In the opening episode of the BBC’s new three-part series, “Inside the Factory: How Our Favourite Foods Are Made,” we spend an hour watching a loaf of supermarket sliced white get made.

There is a short diversion into the history of bread-making (including Victorian-era DIY tests for alum adulteration) and a brief interlude in an oak forest to sample some wild yeast, but the star of the show is the factory itself: the mesmerising, balletic, perpetual motion machine installed beneath Allied Bakeries’ unpromising, West Bromwich-based, hangar-style shed.

First, the ingredients are rounded up. There is a stock shot of a combine harvester at work, but the real action takes place at the flour mill and yeast bioreactor. At Coronet Mill in Manchester, kernels of wheat loop through six miles of pipe, from mill to sieve, to mill to sieve, and around again, until they are reduced to dust.

IMAGE: Six miles of pipe transport whole kernels, milled wheat, and flour around the ten-storey mill. Screen grab from the BBC.

The sieves themselves look like a series of self-storage lockers mounted on a seismic shake table. Rows of off-white boxes punctuated at regular intervals with green doors wiggle and bounce, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week.

IMAGE: Sieves. Screen grab from the BBC.

Meanwhile, in Suffolk, six gigantic bioreactors turn 0.1 gram of yeast into 30,000 kilos (enough for 1.2 million loaves of bread) in just four days, before spraying, squeezing, and dehydrating it.

IMAGE: The yeast factory’s bioreactors. Screen grab from the BBC.

IMAGE: Extruded and dried bakers’ yeast. Screen grab from the BBC.

Tankers bring the highly combustible flour, living yeast, and a variety of other emulsifiers and additives to West Bromwich, and then the supermarket loaf’s twenty-four hour journey from flour to shelf begins.

Only three and a half hours of that are required to knead, proof, bake, slice, and bag the bread; the rest is allocated to sorting, loading, and delivery. During that three and a half hours, the bread never stops moving.

IMAGE: Dough balls “rest” for thirty-seconds for the gluten to form. Screen grab from the BBC.

Even the thirty-second “relaxation” period required between kneading and proving the dough takes place on a series of otherwise unnecessary conveyor belt loops. This is building as circulation: a gluten-based Epcot ride and mesmerizing Chris Burden installation rolled into one.

IMAGE: Proving dough. Screen grab from the BBC.

While a giant ferris wheel takes the loaves for a spin, muffins are funneled down Carsten Höller-worthy slides and into a series of race-track start gates.

IMAGE: The slide slows and separates the muffins for the quality control inspector. Screen grab from the BBC.

IMAGE: On your marks: the muffins head out onto the packaging track. Screen grab from the BBC.

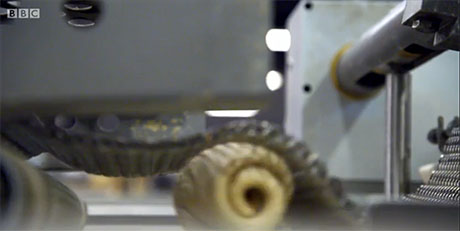

Thus far, the process at least resembles a mechanical interpretation of home bread-baking, albeit using double the ingredients and a fraction of the time. But there is a secret to supermarket bread’s combination of squishiness and spreadability: a deft series of moves that rolls up the dough ball like a cigar, cuts it into four, and then squeezes it back together again in the tin.

IMAGE: The bread dough is rolled like a cigar. Screen grab from the BBC.

IMAGE: This machine then slices and folds it in two, and then in two again, before funneling it back together. Screen grab from the BBC.

IMAGE: The four dough cylinders, lined up so that their grain alternates. Screen grab from the BBC.

IMAGE: And then dropped in the tin, to reform into a single loaf. Screen grab from the BBC.

As the bread proves and bakes, the four cylinders become one again—but, because the grain of the dough flows in alternating directions, the resulting loaf is much less likely to tear under your butter knife.

IMAGE: The loaf on the left was not divided into four; the loaf on the right was. Screen grab from the BBC.

After a trip through the room-sized oven, the bread must be cooled to below 30°C, in order to be sliced and bagged. This is “the one bit of the process we can’t speed up,” Allied Bakeries’ manager complains. Over the course of two hours, the loaves slowly circulate up to the top of a multi-storey fridge and then wind their way down the other side.

IMAGE: Spiraling up the cooling tower. Screen grab from the BBC.

IMAGE: Two spirals in the cooling tower. Screen grab from the BBC.

After a trip through the slicer*, an ingenious blow-and-scoop motion inflates a plastic bag in time to catch the loaf as it falls from one conveyor belt to another.

IMAGE: Bagging the bread. Screen grab from the BBC.

And, with a final pass through the metal detector, the loaf’s journey grinds to a temporary halt. At some point in the next twenty hours, supermarket orders will come in, and pickers will load it onto a pallet, and then a lorry. From there, it goes from supermarket shelf to basket, to stomach—or, as the show’s presenters pointed out, the bin. (British shoppers throw away the equivalent of one out of every three loaves purchased.)

The episode is still available on iPlayer, as are the subsequent programmes in the series, on milk and chocolate. It’s the kind of food television I love—and that is vanishingly rare. Although the presenters point out the differences between industrial processes and home baking and the unnecessary nature of much food waste, there is no agenda other than curiosity. Most of us—even those of us that write and think about food almost constantly, like me—will never have seen the inside of commercial bakery, let alone the yeast bioreactors and flour mills that feed it. And it is a fascinating, awe-inspiring, and occasionally revelatory sight.

*As designer and food historian Cory Bernat once pointed out, sliced bread wasn’t really the greatest thing until cellophane came along to keep it fresh. Although Iowan Otto Rohwedder designed his “single-step bread slicing machine” in the 1920s, when the first pre-sliced loaf was sold on July 7, 1928, it was wrapped in wax paper, which was far from air-tight, as well as difficult to reseal. Fortunately, DuPont came out with the first impermeable plastic wrapping in 1927, and by the early 1930s, sliced bread was being sold in cellophane. “Cellophane on bread! Impossible, one might say, but it’s a fact,” reported the Sarasota Herald-Tribune in 1934.

For another look at food manufacturing’s industrial sublime, see “In the Time of Full Mechanisation.”

Thanks for the tip, Mum!