Earlier this year, Sarah Lohman of the historical gastronomy blog Four Pounds Flour and Jonathan Soma of the Brooklyn Brainery launched a monthly “bar room lecture series” on food called “Masters of Social Gastronomy” (MSG for short). Although other commitments kept me from attending their inaugural lecture on strange meat (including bear, rotten shark, and moose “mouffle”), as well as February’s presentation on sweets, which covered gold-flecked Manus Christi lozenges (taken like a vitamin by Henry VIII) and the science behind xylitol’s mouth-cooling effect, I consoled myself with the thought that they probably weren’t as interesting as I imagined them to be.

IMAGE: Manus Christi, via Alysten’s blog, where you can also find a recipe.

However, if March’s MSG lecture on artificial and natural flavouring was anything to go by, I was probably wrong. From Herodotus’ description of the cinnamalogus, a mythical bird whose nest is made of cinnamon sticks, to the delicious Concord grape smell and wart-removing powers of methyl anthranilate, Soma and Lohman took their audience on a surprising, instructive, and extremely entertaining journey to sound out the shifting categories of “natural” and “artificial” as they apply to the equally murky territory of food flavourings.

IMAGE: The Cinnamologus bird, shown in a medieval bestiary belonging to the Museum Meermanno.

As Lohman pointed out, humans have been adding substances to food to enhance or change its flavour for thousands of years. For example, a millennium before sugar reached Europe, the Romans developed their own artificial sweetener with preservative qualities called defrutum, which they added liberally to wine, fruit, and even meat dishes. A reduction of grape juice, boiled in lead pots to create lead acetate, defrutum consumption has superseded lead-lined viaducts as one of the leading factors in the Roman Empire’s decline, at least for some historians.

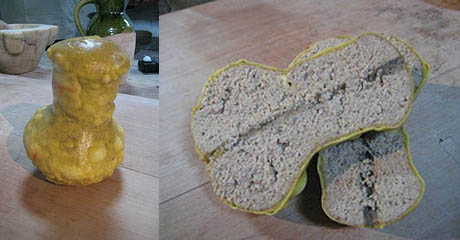

Medieval nobles, meanwhile, were famed for their appreciation of a much more literal food trickery, and their kitchens frequently spent hours sculpting and moulding foods so that they looked like other foods (for example, trayne roste, a dish of mock entrails made from battered fruits and nuts) or even resembled inedible objects, such as the meat pitcher shown below.

IMAGE: A slightly wonky homemade meat pitcher, from the blog of Hampton Court Palace’s Tudor kitchens.

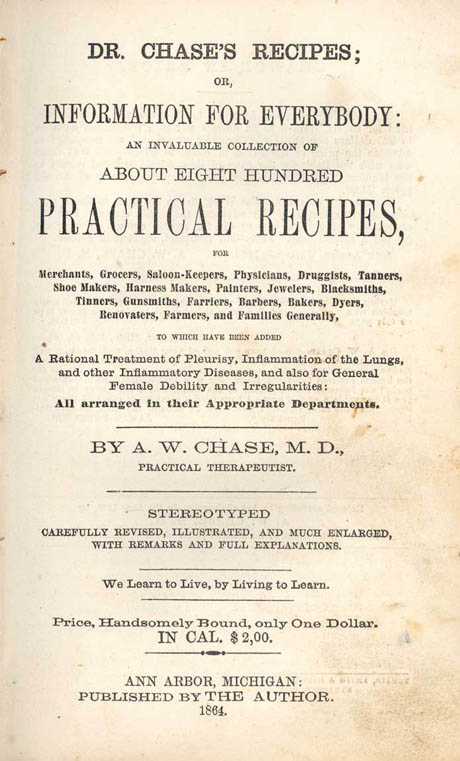

However, the first recipe for producing the flavour of a particular food by other means was apparently published in 1864, in Dr. Alvin W. Chase’s Information for Everybody: An Invaluable Collection of About Eight Hundred Practical Recipes, a compendium of tips on waxing fruit, liming eggs, and making cider without apples and “with but trifling expense.” Chase’s formula for artificial pineapple flavour calls for the same chemical used in pina colada and daiquiri mix today: ethyl butyrate.

