Matthew Spremulli, an architecture student at the University of Toronto, has recently embarked on an ambitious, if potentially quixotic, project: the assembly of an Agri-Tech Catalogue.

IMAGE: The rake, from Matthew Spremulli’s Agri-Tech Catalogue (click for larger image).

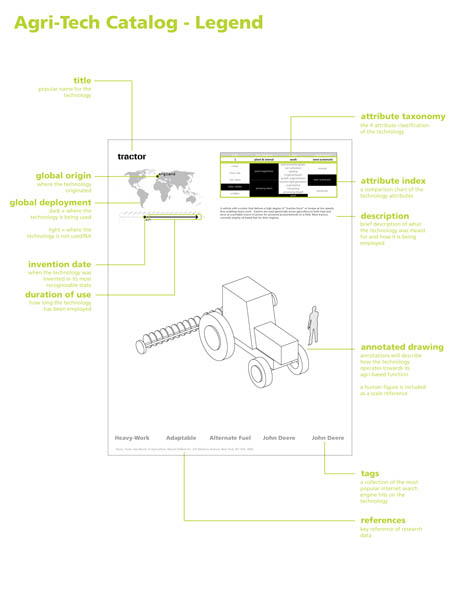

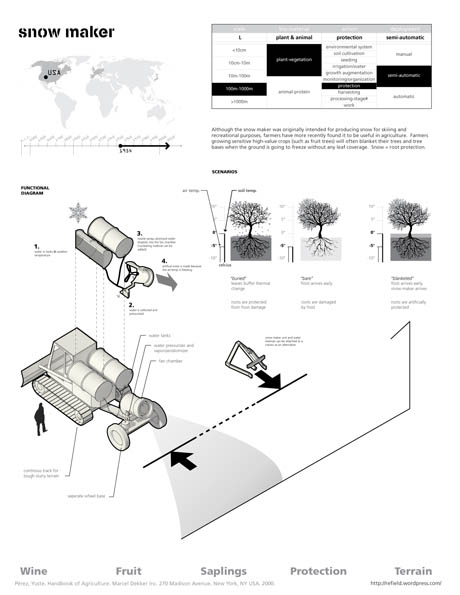

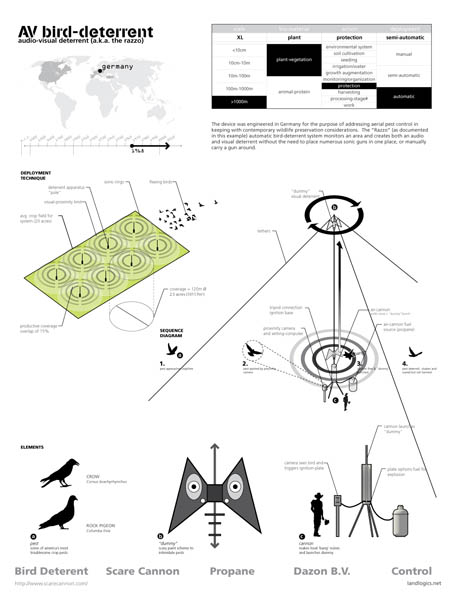

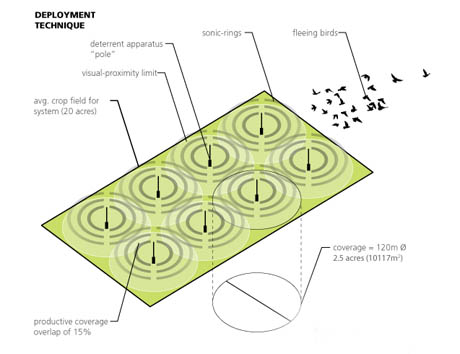

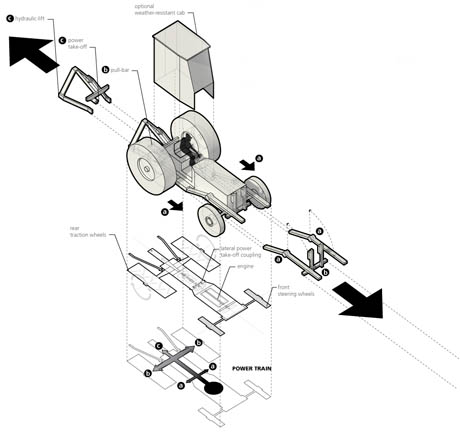

Thus far, his nascent encyclopedia of food production technologies contains the rake, the tractor, the self-propelled sprayer, the AV bird deterrent, and the snow-maker. Each individual device inhabits a single page of his future catalogue, complete with an annotated drawing and several different classification data points, including its invention date, type of action, and a list of tags drawn from the most popular accompanying search engine terms.

IMAGE: Proposed format for the Agri-Tech Catalogue (click for larger image).

