J. Crew’s La Boucherie boxer shorts illustrate French cuts of meat such as the poetically named faux-filet, tendron, and bavette d’aloyau, via Eat Me Daily.

I first saw sot l’y laisse on a restaurant menu as a teenager, somewhere in south west France. I risked appearing the fool by asking the waiter what on earth they were, and even though I couldn’t quite follow his explanation, ordered them rather than make matters worse.

It wasn’t until we were safely home in suburban Surrey and Dad was dismantling the remains of the Sunday roast that Mum and I thought to investigate. When we did indeed find the sot l’y laisse, one tucked in either side of the chicken’s backbone, it felt like discovering a secret compartment or buried treasure.

As it turns out, chefs frequently cite the sot l’y laisse, or oyster as it’s called in English, as their favourite part of the chicken. “It can be sublime,” concurs the New York Times’ Mark Bittman.

Bill Roenigk, vice president of the National Chicken Council, offers an intriguing explanation for the oyster’s appeal – something to do with being dark meat that is nonetheless used purely as chicken architecture, rather than for any muscular purpose. However, I suspect that for most chefs, the real charm of the chicken oyster is the novelty: they are still cooking and serving chicken, but in a weird new shape that the majority of their customers will never have seen.

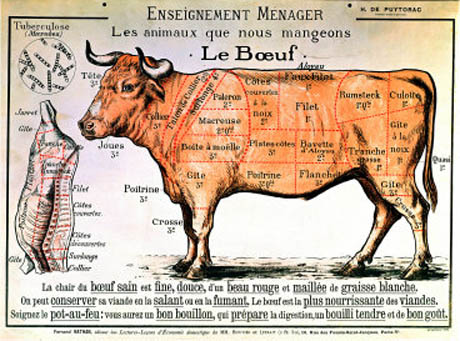

Compare French cuts of beef (described on this website) with their American counterparts (outlined on this pdf) to see traditional alternative meat forms.

Of course, as any meat-eater who has moved country (or even from coast to coast in the US) knows, the shape your beef or lamb can take varies according to local butchery techniques. Processing a carcass becomes an interpretive act; the cuts butchers make determine what forms and units are culturally recognisable as meat.

These deeply ingrained traditions make alternative cuts practically invisible – secret forms hidden within an animal’s carcass. Leaving consumer preferences and waste issues aside, it’s hard not to wonder what fantastically shaped pieces of beef lie beneath a cow’s hide, awaiting their Michelangelo: “I saw the paleron in the beef and carved until I set it free.”

And, on that note, the U.S. Cattlemen’s Beef Board and National Cattlemen’s Beef Association have embraced the creative potential of butchery with the launch of BAM: Beef Alternative Merchandising. As meat scientist, Dr. Chris Raines (Assistant Professor at Penn State University in the Department of Dairy & Animal Science) explains:

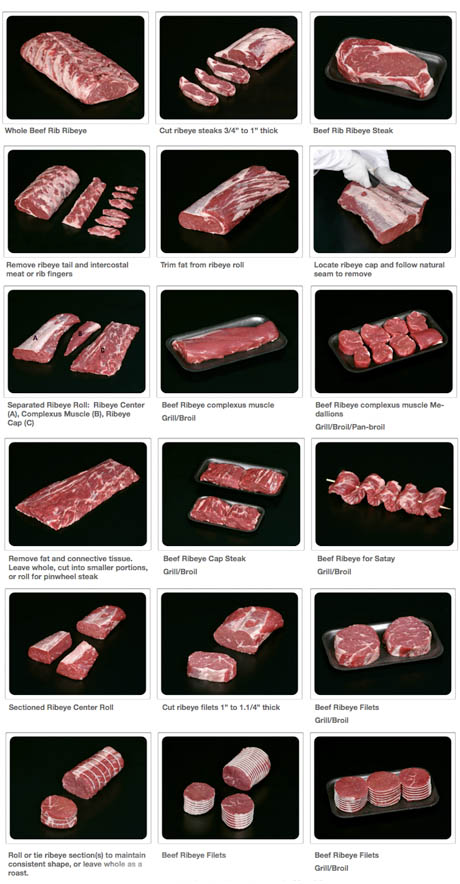

Beef has been fabricated the same general way for decades, and during that time, the cattle we produce have changed. They are larger, leaner. Ribeye and strip steaks have gotten bigger, and subsequently, so have portion sizes of these traditionally high-value beef cuts. A single steak can represent 4 to 5 servings of beef (1 serving of beef = 3 oz.).

BAM proposes a set of alternative cutting methods that creates smaller, fillet-like steaks from the sirloin, rib, and short loin. The website provides pioneering butchers who want to offer their customers “such innovative selections” with a set of point-of-sale materials and recipe cards, as well as bullet-pointed patter. Take the Beef Ribeye Cap Steak Boneless: “cut from the third most tender muscle,” it’s tender, tasty, and versatile – “think upscale fajitas.”

BAM Ribeye flashcard produced by the Cattlemen’s Beef Board and National Cattlemen’s Beef Association. Traditional Merchandising: Beef Rib Ribeye Steak =>Beef Alternative Merchandising: Beef Ribeye (complexus muscle), Beef Ribeye Cap Steak, Beef Ribeye Filet, Beef Ribeye Petite Roast.

At Beef Boot Camp, butchers were trained on the new cuts; according to Raines, “You could watch the longtime meat cutters shudder and hear them gasp as the sharp knife split the top loin half-in-two (lengthwise).”

And so with one slice, a new form of beef is revealed. It’s “value-added fabrication” for meat, or the sculptural discovery of secret shapes within the familiar architecture of an animal.

3 Comments

I thought of this while reading about a 200,000-year old carcass that apparently reveals early butchering habits.

It’s by no means the most interesting article in the world, but the discovery of this thing seems to provide “new clues about how, where and when our communal habits of butchering meat developed, and they’re changing the way anthropologists, zoologists and archaeologists think about our evolutionary development, economics and social behaviors through the millennia.”

The point is basically that you can extrapolate larger, archaeologically invisible social formations from the style of cuts found on the animal bones…

Ahem.

I should explain my exclamation: I spent some time a while back on a forum on which the readers collected a whole bunch of “diagrams of meat”, along with various images which used the conventions of the butcher’s meat diagram in their conception. I had forgotten all about this – admittedly rather strange – collection, until I encountered the author’s work on Bldgblog and above. It was sadly lost with the passing of the forum, but I suspect a grand collection of meat diagrams is simply waiting to be collated.

Diagrams of meat!