Raspberry — Is made as follows:

Take orris root, bruised, any quantity, say ¼lb., and just handsomely cover it with dilute alcohol, (76 per cent, alcohol, and water, equal quantities,) so that it cannot be made any stronger of the root. This is called the “Saturated Tincture;” and use sufficient of this tincture to give the desired or natural taste of the raspberry, from which it cannot be distinguished.Pine Apple flavor is made by using, to suit the taste, butyrio-ether.

By this point in American history, artificial flavours were already commonplace, as Chase continues with a preemptive counter to any critics:

Others will object to using artificial flavors. Oh! they say: “I buy the genuine article.” Then, just allow me to say, don’t buy the syrups nor the extracts, for ninety-nine hundredths of them are not made from the fruit, but are artificial.

IMAGE: Dr. Chase’s recipes are available online at the Historic American Cookbook Project.

As opposed to the toxic but publicly celebrated artificial sweeteners of Rome and the self-conscious trickery of medieval feasts, the mid-nineteenth century saw the first widespread use of artificial flavours as deceptive adulterants. Rapid urbanisation in both Britain and (a little later) the United States created a new distance between food producers and consumers, and, as historian Bee Wilson has written in her excellent history of food fraud, “adulteration thrives when trade operates in large, impersonal chains.”

Eventually, public outcry over formaldehyde-laced milk, copper sulphate-green peas, and Upton Sinclair’s sausage led to government action: Britain passed the first in a series of Adulteration Acts in 1860, and, by the early twentieth century, the U.S. FDA came into being to enforce the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906.

Of course, regulation requires definition, and this is where things became (and have remained) extremely interesting, as committees of politicians, scientists, retailers, and lawyers navigate cultural assumptions, rhetorical sleigh-of-hand, and the current state of technology in an ongoing attempt to create a watertight, enforceable distinction between nature and artifice, at least in terms of food flavouring.

IMAGE: Bottled food flavourings for sale at The Baker’s Kitchen.

This is no easy task. After all, all flavourings are chemicals that are added to food to enhance or change the way it tastes, and all flavourings are also manufactured by humans (although, of course, many flavour production processes are now mechanised).

Britain’s first attempt at regulation defined artificial flavouring, or adulteration, in terms of intent to deceive: all flavouring was equal, unless it was found in food sold as pure. This had the side effect of making it almost completely unenforceable, according to Bee Wilson, as “swindlers could be convicted only if it could be proven that they personally had an intention to deceive, which was, in most cases, virtually impossible to show.”

Meanwhile, today’s multi-page definitions rely on the perceived “naturalness” of the flavouring source, as well as the particular production process employed, which creates its own challenges in the face of shifting cultural understandings of edibility, combined with technological innovation.

IMAGE: A thin-film evaporator used to make food flavourings by Frutarom.

Fortunately for the audience, Lohman had brought along some snickerdoodle cookies to help illustrate the nuances. Snickerdoodles are flavoured with vanilla and cinnamon, each of which comes with an intriguing story.

The most shocking revelation of the evening concerned cinnamon, which, in the United States, whether natural or artificial, is likely not to be cinnamon at all, scientifically speaking. “True” cinnamon flavour comes from the bark of the Cinnamomum verum tree, but the FDA has determined that the bark of the cassia tree, another member of the Cinnamomum genus, can also be sold as cinnamon.

IMAGE: True cinnamon is on the far right, cassia bark is on the far left, and in the middle is Indonesian cinnamon, which is also not true cinnamon, and which is lower in cinnamaldehyde and more expensive than cassia, but which does look nice stirring a Mexican hot chocolate. Photo via the Brooklyn Brainery blog.