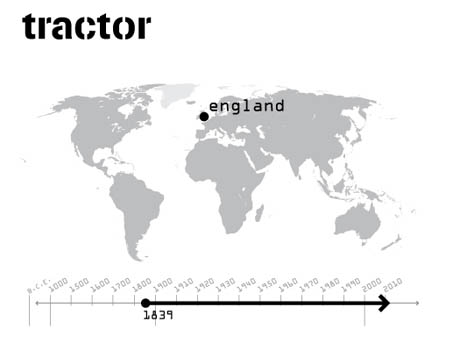

We thus learn that for the majority of English-language internet users, the rake goes hand-in-hand with thoughts of “grubbing,” “sales,” “patent,” “tool,” and the “Midwest.” The tractor, on the other hand, is associated with “John Deere,” but also with questions of “alternate fuel,” “parts,” “pulling,” and “use-reuse.”

IMAGE: Detail from the tractor page in the Agri-Tech Catalogue (click for larger image).

IMAGE: Detail from the tractor page in the Agri-Tech Catalogue (click for larger image).

Other metrics include the scale over which the technology is typically deployed. The self-propelled sprayer, for example, is commonly used at a scale greater than 1000m², while the rake is more frequently used over areas sized between 10cm² and 10m².

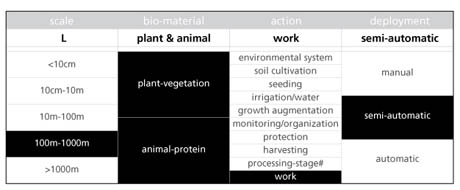

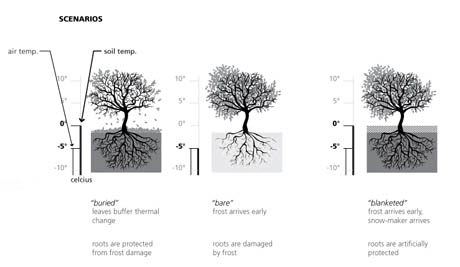

Accompanying maps and timelines show that the bird deterrent was invented in Germany in 1968, and is used in the U.S., Canada, Turkey, as well as much of continental Europe, and that the snow-maker was invented for recreational purposes in the U.S., but is now used in agriculture to create a protective blanket around frost-sensitive crops in Japan, the U.K., and continental Europe with the curious exception of Portugal.

IMAGE: Snow-maker, from the Agri-Tech Catalogue (click for larger image).

IMAGE: Detail from the snow-maker page in the Agri-Tech Catalogue.

I find this kind of obsessive collection, annotation, and categorisation utterly irresistible. Like Diderot’s original Encyclopédie, it is a machine de guerre — a technology in and of itself, used to stake out the form and meaning of a particular branch of knowledge, while simultaneously opening it up for redesign and expansion. It offers the tempting illusion of complete understanding, as well as opening genuine possibilities for discovery and improvement.

Already, at this early stage in Spremulli’s endeavour, we can see a logic of agricultural technologies begin to emerge, as well as a guide to sites of possible intervention.

IMAGE: AV bird deterrent, from the Agri-Tech Catalogue (click for larger image).

Take the AV bird deterrent (or razzo): it automates the role of a farmer protecting his crops armed with a gun and assorted scarecrow simulacra — yet the plants only require protection because early humans domesticated grains by selecting for vulnerability, breeding out toxins and thorns.

In other words, the razzo is a plant prosthesis, restoring lost capabilities, as much as it is a robot farmer. Meanwhile, the technology itself creates new environment realities through the precise geometry of its visual proximity radii (60m) and sonic rings.

IMAGE: Detail of the AV bird deterrent from the Agri-Tech Catalogue.

Perhaps most excitingly, if these tools are both cause and symptom of agricultural man’s relationship with the land, then they also offer a ready-made modular infrastructure, just waiting to be hijacked in order to redesign that relationship.

In particular, Spremulli points out the potential of the power take-off (PTO) on tractors, which is a rotating driveshaft that can be used to power an attachment or a separate machine. Because the PTO conforms to ISO standard speed and dimensions, every single modern tractor, everywhere in the world, could easily run any new implement.

IMAGE: Detail from the tractor page in the Agri-Tech Catalogue (click for larger image).

This, notes Spremulli, “could be quite an opportunity for rethinking our current agricultural practice.”

In addition to the opportunities for artists to create “experience machines” — tractor-powered rainbow makers or musical instruments — Spremulli suggests that ecologists design remediative PTO attachments. These speculative parasite devices could be cheaply mass-produced and distributed to farmers around the world, ready to slot into the iconic technology of industrial agriculture and subvert its logic by rehabilitating depleted ecosystems, promoting biodiversity, and reversing erosion.

IMAGE: From Rainbow Maker’s World, an artificial rainbow over the UN in New York.

As Spremulli’s Agri-Tech Catalogue grows, I expect to see many more design opportunities like this emerge: you can follow his work online at the landlogics blog, written in collaboration with fellow Daniels student Fei-Ling Tseng.

[NOTE: Be sure to check out Spremulli’s guest post, Corn Belt 2.0: Synching the Starchscape, at the Infranet Lab blog, where I first came across his work.]

Discover more from Edible Geography

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.