to bring the taste closer to their traditional wasanbon with its honey and butter overtones) compared to the South Koreans and Malaysians. Together, the three countries import the bulk of Australia’s raw sugar production each year.

IMAGE: Mossman mill

The slightly Heath Robinson, steam-era appearance of Mossman mill belies the intense innovation underway in sugar cane agriculture and processing. Indeed, the Australian government has committed to investing AUS $28 million in sugar industry research over the next seven years, citing sugarcane as “the ideal biofactory – one of nature’s most efficient converters of sunlight and water into biomass.”

Current projects range from “shoot architecture modification to boost cane and sugar yields” to genetic alterations designed “to give sugarcane the ability to express alternative, marketable products” – particularly biofuels and bioplastics (pdf).

IMAGE: QUT waterproof paper developed with sugar cane waste, with its inventors (L-R) Dr Les Edye, Dr Bill Doherty, and Dr Peter Twine, CRC CEO.

We were touring a century-old factory for reducing cane into sugar – but the sugarcane itself is the factory of the future.