IMAGE: The Green Barrier at Hassi Bahbah, Algeria, via.

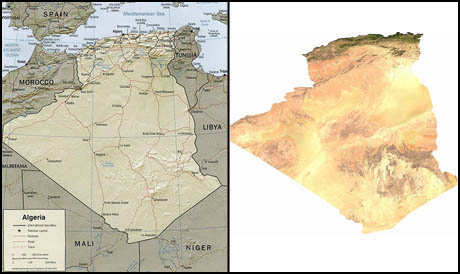

Algeria is not a small country – according to Wikipedia, it is one hundred three-and-a-half times the size of Texas – but eighty-five percent of its territory consists of the Sahara desert. In fact, only a thin strip of land along the northern coastal edge of the country is cultivable.

IMAGE: Relief and satellite maps of Algeria, via Wikipedia.

In the 1970s, determined not to let the Sahara encroach further onto its thin sliver of agriculturally useful land, Algeria embarked on a sort of steampunk geoengineering project: planting a wall of trees up to 16 miles wide and 746 miles long along the entire length of the Sahara’s northern edge, from the Moroccan to the Tunisian border. Three hundred and ninety-five thousand acres of the Green Barrier, or barrage vert, were planted between 1974 and 1981, mostly by young men as part of their military service.

IMAGE: The Green Barrier as seen from ground level, via.

After this initial burst of activity, the Green Barrier ran into various economic, sociological, and ecological issues. The Barrier was a monoculture, entirely planted with the hardy, heat- and drought-tolerant Aleppo pine, which was a fine idea until the pine processionary moth moved in. Meanwhile, the funding ran out, and the local population, who hadn’t been included in the project’s planning or planting phases, saw the trees as a handy source of building materials and firewood. By 2007, the Sahara had migrated to within 125 miles of the Mediterranean, while the remains of the Barrier were described as “a depressing sight […] more grey than green.”

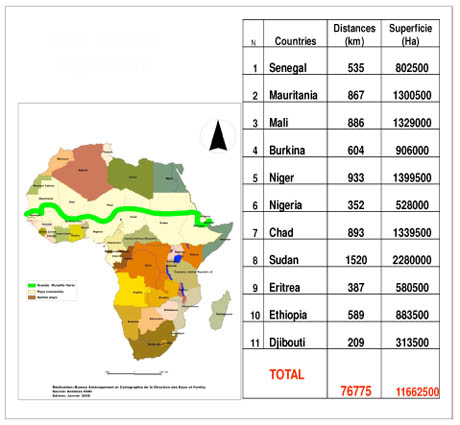

Nonetheless, during this month’s equally depressing Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen, Senegalese officials told National Geographic that 326 miles of a second Great Green Wall had already been planted. The idea was proposed in 2005 by the former Nigerian President, Olusegun Obasanjo, and formally adopted by the African Union in 2007.

If it is completed as planned, this vast agro-ecological defensive landscape will ultimately be 9.3 miles wide and 4350 miles long, crossing through eleven countries from Dakar to Djibouti.

IMAGE: The route of the proposed Great Green Wall.

Although this second green wall is also being built by soldiers (on loan from France), the team behind it do seem to be considering a wider range of vegetation, as well as ways to integrate the Great Green Wall into the lives and economy of local population. By including the native Acacia senegal in the plantings, for example, scientists hope that farmers will eventually be able to profit by harvesting the sap, which is better known as gum arabic, a key ingredient in soft drink syrups, confectionary, and cosmetics.

Meanwhile, the jury is still out as to whether ribbons of forest can actually hold back the encroaching sand. For example, the results of China’s own Green Wall project, which began in 1978 and is expected to reach the end of its fourth phase in 2010, have been pretty varied.

Most scientists agree that Africa’s Great Green Wall is not enough on its own, and that developing less-pasture intensive breeds of livestock, researching and implementing dry agriculture techniques, educating local farmers, improving water conservation and soil management, and reducing firewood-dependence among rural populations are equally – if not more – effective strategies against desertification.

IMAGE: Sunrise during the 2009 Great Sydney Dust Storm. Photo by Tim Wimborne/Reuters, via The Guardian.

Nonetheless, with desertification on the rise and the resulting dust storms being blamed for atmospheric pollution, glacial melt, harvest failures, and even the spread of infectious diseases, quarantining the deserts of the world behind ringed walls of carbon-absorbing artificial forests might not be such a bad idea.

NOTE: For a more ingenious Saharan wall proposal, which involves turning sand into sandstone by injecting it with bacillus pasteurii, check out Magnus Larsson’s Dune on BLDGBLOG, or watch his recent TED talk.