Cassia has the benefits of being both cheaper and more potent (it actually contains more cinnamaldehyde, the essential oil that gives cinnamon its characteristic flavour, than its verum cousin), and has thus usurped true cinnamon’s flavour note in everything from Yankee Candles to Cinnabon. In Europe, however, only true cinnamon can be sold as cinnamon, and cassia must not only be labeled as such, but also accompanied with a health warning about the anti-coagulant effects of coumarin, one of the other flavour compounds it contains.

While cinnamon in the United States is a government-sanctioned imposter, plain old vanilla is, surprisingly enough, a relatively recent addition to the American flavourscape. In addition to Chase’s fake fruit syrups, the mid-nineteenth century saw vanilla replace rosewater in creams, jellies, puddings, cakes, pies, cookies, sodas, and more, in just a few decades. This wholesale taste takeover came about as the result of the accidental discovery, in 1842, of a method for artificially pollinating the vanilla orchid — which in turn led to natural vanilla extract becoming cheap enough to be ubiquitous.

That price has continued to drop as vanilla — America’s favourite ice-cream flavour by a significant margin — can now be made in any number of ways, some of which have stretched the boundaries of U.S. FDA definitions of “natural,” and “artificial” flavouring.

IMAGE: Vanilla beans, via.

It seems straightforward, initially: Natural vanilla flavour must be extracted from chopped up vanilla beans, usually by sitting them in ethyl alcohol for a week or more (which results in “pure” vanilla extract), although glycerin or propylene glycol (which is used to deice aircraft) can also serve as a base. Artificial vanilla flavour consists of nature-identical vanillin (the chemical that gives vanilla its characteristic flavour) that is made from something other than vanilla beans — typically wood pulp, as a by-product of the paper industry, although it can sometimes be derived from coal tar.

However, just to add a further twist, vanillin can also be made by using a particular bacteria to ferment the ferulic acid found in corn and wheat bran, and, because the FDA has determined that a flavour is “natural” if it is derived from edible sources and made using physical, microbiological, or enzymatic means analogous to a normal cooking process, this ferulic vanillin (which is chemically identical to the wood pulp and coal tar vanillin) is considered a natural flavouring — although (the FDA has ruled, after extensive consultation) it is not a natural vanilla flavour, because it doesn’t come from vanilla beans.

On the other hand, the vanillin synthesised from cow dung by Japanese scientist Mayu Yamomoto (an achievement for which he received the 2007 IgNobel Prize for Chemistry) would not be considered a natural flavour, because cow dung is not currently considered to be food, at least by humans.

IMAGE: One of the snickerdoodles — but is it all-natural or artificially flavoured? Photo via the Brooklyn Brainery blog.

As Lohman and Soma gently led us through these rather abstract points, we sampled their tangible embodiment in cookie form: Lohman had made one snickerdoodle using artificial vanillin and cassia, and one using vanilla extract and true cinnamon. Soma’s contention was that, because most of the additional compounds that add subtle extra notes to natural flavours burn off at the high temperatures required to bake cookies, paying extra for the natural extract and Ceylon cinnamon was a waste. Lohman, who had spent the entire day in the kitchen preparing the cookies, begged to differ.

In the end, the audience blind taste test proved Soma correct: by a solid two-to-one margin, Brooklyn’s cookie eaters prefer fake cinnamon and artificial vanilla. I am bizarrely proud to say that I was in the minority that liked the taste of the “naturally” flavoured cookie more; I’d speculate that that’s not due to a particularly sophisticated palate, but rather because I grew up in cassia-free England and have never developed an American love for strong cinnamon flavours.

In any case, in an era when federal courts are trying to determine whether Fritos made with genetically modified labels can still bear the label “natural,” this was a fascinating exploration of the ways in which we try to make distinctions, through taste, intention, process, and provenance, between the chemical compounds that make up our flavourscape.

If you’re in New York, you can join Lohman and Soma for the next MSG on April 24th, when the topic will be “fake meats and the history of veganism.”